Gideon Lewis-Kraus came to write about UFOs with some reluctance. Among a series of serious topics on the table for New Yorker staff writers to dig into was an odd and curiously vague request: someone should, “look into what the hell is going on with UFOs.” Lewis-Kraus remembers thinking, “I’d love to read that. I’m not sure I’d want to write it, but they should definitely do that story.”

As an experienced journalist and staff writer at The New Yorker, Gideon pushed ahead with pieces attached to the news cycle—at the time the country was focused on the end of the Presidential primaries, and locking down in the early weeks of the Covid-19 pandemic. “But then by November,” Gideon told me in a recent interview, “People were ready for some counter-programming.” And so, after the election, he and his editor revisited the UFO idea.

The result is nearly 13,000 words of meticulously reported work on ufologists, the pentagon, and skepticism. In his Reporter at Large piece “How the Pentagon Started Taking U.F.O.s Seriously,” Lewis-Kraus demonstrates an essential point of reported nonfiction: finding the right story means asking the right questions. What he creates is a story about the story—an exploration into why UFOs became the butt of the joke, and what it took to pull the topic out of the taboo.

Brandon Arvesen: Where do you even start for this kind of a story?

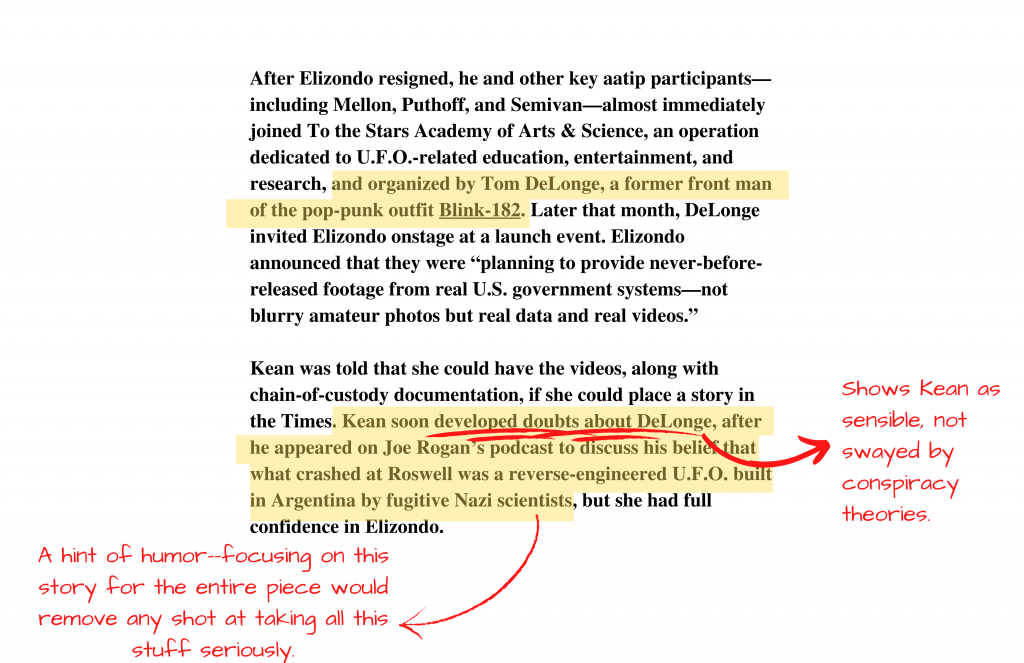

Gideon Lewis-Kraus: The first idea that I had as I was trying do it surrounding Tom DeLonge, the Blink 182 guitarist. As I started looking through it, I thought that this is a really funny story. The guy from Blink 182 has become this UFO expert and has brought together all these former military and defense industry professionals to work on this stuff. But I also realized quickly that it was going to be hard to do that version of the story seriously. That’s just fundamentally a comic story. And I thought the world does not need one more bumbling comic tour through weird UFO subculture. Not that that kind of thing can’t be done well. Stephen Rodrick did a good version of it for Rolling Stone last summer and Sarah Scoles has gone to UFO conventions and to talk to the nut jobs. And I thought that’s just not all that interesting to me.

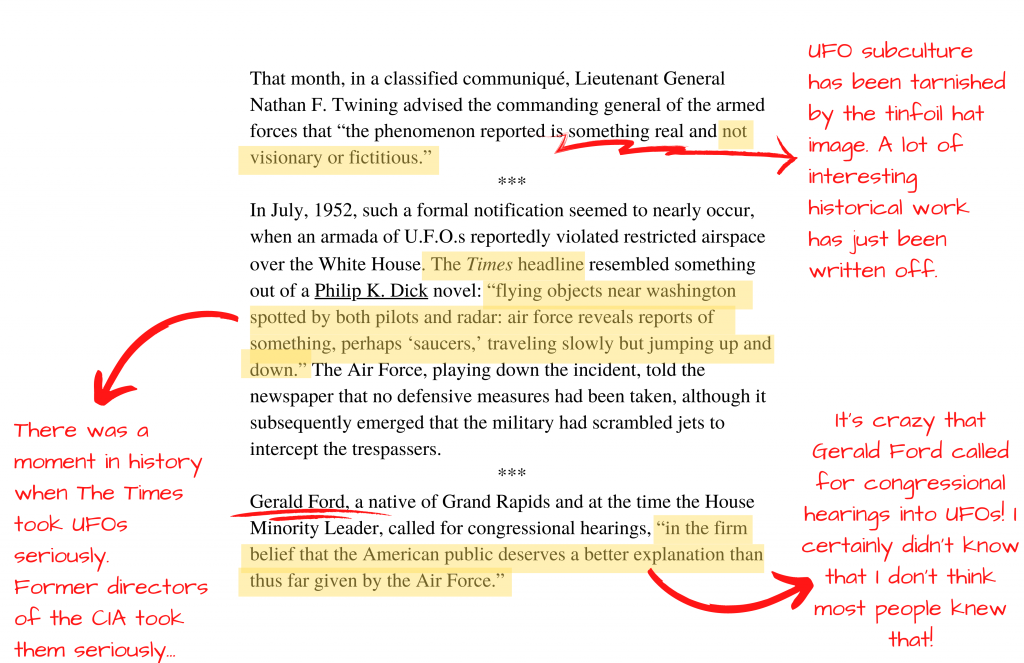

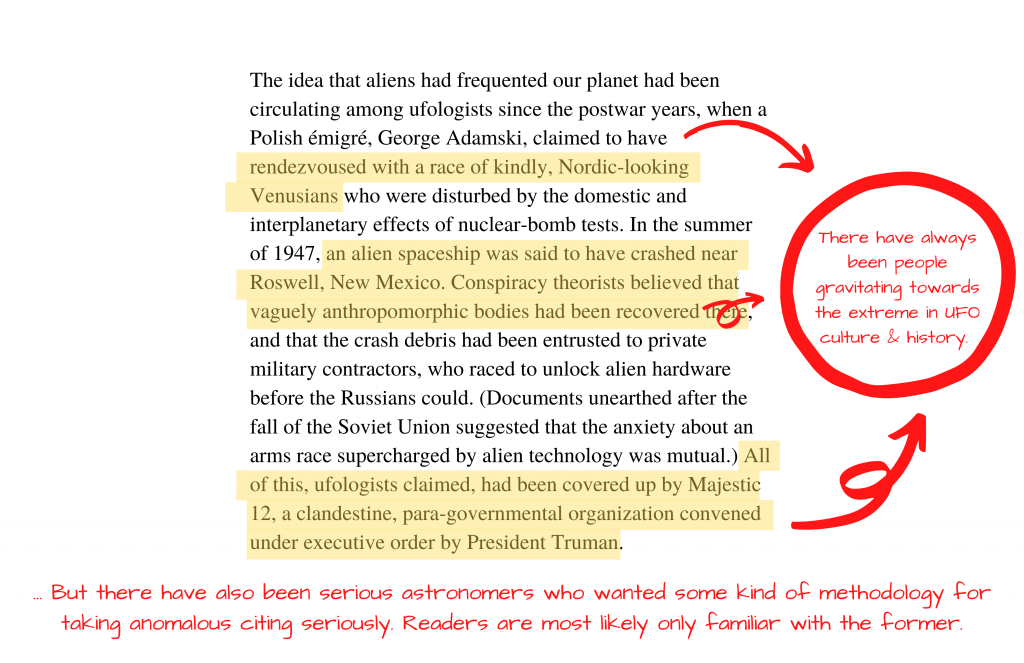

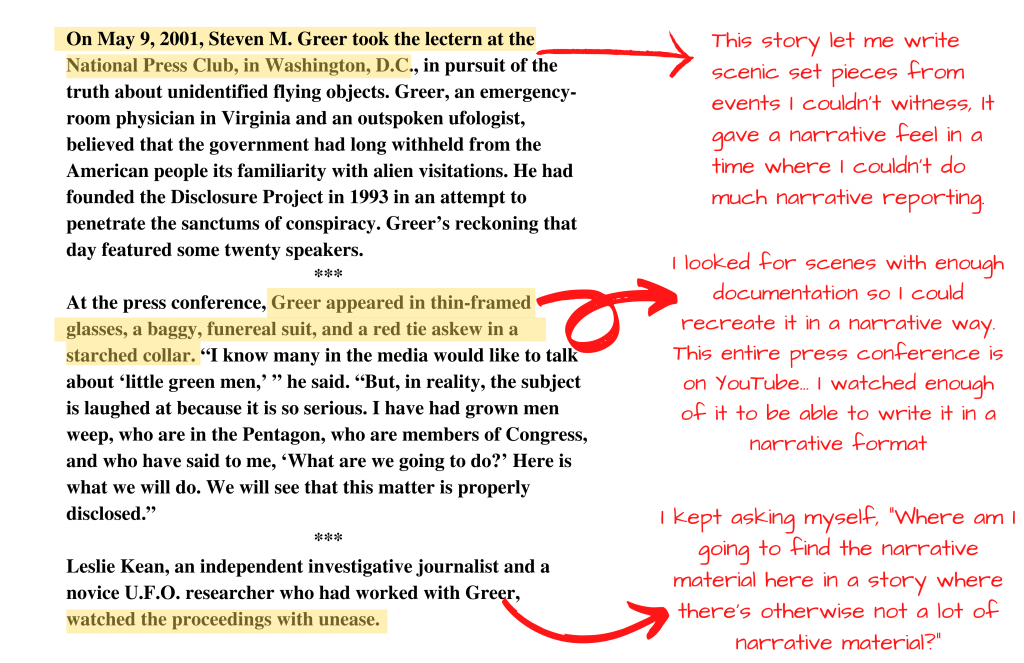

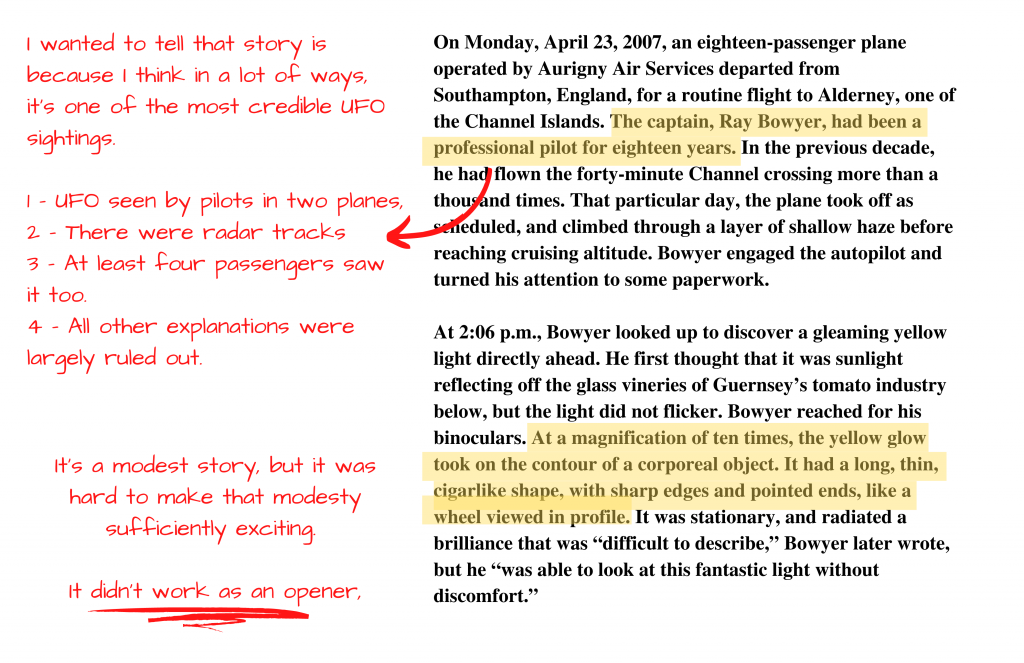

GLK: I would be interested if there were some way to take it seriously. So, I said to my editor “Let me try and figure out what a serious version of this looks like.” The first thing I did was I basically Googling, “What are the serious books about UFO’s?” And Leslie Kean’s book was overwhelmingly recommended as the most sober and careful UFO book. I read it and I thought, even setting aside the question of the reliability of some of these eyewitness encounters, just the history was totally fascinating. I had this vague sense that UFOs used to be part of popular culture, like lurid dime store paperbacks, but I really had no idea how completely seriously this had been taken by the mainstream public and even by high ranking military officers and elected officials. There was this entire lost history– lost to me. UFO people know this history really well.

BA: How did that shape your approach with reporting and writing the article?

GLK: I look at any given story as having some animating question or hypothesis that I’m setting out to answer–a question or hypothesis I’m setting out to prove or disprove. It was pretty obvious that I was not going to settle the question what UFOs are. I wasn’t going to find out if UFOs are alien spaceships? So, what is the question that I could conceivably answer here? It occurred to me that there was something to be done about the arc or the career of the UFO taboo. There was a time when the New York Times ran serious articles about an Armada of UFOs spotted over the White House in 1952. That stuff, wasn’t that rare. When I went to Leslie Kean’s house, she had this incredible archive of Life Magazine and Look Magazine and the Saturday Evening Post, and even New York Times Magazinewith cover stories about UFO’s. The idea that this taboo was essentially a feat of top-down engineering, that the senior figures in the military and the government planned to render this a disreputable topic, was true. It took them a while, but they eventually succeeded.

BA: Is that why you centralize Leslie Kean as like a main character?

GLK: So, you know, I had some reservations at the beginning because it’s always tricky to write about a journalist as a character. Ian Parker did a great Glenn Greenwald profile, There’s a famous Calvin Trillin profile of Edna Buchanan, there are lots of great journalist profiles, but, I was a little skittish about that. Leslie is just a really interesting person. She has this crazy backstory: related to Peter Stuyvesant and William Lloyd Garrison, and more recently the former governor of New Jersey. But also, she is more of an activist. So, I thought this piece wasn’t going be a profile, but in a lot of ways, she really is the one [to focus on]. She has an interesting personal story where she essentially spent twenty years banging her head against the wall, trying to get people to take UFOs seriously. And then suddenly, she discovers that while she was trying to meet with people at the White House, the secret program that she was calling for existed. And then she manages to get into the Times! So, I thought she’s not the main character in the story, but she’s an interesting part of the story. Especially the part that was a bit of media story that shows this is the power of the New York Times. That by taking this seriously, they could set this kind of president.

BA: It’s not a profile of Kean, but we spend a lot of time in her apartment with you offering set pieces and commentary. Why, take that departure if she’s not the main character?

GLK: What I really liked about her is how she defied the stereotype of what people think of as a “UFO person.” Do I think that Leslie is right about everything? No. Do I think that there are some cases that she takes more seriously than was warranted? Sure. Are there places where I think she ignores evidence that disconfirms her hypothesis? Yes. But on the whole, I found her to be this incredibly normal sensible person. To some extent there’s a little bit of a shell game that she and a lot of the UFO people play where on the one hand they say, “Look, we’re totally agnostic about what these things are. We’re not talking about alien spaceships. We’re just talking about anomalous perceptions. Maybe they’re drones or maybe they’re advanced weapons.” But then on the other hand, obviously, they think that they’re aliens spaceships. Right? I felt like Leslie did a very good job not concealing her real beliefs, but at least setting aside what clearly her personal predispositions were about this in order to take a fair look at the evidence. So, she struck me as a very useful vehicle to say here is what a person takes this seriously looks like.

BA: You present her as the normal, but are you saying through her that UFOs are going to turn back into taboo discourse?

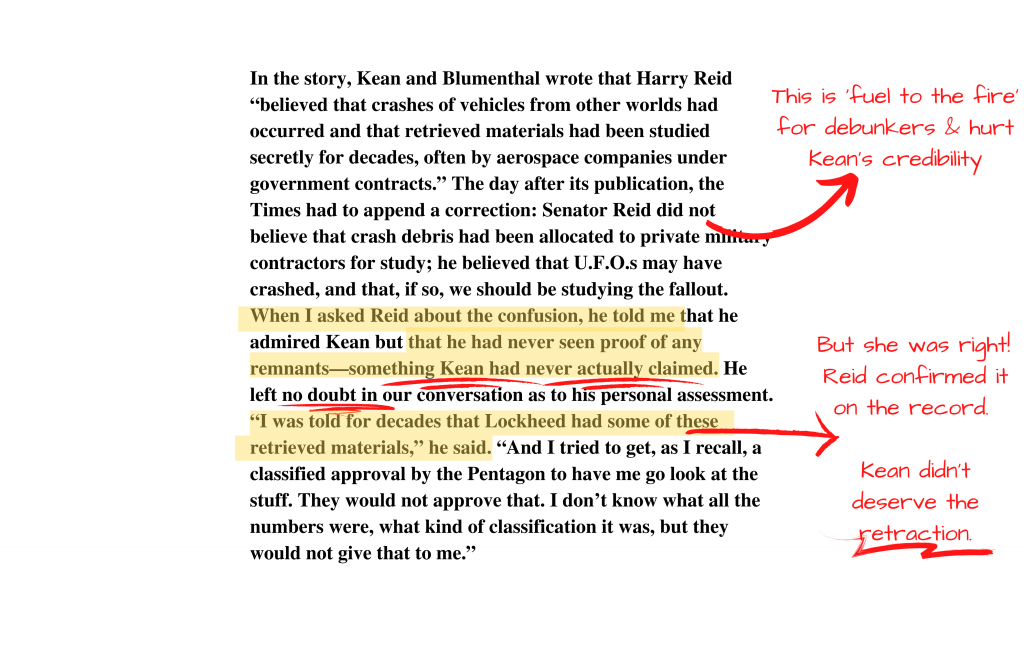

GLK: No,. She had always been very careful to talk about stuff that she had real solid evidence for. And she certainly has what she believes was good evidence for that last story. For me, it crossed some line into something else. Not just people seeing things that they can’t explain, but claiming we might actually have UFO debris. And to me, what was so crucial about that is up until that point, it really is just a story about perception. And what the UFO people are saying, isn’t falsifiable. It’s he said/she said up until the point where we have a crashed spaceship. To me, it was amazing that she got into the New York Times. Now she was heavily criticized after Harry Reid forced them to walk back what he had said. But then when I talked to Harry Reid, I got it. She wasn’t wrong. She didn’t deserve a correction. Harry Reid absolutely does believe that there’s a good chance that there was a crashed spaceship at Lockheed Martin. Even if the slides that she used didn’t pass my personal muster, at that point you have to throw up your hands and recognize that Harry Reid literally believes it. What do you do with that information?

BA: You’ve got documents, videos, TV clips, interviews, Leslie’s book, and more in your reporting. Some of the earliest things you’re referencing are in the 1930s and 40s and you’re also referencing events from the last year. How do you balance everything and how do you steer your focus?

GLK: I’m not sure that every story works quite the same way. What I will say is that you just have to follow the trail of your own curiosity. I read Leslie’s book, and in her book she referred to other books. I went and read those other books. I tried to find all the people who I thought, like her, seemed reputable and just followed those trails out. I think not in every story, but in a lot of stories, you have to fall in love with something. You have to fall in love with the person, you have to fall in love with the subject matter, you have to fall in love with some historical element of something–in order to care enough about the story to write it. I have to write out of affection and warmth. I would say for the first half of my reporting I proceeded as if this was all true. My wife and a good friend of mine at a certain point were asking, “Have you lost your mind? The stuff that you’re saying sounds a little bit crazy. You sound like you really believe this stuff.” I have to at least precede as if I’m convinced to kind of get into the mode of what it feels like to walk around and be convinced. To walk around and think, “How does my barista not know about this famous case?” I think you have to try to try to feel that. And then the second half of the reporting must be, to some extent, not falling out of love, but finding the right distance from that emotion. I didn’t pay any attention to the debunkers or the criticism of this stuff for the first half of my reporting, until I felt like I had a good grasp on like what the believers thought and who seemed more credible. And then for the second half, I focus on what it feels like to believe that this is all bullshit. I read a lot of books by debunkers and the minute that I talked to Mick West, I thought, “Oh, here’s the perfect like foil character.” Just like off to Leslie’s flank there are people who believe we have recovered alien bodies, off to Mick West’s flank, there are equally zealous debunkers. And what I liked about Mick was that he was the mirror image of Leslie. He was reasonable, but he devoted a lot of time and energy to telling people this was bullshit. I started to think about the history of people writing about UFOS. Why is someone inclined to believe what Leslie believes? If we’re going to say this is a metaphor for her Cold War anxiety or whatever–we’ve heard all of that. That’s not that interesting. So, what if we flip that around and what if we take for granted Leslie’s perspective? Let’s take for granted that the universe is bigger and weirder than we think. Then the question is why would you believe what Mick West believes? Why believe the universe isn’t that weird and it’s orderly and normal?

BA: Why believe we’ve figured it all out already?

GLK: What I realized at a certain point was: I wanted a reader to identify with both characters. I wanted a reader to recognize that sometimes they feel like Leslie and wonder why we think we know anything about the world. But sometimes they feel like Mick and feel hardheaded wonder why people believe crazy bullshit. I wanted that to feel like elements that all of us have all the time, or at different times. Then the writing became how do you balance these two feelings? How do you balance the feeling that this might be right and that the world and the universe might be completely different than we imagine with the feeling that this might be insane?

BA: How does falling in love with some part of the story and proceeding as if you believe affect your research process?

GLK: One of the things that I like about this work is that I get to adopt a reportorial persona. I tend to be kind of an annoyingly knowing person in real life. What I like about this is I go into everything as a total idiot that knows nothing. I never lie about anything, but I certainly have ways to suggest I am open to what sources are saying. That’s the main thing, project openness to what both sides are saying. And then it’s a matter of trying to suspend my own judgment as long as I possibly can.

BA: What you see your role on the page in this piece as?

GLK: I felt like my role in this piece was occasionally, when it felt necessary, to reach out to the reader and say, “You might feel a little weird about where we are at right now, but I too felt a little weird about that. So, don’t worry.” I mean, I want the reader to feel safe. That sounds so cheesy, but you want your reader to feel safe in whatever kinds of reactions they’re having. A reader might wonder, “Am I supposed to be thinking that this is a credible thing to say? Am I supposed to be thinking, this is nuts thing to say?” And those are the times where I have to figure out a way to address the reader and say, “I know that sounds crazy, but bear with me.” Or, “I get that you would feel this is crazy, but there’s a reason we’re going here.” The reader has to trust that it is coming to something and not feel completely destabilized. So particularly with this piece, I thought, I had to stop and make sure that we are on the same page.

BA: That’s a great role to have.

GLK: And that’s why for the first like seven or eight drafts of the story, I had a different opening. I had opened with a [UFO] sighting and one thing my editor kept saying was, “I’m somebody who doesn’t know anything about this. And I’m definitely not inclined to believe it. This opening is asking too much of me. I’m not going to stay with you for a sighting because I just don’t care–because I don’t believe it.” So, I thought about the right way to open this to reach where that person is at. People who are interested in UFOs are going to read it anyway. So the question was where to meet someone who thinks it’s all bullshit. You meet them by showing them somebody who’s kind of a lunatic. You imagine that these people are crazy? You’re right. Here’s what crazy looks like. Crazy looks like there are fifty-seven species of humanoid aliens and you can’t tell them for people. But then you have Leslie standing there hearing this, thinking this isn’t the way to go about it. And so, you’re saying to the reader, “I know you think all UFO people are these crazy people, but I’m going to introduce you to a person who’s sensible. Who’s not crazy. And you’re going to be able to identify with that person.” The decision to open it that was to get preconceptions out of the way. We’re going to meet you where the preconceptions are, and then we’re going to set them aside.

BA: Is there anything that you had to cut?

GLK: Oh, there’s tons I decided to cut. I didn’t actually cut the opening scene. I just shrank it way down and told the story later.

BA: Is there a moment or, or a passage or, or some piece of the writing where the research had some impact?

GLK: There was this one source that had been a Pentagon official who had worked on the UFO stuff. I knew who he was, and I also knew he’d never talked to any other journalists. I had sent him a whole series of emails that he had not responded to I had this idea that after January, after he wasn’t in the Pentagon anymore, I felt like he might talk. At the time I had the story written such that I didn’t have to talk to him. In that version, I had to do a much more speculative ending that argued Leslie’s New York Times article didn’t reveal that the government was taking it seriously. It forced the government to take it seriously. I was saying that, but as my own speculation. And it was very well-grounded speculation, but it was still speculation. When I finally got this [Pentagon] guy on the phone. The story he told me was exactly my speculation. Essentially Leslie revealed this program as if it were a formidable one, which it was not. But then because she revealed this clown show of a program, it created the space for a formidable program. It was just an amazing experience to have somebody say exactly what my suspicion had been. And then I could essentially rewrite the entire ending. Instead of having to end in this speculative mode, I could end having finally talked to the Pentagon guy who really knew [the truth]. I was extremely lucky. I only got one interview with that guy. If I had that interview with him toward the beginning of reporting, I would have been at his mercy of what he wanted to tell me. Whereas the fact that I had already written my speculative ending, I could say to him, “What do you think of the idea that [the government] is coming out and relaxing the stigma? Is that right?” And he said, “That’s exactly it.” If you look at the whole thing as a process of hypothesis testing for me, the first two thirds of something are just shutting up letting people talk. And often it’s the last third where you try out an idea. Because at that point you do feel a little bit more comfortable with your conclusions.

BA: And all this crazy stuff that the reader has just read, he confirms.

GLK: My original idea for the ending was asking what it meant that the government came out and said, “These are unidentified.” To me, that was the signal moment. What does it mean that the government says we don’t know what they are? Is this just a smoke screen for other things? Is this an act of epistemological modesty or epistemic uncertainty on the part of the government in a way that was impossible during the Cold War? Because during the Cold War governments had to pretend they knew everything. Or was this weirdly an act of self-interested charity to relax the stigma so that people will report things like foreign drones. And when I finally talked to the Pentagon guy, he said, “We totally did it just to relax the stigma.” So these things that I had planned to do in this speculative mode, I could actually do very concretely. Which of course is way better and way more compelling and persuasive then doing it speculatively. That was a big thing for me.

BA: As you were researching did you find yourself sliding into a genuine believer or a genuine informed skeptic? How did you wade through the murk and remain objective?

GLK: To me the way you wade through that murk is not by trying to float above it, but by getting into it. To me, a lot of it is about spending as long as I possibly can suspending judgment before I have to figure out what being fair to all these people means on the page. And you know, I certainly never came to a definitive conclusion on my own, but I didn’t feel like a reader had to finish the story with a definitive conclusion. When I thought about what feeling I wanted the reader to take away from the end of this story, it was a sense that this mystery is fun to think about. It wasn’t important to cleanly resolve it one way or the other.

GIDEON LEWIS-KRAUS, a staff writer at The New Yorker, grew up in New Jersey and graduated from Stanford. He writes reportage and criticism and is the author of the digressive travel memoir A Sense of Direction as well as the Kindle Single vNo Exit. Previously, he was a writer-at-large at the New York Times Magazine, a contributing editor at Harper’s magazine, and a contributing writer at WIRED magazine. Gideon co-edited, with Arnie Eisen, Philip Rieff’s Sacred Order/Social Order III, and edited Richard Rorty’s Philosophy as Cultural Politics. He teaches a reporting seminar in the Graduate Writing Program at Columbia. He has lived in San Francisco, Berlin (where he was a 2007–8 Fulbright Fellow), and Shanghai, and now lives in Brooklyn with his wife and two small children.

Cover Image Credit: FBI Records: The Vault – UFO