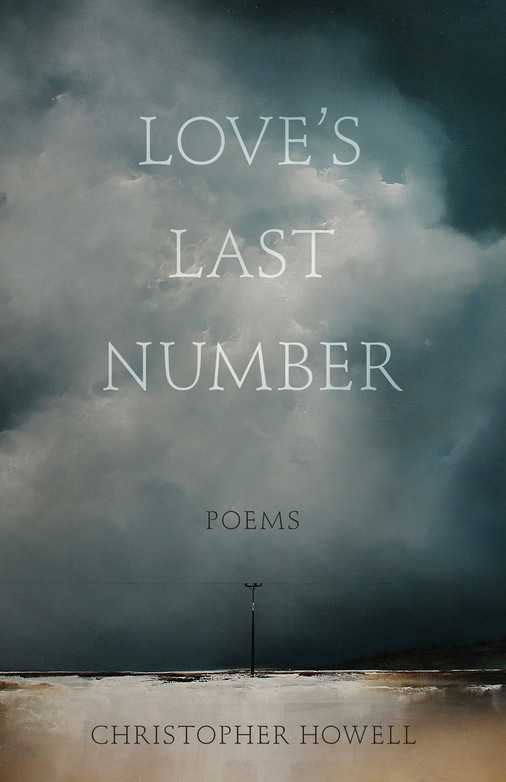

Christopher Howell, a professor of poetry at Eastern Washington University, has written extensively about loss. His most recent book, Love’s Last Number, was published by Milkweed Editions in 2017. “Homecoming,” included below, is from his forthcoming collection, The Grief of a Happy Life. It originally appeared in Poetry International.

Christopher Howell, a professor of poetry at Eastern Washington University, has written extensively about loss. His most recent book, Love’s Last Number, was published by Milkweed Editions in 2017. “Homecoming,” included below, is from his forthcoming collection, The Grief of a Happy Life. It originally appeared in Poetry International.

I met Chris when I took his poetry workshop as a student in the MFA program at Eastern Washington University. Shortly after meeting, I learned that his daughter Emma had died some years before. A decade later, grief entered my life after my husband Jaylan died of brain cancer. Recently, I had the opportunity to talk with Chris about how grief operates in our lives, and what it means to write about it. Our conversation took place on San Juan Island, where he was writing in residence at the Helen Riaboff Whiteley Center.

NICOLE HARDINA: You’ve said, “Poetry, for me, is the only means of reconciling the objective, everyday world with the inner life, the ego with the self. In that reconciliation, that enactment, it seems to me very like worship: a humane and primary response.” It sounds like you’re describing the emotional work of living.

CHRISTOPHER HOWELL: Yes, but I don’t mean to imply that people who don’t write poetry are not emotionally alive. That reconciliation has to occur somehow, or most of one’s experience simply becomes old news rather than an aspect of one’s self. It’s often said that everyone writes poems, it’s just that most people don’t write them literally. I’m not so sure about that, but I’m willing to hope for it.

NH: That suggests that everyone makes meaning.

CH: I think that whatever meaning there is is made meaning. I also think that haphazard encounters with the need for meaning sometimes dissolve that need for people. It doesn’t affect their conduct or their thinking or their feeling. It’s momentary. And I guess one thing that writing does is keep things from being momentary. It creates this text with which then you have an ongoing relationship, and other people may encounter in a profound way, conceivably, also.

NH: Does poetry enable us to hold space for the existence of opposing truths?

CH: Oh, I believe so. That’s negative capability right there, on the hoof. Contemporary life offers many opportunities to put negative capability into play. There is so much contradiction, and I think we internalize a certain amount of that, inevitably. Any discipline that you might be drawn to is a sort of defense against the internalizing of contradiction; or perhaps it offers a means of expelling contradiction from your inner life. And this agent could be any of a number of things. Writing certainly fills the bill. But it might be yoga or meditation, or Tai chi. Swimming. There are a lot of meditative states that may bring a person into connection with the sources of meaning, which are intuitive.

NH: Does it have to be intentional?

CH: My experience, which is most of what I have to go on, tells me that writing is a way of contacting intuitive knowledge, and you do that kind of intentionally, but I also think that some of that intention itself is unconscious. I don’t know how else to put it. For instance, I’ve been here a week, and I’ve been writing every day for several hours, but I can tell when I’m sitting down to do it and consciously pushing myself to do that, and when I’m sitting down to do it because I’m being brought to it in some kind of tidal way. The result may be the same, but the role of intention can be different.

NH: In “The Principal Uncertainty,” from your most recent book, Love’s Last Number, you write:

Is there elegy enough for this: women

and beauty and men and death

and the moon?

god’s loneliness enters it

all, like the night air after a storm

when there is nothing to do but breathe

and listen

for the voices of those who survived.

Why should we listen to the voices of survivors? What do they have to tell us?

CH: Well, the first thing they have to tell us is they survived, and that life and consciousness are ongoing, that all manner of disruption and distress, short of death, are survivable. It’s quite possible that even death is survivable. But also, “those who survived” are like travelers who have returned and they have things to tell us.

NH: The title is a play on Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle.

CH: The basic idea, mathematically, is that it is not possible to chart both the speed of an object and its location.

NH: There’s a limit to what we can know. Your question, “is there elegy enough for this?” seems to get at that.

CH: The lynchpin of that phrase, “there’s a limit to what we can know,” really is “know.” The nomenclature deserts us here. What is knowledge? How do we know we know? What other word might we use for the knowledge which is not frontal, but which is almost graduated or continuous? Do we know what we are starting to know?

NH: In a previous interview, you said that you want your poems to start from a point of knowing, go toward the unknown, and then come back to the known. Why is it important that a poem take that journey?

CH: That’s bringing the inner life to active life and active consciousness or response. It’s always there, the inner life, but if you don’t visit, you are a captive of the ego rather than, say, a “survivor” with something to tell. And if you visit but bring nothing back, all of that understanding you might have found remains hidden from you, like a dream that fades upon waking.

NH: That sounds like the writer’s experience. Is it the same for the reader?

CH: It should be. That’s the ideal result, that the reader of a poem feels as though he or she is writing it. That’s when you know it’s really working, that that transference is occurring. What I have been saying is, I suppose, redolent of Joseph Campbell and his notion of the hero’s journey. It’s the same thing.

I don’t feel all that heroic, but there’s a lot more in the unconscious than ecstasy. There are a lot of creatures and rooms, and a lot of them are dark, so it’s not a foolish or pastel experience to enter there. I think that our pragmatic society staunchly maintains the assumption about poetry and poets that we’re sort of flimsy and sentimental and irrelevant. But, I think it’s important work.

I’ve been reading all this Scandinavian stuff and have been reminded again of the poet as a kind of official guide to the communal unconscious, the collective unconscious of the group, of the tribe. It’s an incredibly important function to bring the group to an actualization of meaning, of significance. It’s a priestly function, I suppose. We’re way past that in our atomizing society, but the need for it persists. Were that not so, we would not be inhabiting our current political moment full of contempt, bullying, incivility, and lies.

NH: Even people who would argue that poetry is irrelevant might turn to it in times of import.

CH: Yes, they do, and I always hope they will remember doing so, and think about it.

NH: I’ve been thinking about the way poetry pushes back against cultural norms surrounding grief. There’s social pressure to transcend grief, which I think is shorthand for “look away.”

CH: Elisabeth Kübler-Ross has given us her notion of the “stages” of grief. I think that’s bogus. What is a stage, anyway?

NH: Subsequent research has debunked the stages, but people still believe in them.

CH: I think the so-called stages pretty much occur all at once, and that the real goal is not acceptance—it’s integration. You live with the loss, and the loss lives with you. The only way to hang on to your affection is to hang on to the loss. You have to make peace with it. It’s not an acceptance thing. It has to become part of your life, I think, and I do think that writing provides a pathway to that kind of acknowledgement, that yes, this is part of my life. Part of me. We live together, and it is together we will go forward, informed by each other.

NH: In a poem called “An As Though Prayer,” you write:

I pray for the ache

that keeps me and the staircase

of that keeping. I pray for the soft

recumbence of moss, that memory

not desert this.

That’s been an impactful image for me, the image of the endless staircase of the keeping and the simultaneous feeling of burden and blessing of it—of wanting to keep the only thing that you can keep.

CH: People sometimes feel they’re betraying the person they have lost by continuing, themselves, to live. I think the view of loss and grieving I’m suggesting—that it must be integrated—is a hedge against that kind of thinking.

NH: Can we acknowledge our shared experience of loss? I lost my husband to cancer recently. Early on in our relationship, I learned that you’d lost your daughter, Emma, who died in an accident. In my grieving experience, I’ve found mentorship in your writing for how to be, how to grieve—just, how to live with it as a person and as a writer. Thank you for that.

CH: I feel honored by that, and happy for both of us. What better result could there be? Still, you’ve been through a terrible thing and seem to me to be working with it in exactly the most generative way.

NH: Did you have mentorship in grief from writers or from others?

CH: I had a friend who lost his son. I think about his response to that loss, and his kindness to me and my family. There was certainly some mentoring there, and it was done out of his goodness, but I’ve also always felt that there was some instructional impulse, that he wanted to give me a menu of ways of relating to what had happened.

In terms of poets, the poets that I’ve admired most have all had a kind of elegiac posture because that’s part of what the world requires, of what life requires, that we not let it pass without noticing it.

James Wright and the way that he approached this temporary condition, or the temporariness of our condition, certainly has meant a lot to me and taught me not to throw away my experience, regardless of its quality or nature.

NH: Do you think that you have an instructive impulse, as a writer?

CH: In the writing itself, you mean? It is not conscious as instruction. I’m aware when it feels to me as though transference can happen. For me, part of the project of becoming a poet, of learning and becoming better, has been to refine my receptors so that I have some sense of when the transference is possible—when the poem for the reader will be not a proposition, but an experience. You could say that it’s teaching or mentoring, but it’s more like communion.

NH: Reading your poetry before grief came into my life and after, there are big differences. Now I can read it with the purpose of checking my experience against yours. I realize that your poems are not just direct reflections of your experience, but that’s one effect that I appreciate. They demonstrate commonality.

CH: That’s a great compliment. As I said, “communion,” I hope the poems enact it in the way the poems I love, by others, enact it for or in myself.

NH: One of the things that I’m interested in, going back to the poem, “An As Though Prayer,” is the idea that the pain of being on that staircase and the solace of being on that staircase are so very close together.

CH: Yes, they are. Exactly.

NH: Suddenly, in grief, everyday life is a constant facing of dichotomies: the joy of love, the sadness of loss, and both at the same time. You’ve said that the two states are “a micron apart.” In The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Kundera writes something similar. Writing about the death of Stalin’s son, he writes, “Rejection and privilege, happiness and woe – no one felt more concretely than Yakov how interchangeable opposites are, how short the step from one pole of human existence to the other.” I feel like the fact that there’s not much distance is self-evident, but I wonder how much the work of writing about it is about measuring the distance.

CH: Of the poems that directly address that for me, one of their outcomes is measurement, but it’s not a conscious intention. In the same way that history has to be continuously rewritten, that measurement, that distance is recalibrated, but it’s so organic that calibration almost doesn’t quite fit as a descriptor.

NH: Maybe as soon as you’ve measured it, it moves.

CH: Well, again, the measurement is not a separate abstraction. The measurement is in the act of measuring, so again, the result is an intuitive result. It is the sort of result out of which we get the music of Eric Dolphy and poems of James Wright and W.S. Merwin and Laura Kasischke.

NH: I think there’s satisfaction in acknowledging the proximity of the joy of love and the sadness of loss. For me, the experience of grief is one in which there’s only so far that I can go toward answering a question. Maybe I don’t even know what the question is, but there’s only so far I can go in thinking about it before I’m doubling back on myself, and in the end, I come to this place of just thinking, “What a mystery.” But there’s satisfaction in contending with it, in looking at it.

CH: Yes. Also, I don’t really think you have a choice. You have to do that. I’ve been emailing back and forth with a friend who lost her husband in 2011, and she just kind of went into a cocoon. And I don’t think she was at all bothered by that. It was simply the place to which she had to go in order to “look at it,” the means by which she sought to integrate the situation.

Speaking of what’s necessary, we were going back and forth a little bit ago about the afterlife. I had another friend who was a death and dying nurse on the children’s ward at the Group Health hospital in Seattle. She said she always told the parents that they should expect to hear from their child. And she said it always happened. (It did happen to me.) My friend said it had happened to her as well. It’s interesting. I suppose psychologists would say it’s a protective psychological mechanism that gets tripped by loss, but I don’t care. I mean, why would you care if it’s a psychological mechanism or not? The experience itself is a real experience.

NH: I’ve had that experience, in dreams. I remember being grateful for having what felt like a new experience with Jaylan because my default assumption had been that no new experiences were possible.

CH: I think our relationships with the dead continue to grow. I feel differently about my parents than I did before, and I can recognize that that’s been an ongoing thing. That’s the way of it, if you let it happen, and it is in your interest to do so, not to cut yourself off.

NH: As a writer, you’re documenting that process. You’ve said that your process is not intentionally to document anything, but to listen for what comes and follow that. But what comes is also what comes into your life. What do you think the value is, culturally, in documenting grief?

CH: It offers news from the other world. And, hopefully, it says grief is not a hammer. It’s more like a blanket. It’s not to torment you. It’s the underside of your affection. I think if people get that out of the poems, then that’s a good result. The documenting though, is the formal part. It has an important link to the living, but they aren’t the same thing in the aftermath, and some poems are spoken out loud, spontaneously, and that becomes the sole substance of their documentation.

NH: You have a book coming out called The Grief of a Happy Life. Can you talk about the title?

CH: It’s the last line in the book, and it goes back to what I was saying about grief and affection being a nexus of value in one’s emotional life. You can’t quite separate the two. There’s no life into which grief does not enter. There are, unfortunately, lives that have very little happiness in them, which seems to me the real tragedy of our human situation. You should have both of those things. If you’re going to have grief, you have to have some happiness. And in a way, grief helps you understand happiness.

Do you want to see the title poem of that book? Would you like me to read it aloud?

NH: I would love it.

CH:

“Homecoming”

I put on my good black shoes, my shirt

of grey softness that reminds me of luck,

and the blue hat given me

by a child who left

this earth that even her shadow

made so beautiful.

And then, well, I set out

down the clamor of roads

and, almost by accident, onto paths

through dense apothecaries of evergreen and fern

and finally to meadow and orchard

risen from the dead into a contentment

that did not know me

and wouldn’t take my money or my name.

Did I not see I was the same no one

who had lived there always

and could never return?

Did I not perceive the multitudes

waving their arms like wind to be known again

and gathered like pieces of a god?

How many many years, how much spent blood,

to unpilgrim ourselves, to stand before an empty house

glistening with the grief of a happy life.

NHA: It’s beautiful. Thank you. In “Homecoming, you’re coming home to the empty house. You have a line in another poem, “Does everyone come home at last to ruin?” And here, the ruin is also the starting point.

CH: Well there’s that seeming contradiction between leaving and arriving. But when you’re speaking about the self, you’re speaking about both things continually happening at once, the energy and darkness spinning off of that. The Buddhists would say they are the same thing, though I think they are distinct, that they illuminate each other, and the illumination itself is greater, more significant, than the answer to the question, “Who am I?” or “Where am I going?” Still, those questions are enduring aspects of our mortal being.

NH: When Jaylan was sick, we started going to these meditation retreats at the Buddhist temple in Ballard. The focus of one was about grasping and wanting. Afterward, I spoke to the nun and told her I was struggling with wanting. My basic problem was unsolvable because I didn’t want Jaylan to be sick, and he was. She said, “We have very little control over what we want.” I really appreciated that. It’s helpful to be able to identify these concrete moments of leaving and arrival.

CH: That’s right.

NH: Because it tells you something about what you don’t know, or maybe what you’re beginning to know.

CH: Or what you’re knowing all over again.

NH: Or what you have to continuously relearn. The opportunity to make grief visible is important to me, and I wonder if that’s something that you share.

CH: I would say tangible, rather than visible. We were talking about the writing and how it continues on, that it has this objective being, and that you re-relate with the text as something that’s been written, and so you make it tangible. You’re making an aspect of the inner life tangible, and that seems important, seems part of the job. Writing about grief reinforces this notion of it as something you possess. It’s not something that afflicts you although I can certainly imagine situations that are so extreme that there’s practically no way to avoid the notion of affliction.

NH: I think time must be required in order not to feel afflicted. For me, for at least six months after Jaylan died, it was just affliction in the sense that it edged out everything else.

CH: I’ve got to agree with that. After Emma died, I wept so much that my vision improved. I didn’t realize that that could happen. All kinds of things would set me off, for a while.

NH: I’m thinking about grief being visible. One of the poems from your collection, Dreamless and Possible, is titled “Mercy.”

The last stanzas read:

When mercy finally woke, it must have been a little dazed and wondering

to find such dark

crowding its shoulders and me like a nickel’s worth of glass

asking, wrongly, for death

to be undone. I didn’t care. I said these are my bones, all I have for an offering. Just

give back her life. Take mine.

And mercy took hold my hand, so I could turn and face the world and say this,

but that was all.

To me, part of what’s merciful is the way the poem has made the initial actions of grief visible or tangible. There seems great importance in having the opportunity and the ability to face the world and express the depth of grief, which you’ve been doing for a long time.

CH: It’s true. It’s been quite a while now. It was seventeen years ago. I’ve written several elegies for Emma while I’ve been here and in the last year. I keep thinking that I’m through writing those, but again, it’s a process, it’s not an event. You write what comes, in the same way that the body takes what it needs during meditation—if you go to sleep, that’s what you needed. If I find myself writing about Emma, or about the Vietnam War, or about the farm on which I grew up. I don’t kick myself for being unimaginative; I accept the gift of it.

NH: In the foreword to Slim Night of Recognition, the collection of Emma’s poetry that you published after her death, you wrote, “Nothing about our relationship can be replaced, and every day I wonder how I can possibly live without it. And every day, of course, I simply go on, for lack of a more viable option.” You wrote that Emma would tell you that “this nexus of longing and the actual is important, to write toward it and fully experience its value.” That was in 2006. What seemed to be the value of that nexus at the time, and how has it changed?

CH: At the time, I had just finished going through her manuscripts, and it had made her much more present and made the loss much more present, correspondingly. I would say now it’s kind of like revisiting her, almost, to touch that spot again, and it’s reassuring.

NH: That it’s still there?

CH: Yes, and that the best part of myself is still here.

CHRISTOPHER HOWELL’s eleventh collection of poems, Love’s Last Number, was published in 2017 by Milkweed Editions. His poems, essays, and translations have also appeared in a number of anthologies and journals, including Antioch Review, Colorado Review, Crazy Horse, Denver Quarterly, Field, Gettysburg Review, Harper’s, Hudson Review, Iowa Review, Northwest Review, Poetry Northwest, Southern Review, and Volt. He has been the recipient of three Pushcart Prizes, two National Endowment Fellowships, two fellowships from the Artist Trust, and the Stanley W. Lindberg Award for Editorial Excellence.

CHRISTOPHER HOWELL’s eleventh collection of poems, Love’s Last Number, was published in 2017 by Milkweed Editions. His poems, essays, and translations have also appeared in a number of anthologies and journals, including Antioch Review, Colorado Review, Crazy Horse, Denver Quarterly, Field, Gettysburg Review, Harper’s, Hudson Review, Iowa Review, Northwest Review, Poetry Northwest, Southern Review, and Volt. He has been the recipient of three Pushcart Prizes, two National Endowment Fellowships, two fellowships from the Artist Trust, and the Stanley W. Lindberg Award for Editorial Excellence.

NICOLE HARDINA’s work has appeared in the Bellingham Review, the Truth about the Fact, the Seattle Poetic Grid, and elsewhere. Her book, Little Washington, an exploration of the smallest incorporated towns in Washington State, is forthcoming from Keen Adventure Publishing. She received a grant from Artist Trust for her memoir in development, When I Spin Away.

NICOLE HARDINA’s work has appeared in the Bellingham Review, the Truth about the Fact, the Seattle Poetic Grid, and elsewhere. Her book, Little Washington, an exploration of the smallest incorporated towns in Washington State, is forthcoming from Keen Adventure Publishing. She received a grant from Artist Trust for her memoir in development, When I Spin Away.