Saumya Roy didn’t want to be part of the story. As a journalist, she was used to third person reporting. But when she began writing about the wastepickers of the Deonar garbage mountains in Mumbai, she was undeniably part of the story. She met the people who would become the characters in her first book when they sought low-interest loans from the Vandana Foundation, a nonprofit founded by Saumya and her father. Castaway Mountain: Love and Loss Among the Wastepickers of Mumbai chronicles the lives and livelihoods of waste pickers with a focus on the story of Farzana Ali, a girl who grows into a woman on the mountains before nearly dying there in an accident, and the attempts to shrink and shut down the trash dump. As an educated, middle-class woman, Saumya knew she led a life very different from her characters, but she’d come “to see the mountains as the pickers did: bringing the city’s used luck, depositing its fading wealth on the township’s tricky passes” (4).

Sometimes, reporters truly are part of the story. Authors like John Carreyrou in Bad Blood or Ronan Farrow in Catch and Kill were harassed and spied on by the subjects of their reporting, while other authors lead their readers through their reporting and the story, like Clint Smith in How the Word is Passed or Kate Brown in Manual for Survival. Other times, authors are just the ones who have taken the time to sit with their characters day after day, like Adrian Nicole LeBlanc did for Random Family, and they don’t have a clear place in the narrative. But what if, as writers, we occupy a liminal space? What if we’re connected to the story enough that we have to acknowledge it, but we’re avoiding inserting ourselves like a cheap trick or just for the sake of being present? When should we be there? Why should we be there?

These are the questions debut author Saumya Roy had to contend with not once, but twice. Her book was first acquired in August 2019 by Profile Books to be published in the UK as Mountain Tales: Love and Loss in the Municipality of Castaway Belongings. Saumya had written her drafts in third person; that was her journalistic training. But her UK editor wanted her to be present throughout the book—something she was reluctant to do at first. In December 2019, Astra Books acquired the US publication rights. In addition to changing the title to Castaway Mountain: Love and Loss Among the Wastepickers of Mumbai, her editor Alessandra Bastagli wanted the book to be in third person. Both were published in 2021.

When Saumya and I met at the Logan Nonfiction Fellowship at the Carey Institute for Global Good in 2019, I too was struggling with and fascinated by the use of I in longform, reported nonfiction. Among our cohort of journalists, we debated whether or not reporters need or should use the first person. When Saumya and I spoke, again, in March 2021, prior to either editions’ publication, I was surprised to hear that her US editor had asked her to move the narrative back to third person.

After the release of both editions, we talked over Zoom—Saumya in Mumbai, me in Baltimore—about what it meant to insert herself into the narrative and then take herself back out again; the rules we create for ourselves throughout our writing process (and, eventually, in publication); and the question at the heart of these two editions: should we, or under what circumstances should we, include ourselves in our writing?

Kristina Gaddy: In your introduction, you write that in 2013 you followed some of the wastepickers from your nonprofit back to the garbage mountains, “to see if their odd businesses would lead to unpaid loans” and because you wanted to “see this strange place.” But, when did you realize that you wanted to write a book about them?

Saumya Roy: In January 2016, there were fires in Deonar, and the newspapers were saying basically there were police cases made out against the wastepickers. [They believed] that they lit the fires. From my having worked there for a few years, I felt that we [Mumbaikars] had made this place, and it was combustible. So, I thought, why not write a magazine piece to show our connection with this place. I also knew what the people living on our waste are really like. So, I thought I’d write a magazine piece, but the research kept growing, and this wasn’t a six month or one year project. If I wanted to do it, I needed to do it properly.

KG: You have this lovely line, “the trash that piled up outside the apartments Mumbaikars spent their lives working to buy, the cavernous offices they spend their working weeks looking out of, and the malls and multiplexes they retreated to on weekends” (83). Had you thought about the trash in Mumbai before the wastepickers came to your nonprofit?

SR: No. You see the city as you want to see it and they want you to see it. I saw waste going into black bags and clean-up trucks whizzing around the city. I actually thought we were doing a great job with it. Slowly it became clear to me that we were piling it up in a place where we couldn’t see it.

KG: In the Castaway Mountain introduction you write, “…I was only passing through, even as a long-term visitor. In these pages, I have stepped away in order to take readers into a world they created but never visited, so they can step into this mirror image of their own lives” (5). Can you talk about that step back for the US edition, while your UK editor wanted to see you on the page?

SR: This is something that I’ve thought about a lot. When I began writing in 2017, my natural instinct was to write it in third person, even though it had been years since I had worked in journalism. In 2019, when Profile bought it, my editor said, “I love it. The only thing I want is for you to be in it.” She said, “You have these very particular insights. You have a deep, long and meaningful relationship with this place and these people.”

I must say that at first, this threw me completely. I had never written in first person. I felt that [by] being there I was almost showing the behind-the-scenes of a movie, which was all about wastepickers and the waste mountains. But I also thought that if I had a lending relationship with these people, I had to be clear about it. I had stopped lending to them when I started writing.

Once I accepted that, OK, I need to be there, then, who was I? What was this first person voice? I am not a wastepicker, and while I am Indian, I am privileged, and I have to acknowledge my privilege. My voice cannot be one of them. By the same token, I also know this place very well. I can’t go to this place as a complete outsider. So, then I had a conversation with Suzannah Lessard and Adrian Nicole LeBlanc, and they said, just admit who you are, and that brings value, from having known them, known their businesses and this place. I realized there is an insight that I bring, and there is a place for that. In Mountain Tales, there’s not a lot of me, but there is a particular insight that I bring.

KG: One example of a shift you’ve made in the text is from the first person “Later, when I asked Hyder Ali what it was like being trapped in the mountains’ deadly aura,” (49) to the invisible narrator’s “When asked what it was like being trapped in the mountains’ deadly aura…” This is such a small change, but it’s also really big at the same time. You are not asking the question anymore. Did you ever think that taking that step back would undermine the authority you have as someone who has been working with the wastepickers?

SR: I was not. I never felt that I had authority. I felt that I had a relationship with them. Does it acquire more meaning because he said it to me? Not necessarily.

My US editor thought the book was reading like a novel, and that I was coming between the reader’s experience of the story. And, by being there in the introduction and the epilogue, the reader understands my relationship and expertise, but I didn’t constantly need to be reminding them.

KG: When you are describing how Mumbai is preparing for the Make in India global investors conference, even when reading Castaway Mountain, I felt so strongly that this is you, Saumya, who is seeing the planters with flowers and spying lions while driving in slow traffic through the city. It comes from your intimate knowledge of the wastepickers, and also with the city, with the region and local politics. Did you ever find it hard then, once you had put those descriptions in Mountain Tales, to take them out?

SR: Yes! This is a good example of a scene [where it] was hard to take myself out. In a way, it’s a comment on what I thought; how we were making ourselves, how we were choosing to present ourselves. But even though I’m not there, I am there.

KG: As a writer, I’m reading your book and thinking, “How did she write that?” For example, in the opening, Farzana finds the babies in a jar. You weren’t there when she found it. You obviously weren’t there when her accident happened. But your reconstruction of those moments is amazing—we feel as if we were there. What was your approach to reconstructing some of the story’s pivotal moments?

SR: Lots and lots of interviews, many people, many times. The opening scene could so easily have gone wrong, could [have] seemed gory. For one, I wanted to make sure it was true. They got frustrated that I was asking the same thing over-and-over again. There were little bits of memory that changed. The other piece was that I walked the mountains endlessly. How does the sea look? How do their homes look? I recreated it from my own experiences of being there, too. And I used all the documents or reports I could get, even for detail on place, incidents, history and policy.

KG: Obviously, when you reconstruct, you’re not present. Should there be any prescriptive rules for when and where we include ourselves?

SR: This is something that I’ve struggled with. I wouldn’t give any prescriptive rules. When we were talking with Suzannah [Lessard during our Logan Fellowships], she said, “You can’t just pretend you weren’t there.” We are not invisible. I felt that by being there, we were altering family dynamics. Just by writing notes–yes, they got used to it–but they don’t forget it.

Suzannah helped me realize that by being there, in a very slight way, you are altering what’s happening, and you’ve got to be aware of that. And, you need to just flag it [for] the reader.

KG: In a way, I understand your US editor. If you introduce yourself in the beginning, the reader is carrying that the whole time. But in a way, when you insert yourself more often, we see that you are there all the time.

SR: I do think that writers need to be aware. Be questioning yourself. Even if you are not there as I, you are there. You still have to ask the same questions.

We are also having real relationships with the characters, and those have informed the book. Be aware of those relationships, when people are telling you certain things, [or] not telling you certain things. When you are aware of yourself, you try to come at the reporting in different ways. You may want to ask other people. Ask three or four different people, get different perspectives and try to triangulate what happened or form your own opinion.

KG: I might argue that there’s not enough of that questioning in nonfiction books. I once asked writers if they could give me a good example of a nonfiction book where a writer was questioning on the page, “Am I the person who should be writing this book?” And I didn’t really get any good answers.

SR: The exploration of that is a worthwhile question. As a writer, you have to question yourself. So, it’s a painful process, but you have to go through it.

This was something that haunted me a lot. Today, there are a lot of ways to document our lives—YouTube, social media, etc. So, if someone were to give the wastepickers a smartphone, they could videotape their own lives. And, maybe not have a book written in English, but it could be a documentary, where they have spoken about themselves. So, is it that I am writing this book because I can speak English? I questioned myself.

But this is the heart of writing–understanding another person. Even the lack of authority is a voice, the questioning, the probing. Do not write from a position of authority, always, but write as a seeker, a searcher. Someone who is searching for the answers to this place, what it means to our society.

The most important position that a writer holds is that of a seeker. You are seeking for the reader. Not an authority speaking down to them, but seeking on their behalf.

KG: I see a lot of discussion of “What’s true?” or “What is creative nonfiction?” But I’m a little bored by that because we must always begin with the fact that we, as writers, are seeing the world in our own way. It’s true that you were present throughout the reporting, but is it no longer true if you’re not present on the page in those moments? We get to shape the narrative—something might have happened to Farzana, but it doesn’t fit into the arc.

SR: And we’re the ones deciding what the arc is!

KG: Exactly! We are deciding what stays and what goes. And even if we were to give Farzana a camera and make a documentary, unless you just ran all the raw footage, there would still be someone cutting the footage together, determining what is an exciting scene or part of the story.

SR: One of the things that is there in my book is the top-down and bottom-up. On the one side are the court and municipal officials, and you could say that is the “authority,” the unalienable truth that came from documents. Then there is, how do these people experience the policy, and the failing in policy? I have not given one narrative more authority over the other.

There are multiple truths. The truth is what you see in court and read in policy documents, but the truth is also the emotional truth of what the wastepickers experience. And neither is less or more than the other. As a writer, you have to be open to those multiple truths and multiple realities. That was a challenge, but it had to be there.

KG: The balance of that technical–what’s going on at the municipal level–and the action happening down on the mountains, that was so well done. I think that’s hard a lot of times for nonfiction writers because we need the action and characters, but at the same time, you have to include the background or the official version.

SR: At first my intention was to only show the story through the wastepickers lens. But there are a lot of stereotypes about the poor. I thought it was important for me to show the big forces pressing down on them. They were not lazy. They were working very hard. If you’re not showing those forces, then you are feeding into the stereotypes about the poor. It was important for me to show those policy delays and their impact on these people. The mountains are also made by us, by policy delays, by court delays.

We learn in journalism school that people like people. Now, if I say I want to show legal delays, people might think, “What?” But it was very important for me to make that interesting.

It’s in that tension between people and policy that the story lies.

KG: I’m glad we got around to this. I wasn’t sure how this balance was related to you writing in first or third person, but acknowledging who you are, and that you understand policy and the people is part of your positioning and ability to tell the story well.

SR: As journalists and writers, when we focus a lot on failed policy, on the corruption, or technocratic solutions, we can also forget the impact it has on people. It’s not a victimless crime.

SAUMYA ROY is a social entrepreneur, journalist, and activist based in Mumbai. She co-founded Vandana Foundation in 2016, a non-profit that provides microloans to entrepreneurs in Mumbai and rural Maharashtra. She has written for Forbes India, Mint newspaper, Outlook magazine, wsj.com, The Wire (India), The Wire (China) and Bloomberg News, among others. While working on Castaway Mountain, Saumya received fellowships from the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Center, Blue Mountain Center, Carey Institute for Global Good, Sangam House, and Dora Maar House. In 2019, she appeared on the Solvable podcast series, featuring those working to solve the world’s most intractable problems.

KRISTINA GADDY is the author of Flowers in the Gutter: The True Story of the Edelweiss Pirates, Teenagers Who Resisted the Nazis and the forthcoming Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History. Her writing explores and highlights forgotten and marginalized histories, and has appeared in The Washington Post, Baltimore magazine, Washington City Paper, Baltimore Sun, Bitch Magazine, Narratively, Proximity, Atlas Obscura, OZY, Shore Monthly, among other history and music publications.

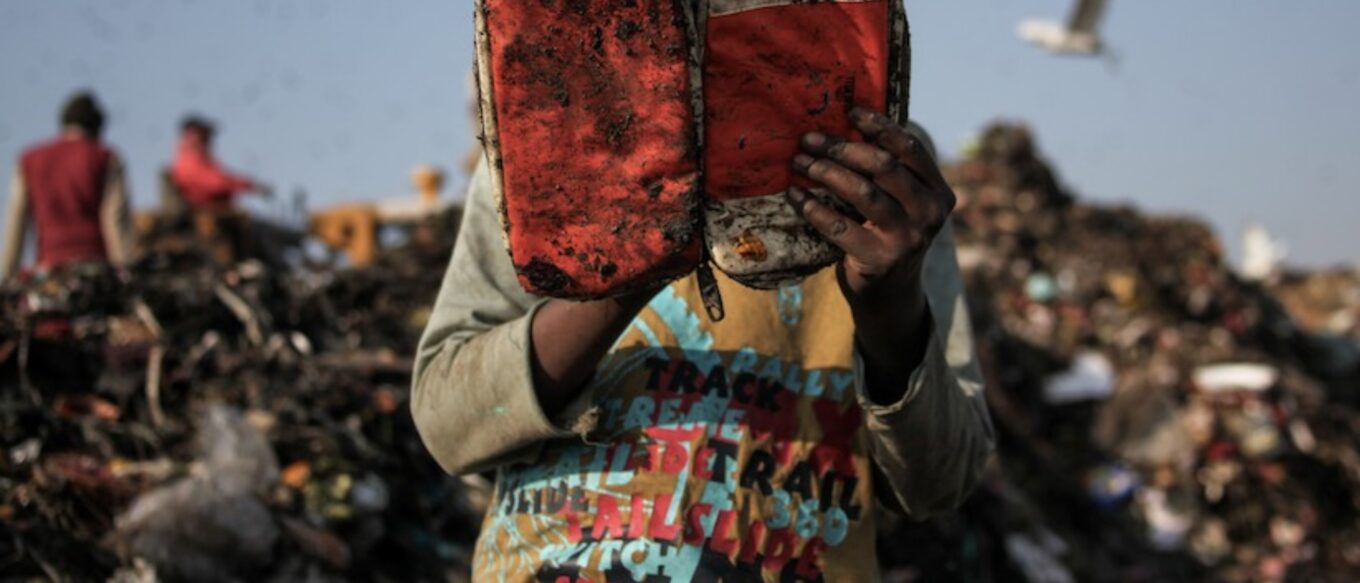

Cover image from The Global Alliance of Wastepickers.