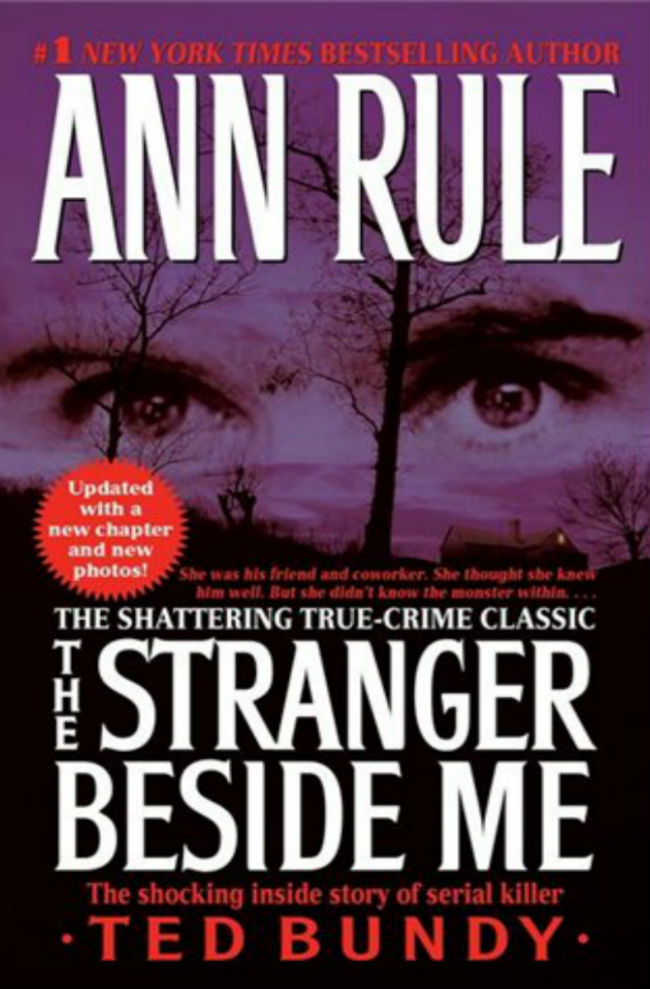

There is only one copy of The Stranger Beside Me in the bookstore where I work. It is small and fat, a mass market paperback, and probably the copy you’ve seen a thousand times. The cover features a large set of eyes looming behind a vista of barren trees and a house in the foreground. In a garish purple and red color scheme, the book proclaims: “She was his friend and coworker. She thought she knew him well. But she didn’t know the monster within…” This book looks pulpy, like it could be a cheesy romance novel (which would be fine, if that’s what it was), like you should be able to find it at the grocery store. Unlike many of the books we keep on our shelves, which come multiple editions: in trade paperback (the “normal” paperback edition) or hardcover, large print or audiobook even, and which we can gladly order for our customers, this is the only format it comes in, aside from a pricy hardcover anniversary edition. If you want to read Ann Rule, you’re reading her from a 9.99 mass market paperback.

As much as the adage “don’t judge a book by its cover” might be true for assessing grade school classmates, it’s decidedly not useful in a bookstore. There is, of course, no one-to-one relationship between the extra-textual aspects of a book and its content. But the cover, size, shape, and design of a book do represent a level of care (or is it expectation) from publishers, publicists, and writers—and those are the people who shape the world of books, in some very real ways. As a bookseller, when a new book comes across the receiving desk, the way that it looks is the first information I have about it, and I can usually determine—though not always—where a book belongs on the floor by looking at its cover. Children’s books are the most obvious, of course, but a YA title or two has found its way onto the adult floor before an enterprising coworker noted its misplacement. Most adult books are similar in size and shape, with newer fiction covers adorned with trees or flowers, a white paint-looking font looming in front of or behind the flora, while new nonfiction books feature a stark one- or two-word title, all in capital letters. Poetry and drama are slim, and the few fat mass market editions we carry belong in Sci-Fi, Mystery, or True Crime. These editions are fatter and shorter than their svelte alternatives and they are cheaper—for the publisher as well as the consumer. Their titles tend to be genre specific, dependable backlist—books that will sell, but perhaps which are not so impressive nor culturally elevated to be given a more standard package. The Stranger Beside Me has fit comfortably in this category for years.

As much as the adage “don’t judge a book by its cover” might be true for assessing grade school classmates, it’s decidedly not useful in a bookstore. There is, of course, no one-to-one relationship between the extra-textual aspects of a book and its content. But the cover, size, shape, and design of a book do represent a level of care (or is it expectation) from publishers, publicists, and writers—and those are the people who shape the world of books, in some very real ways. As a bookseller, when a new book comes across the receiving desk, the way that it looks is the first information I have about it, and I can usually determine—though not always—where a book belongs on the floor by looking at its cover. Children’s books are the most obvious, of course, but a YA title or two has found its way onto the adult floor before an enterprising coworker noted its misplacement. Most adult books are similar in size and shape, with newer fiction covers adorned with trees or flowers, a white paint-looking font looming in front of or behind the flora, while new nonfiction books feature a stark one- or two-word title, all in capital letters. Poetry and drama are slim, and the few fat mass market editions we carry belong in Sci-Fi, Mystery, or True Crime. These editions are fatter and shorter than their svelte alternatives and they are cheaper—for the publisher as well as the consumer. Their titles tend to be genre specific, dependable backlist—books that will sell, but perhaps which are not so impressive nor culturally elevated to be given a more standard package. The Stranger Beside Me has fit comfortably in this category for years.

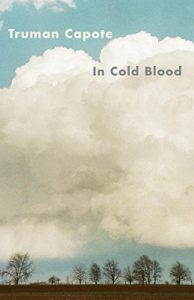

This is not true of all true crime—Truman Capote’s true crime classic (though whether we would classify his work as “true” today is contentious) exists in a fancy trade paperback from a reputable imprint. It suggests only the utmost seriousness might lay within its pages—real literature. Capote and Rule are different writers who told different stories, but they are united by their fascination with crime and their genre—yet the extra-textual aspects of their works are polar-opposite. And maybe that is fair—maybe Capote’s writing was more writerly, I thought before reading the book itself, and Rule’s prose warrants the packaging she has been given.

This is not true of all true crime—Truman Capote’s true crime classic (though whether we would classify his work as “true” today is contentious) exists in a fancy trade paperback from a reputable imprint. It suggests only the utmost seriousness might lay within its pages—real literature. Capote and Rule are different writers who told different stories, but they are united by their fascination with crime and their genre—yet the extra-textual aspects of their works are polar-opposite. And maybe that is fair—maybe Capote’s writing was more writerly, I thought before reading the book itself, and Rule’s prose warrants the packaging she has been given.

The Stranger Beside Me was written in 1980 and is a now-typical blend of genres—memoir and reporting. In it, she recounts her experience working side by side with Ted Bundy at a crisis hotline, as she realizes her kind former coworker is actually a prolific and terrifying serial killer. When I began reading the book, I was wary of it, frankly concerned I might find a salacious and old-fashioned hagiography of Bundy. Instead, I found a thoughtful victim-and-author-focused narrative that actively dispelled any notions of Bundy as a misunderstood hero, belaboring the fact that there was no true kindness beneath his handsome face. The book is not without its flaws, and remains of its time, but it is good: thoughtful, well-paced, and contains the right balance of her personal story as it related to his. I now realize I had been tricked by the cover of the book, convinced by the packaging that Rule’s writing would not be thoughtful, not wise, not “real art.” I’d been setup—by printing format and cover design, alone—to see her book as a tawdry mass market paperback.

Soon, though, scores of potential readers might be saved from such a misconception. After nearly three decades, The Stranger Beside Me will be reissued this fall in an elegant trade paperback version. In part this reissue is probably attempting to capitalize on the upcoming biopic about Bundy, “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile,” but the story within it will remain, I assume, the same. Rule died in 2015, so I am not anticipating any new material or framing device (the book was updated and amended many times since over the years, last updated in 2008). The imprint’s publicity team did not respond to my request for more information about this new edition, but I think the reissue is more than merely a movie tie-in (which it is not). In fact, I think that the reissue suggests a new and well-deserved direction in true crime—not necessarily in its writing or craft, but in the way it is viewed to the outside world.

As Vulture, Bloomberg, The New York Times, and others have pointed out, true crime is having a moment. There is a definite uptick in the production value of true crime stories, as well as new media claiming spaces for them. Making a Murderer, The Jinx, and other documentary works seem packaged for a new generation of true crime lovers. And podcasts poring over every minute detail of a single crime abound. Serial kicked off this trend, followed almost immediately by well-produced investigative works that explore old cases like Someone Knows Something (which proved ultimately incorrect in its titular assertion), In the Dark, Stranglers, and West Cork. Others focus on a crime or two each episode—the soothing voice of Criminal’s Phoebe Judge delves deep into little known aspects of little-, or well-, known cases—while Sword and Scale plays on visceral shock value, using primary documents—including 911 calls—to tell a full story. Last Podcast on the Left and True Crime Garage each feature two male hosts rehashing true crime stories while engaging in good old-fashioned radio camaraderie.

As Vulture, Bloomberg, The New York Times, and others have pointed out, true crime is having a moment. There is a definite uptick in the production value of true crime stories, as well as new media claiming spaces for them. Making a Murderer, The Jinx, and other documentary works seem packaged for a new generation of true crime lovers. And podcasts poring over every minute detail of a single crime abound. Serial kicked off this trend, followed almost immediately by well-produced investigative works that explore old cases like Someone Knows Something (which proved ultimately incorrect in its titular assertion), In the Dark, Stranglers, and West Cork. Others focus on a crime or two each episode—the soothing voice of Criminal’s Phoebe Judge delves deep into little known aspects of little-, or well-, known cases—while Sword and Scale plays on visceral shock value, using primary documents—including 911 calls—to tell a full story. Last Podcast on the Left and True Crime Garage each feature two male hosts rehashing true crime stories while engaging in good old-fashioned radio camaraderie.

But no podcast has done more to invigorate the public perception of the genre than the hit show My Favorite Murder (MFM), hosted by two women who discuss, among grisly murders and horrifying mysteries, their pets, mental health, their former drug abuse, and vintage dresses. Currently number 11 on iTunes’ overall podcast charts, and number 3 in comedy, MFM listeners, largely young women, are so-termed “murderinos.” They routinely sell out huge venues, spend money on merch, and craft intricate gifts and wares based on the show. Hosts Karen and Georgia, as fans consistently and casually refer to them, have become internet and even real-life celebrities, garnering attention from such outlets as The Atlantic and The New York Times. Along with their smash hit podcast came questions and concerns about ethics in true crime and how a program could be somehow both true crime and comedy, and of course, the inevitably questions about why and how anyone could be interested in these horrendous stories.

Karen and Georgia are the first to admit that they didn’t invent being obsessed with true crime and maintain that they are merely tapping into the wide base of people latently obsessed with the genre, for whatever reason that may be (and those reasons, though fascinating, are largely beside the point). In addition to their true crime discussion in each episode, Karen and Georgia almost always mention some their recent media obsessions—from television dramas (Mindhunter and The Sinner were both mentioned) to new novels (Georgia recommended Noah Hawley’s Before the Fall) and recent nonfiction (Karen was recently engrossed with John Carreyrou’s Bad Blood), and sometimes classic true crime: Helter Skelter, Zodiac, and, yes, The Stranger Beside Me. In some ways, MFM may be functioning as the socially acceptable reason gateway to media we may have been too squeamish to pick up before now.

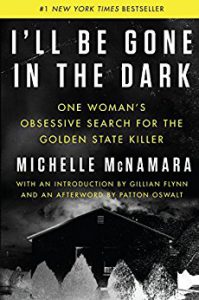

Around MFM’s inception, journalist Michelle McNamara—the genius behind True Crime Diary, passed away while working on her first, and, tragically, only book, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark—a Zodiac– or The Stranger Beside Me-esque story about the crimes of a man she dubbed the Golden State Killer. Working from the mid 1970s to the mid 1980s, the GSK was accused of murdering at least 13 people, raping more, and burglarizing over 100 homes in California. McNamara was obsessed with learning his true identity and finding justice for his victims. Although McNamara passed in April 2016, her book was finished with the help of researcher Paul Haynes and journalist Billy Jensen, as well as her husband, the comedian Patton Oswalt. It was posthumously published to much fanfare in February of 2018. In some ways, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark was already destined to be a true crime classic—it is a well written and terrifying tome that focuses on a fascinating figure, with an impressively designed cover to match—but it was cemented as one when, shockingly, a former police officer named Joseph DeAngelo was apprehended and arrested, identified as the Golden State Killer (he awaits sentencing). Karen and Georgia followed the book and the case closely.

Around MFM’s inception, journalist Michelle McNamara—the genius behind True Crime Diary, passed away while working on her first, and, tragically, only book, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark—a Zodiac– or The Stranger Beside Me-esque story about the crimes of a man she dubbed the Golden State Killer. Working from the mid 1970s to the mid 1980s, the GSK was accused of murdering at least 13 people, raping more, and burglarizing over 100 homes in California. McNamara was obsessed with learning his true identity and finding justice for his victims. Although McNamara passed in April 2016, her book was finished with the help of researcher Paul Haynes and journalist Billy Jensen, as well as her husband, the comedian Patton Oswalt. It was posthumously published to much fanfare in February of 2018. In some ways, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark was already destined to be a true crime classic—it is a well written and terrifying tome that focuses on a fascinating figure, with an impressively designed cover to match—but it was cemented as one when, shockingly, a former police officer named Joseph DeAngelo was apprehended and arrested, identified as the Golden State Killer (he awaits sentencing). Karen and Georgia followed the book and the case closely.

McNamara’s book was not solely, or even mostly, responsible for identifying DeAngelo, but detectives who worked on the case cited her unwillingness to give up as one of the reasons for his capture. She helped assure the case stayed warm. Among true crime enthusiasts and even outsiders, after the arrest of DeAngelo came a real sense that good true crime reporting could be productive, that an interest in true crime was not a pointless act of self-flagellation—a fear that many burgeoning true crime enthusiasts share. Also, it was smart and ruthless against the then-unknown GSK. The epilogue, “Letter to an Old Man,” is a biting rebuke, the last evidence of her complete disgust with him. This book is no disguised fan letter, no obsession with an evil genius. In that, McNamara shares a sensibility with Georgia and Karen of MFM. These women are first and foremost concerned with victims, and their rights, and their stories. The narratives put forth are not about the twisted, “misunderstood” men whose lives become the point of so many true crime narratives. They do not give in to tropes of victims “asking for it,” they do not blame sex workers or addicts, they illuminate their lives and ask—productively—how the crimes against them might have been stopped.

A few weeks ago, Karen and Georgia announced they were writing a book— “autobiographical self-help,” one outlet calls it. The title comes from the phrase they say at the end of every episode: “Stay Sexy, Don’t Get Murdered.” And perhaps this concept is the ethic of the new true crime I see emerging. For too long, the advice given especially to young woman was, tacitly, to avoid sexiness in any of its endless permutations: don’t wear revealing clothing, don’t spend time doing things you enjoy if those things are going to clubs or staying out late at night, don’t be too confident in yourself, don’t have sex or even suggest you might be interested in sex if you aren’t also okay with the person with whom you want to have sex committing violence against you. The list of suggestions to curb sexiness in the name of not being murdered has become so commonplace, so loudly shouted in our ears that we have become oblivious to it. But this new wave of true crime, which has risen alongside new conversations around consent, and a deeper recognition of rape culture, is doing the real work of deconstructing narratives that have been engrained in our culture for so long we’ve all ignored them.

A few weeks ago, Karen and Georgia announced they were writing a book— “autobiographical self-help,” one outlet calls it. The title comes from the phrase they say at the end of every episode: “Stay Sexy, Don’t Get Murdered.” And perhaps this concept is the ethic of the new true crime I see emerging. For too long, the advice given especially to young woman was, tacitly, to avoid sexiness in any of its endless permutations: don’t wear revealing clothing, don’t spend time doing things you enjoy if those things are going to clubs or staying out late at night, don’t be too confident in yourself, don’t have sex or even suggest you might be interested in sex if you aren’t also okay with the person with whom you want to have sex committing violence against you. The list of suggestions to curb sexiness in the name of not being murdered has become so commonplace, so loudly shouted in our ears that we have become oblivious to it. But this new wave of true crime, which has risen alongside new conversations around consent, and a deeper recognition of rape culture, is doing the real work of deconstructing narratives that have been engrained in our culture for so long we’ve all ignored them.

Project number one of MFM is to put the spotlight on the victims rather than the perpetrators of the crimes–not to blame them for their choices but to illuminate their humanity, to name their names, and to learn from their stories. And we hold on to them so tightly because we know that they’re the difference between life and death for the millions of us who know that violence against us is a terrifyingly real possibility. “Fuck politeness” is one of Karen and Georgia’s most famous catch phrases, spawning hundreds of drawings and designs festooned on bags, shirts, and pins. It is simple, crass, and feels almost specious. But its meaning is profound, and it’s hard to swallow, because it asks us to undo all our cultural conditioning, but within it we (or, okay, I) recognize an almost laughably obvious truth. How can we hold on to “kindness” as a principle when we’ve seen how many women it has, quite literally, murdered?

Ted Bundy knew to capitalize on young women’s kindness to rape and kill them, that they would be too polite to stop helping the handsome young man with the cast, too polite to scream and fight. Politeness lost them their lives. I don’t know Ann Rule’s position on profanity, but I can’t imagine she would disagree with the spirit behind Karen and Georgia’s catchphrase, because it is one of the primarily messages of the book. In some ways, Rule’s book was telling us the same things Karen and Georgia, and Michelle McNamara, and other thoughtful true crime writers and reporters are today—but we weren’t ready to listen in 1980.

And so I am grateful for the new edition of The Stranger Beside Me, because I hope it saves people from the flawed sense that the book is something less than groundbreaking art, rife with meaning and good writing and valuable insights into the human condition. It seems yet another function of society’s blindness to the real terror women face every day that Rule’s book has been disguised for so long as one not worthy of our serious attention. It’s a true crime post-publication makeover—one that has been long overdue.

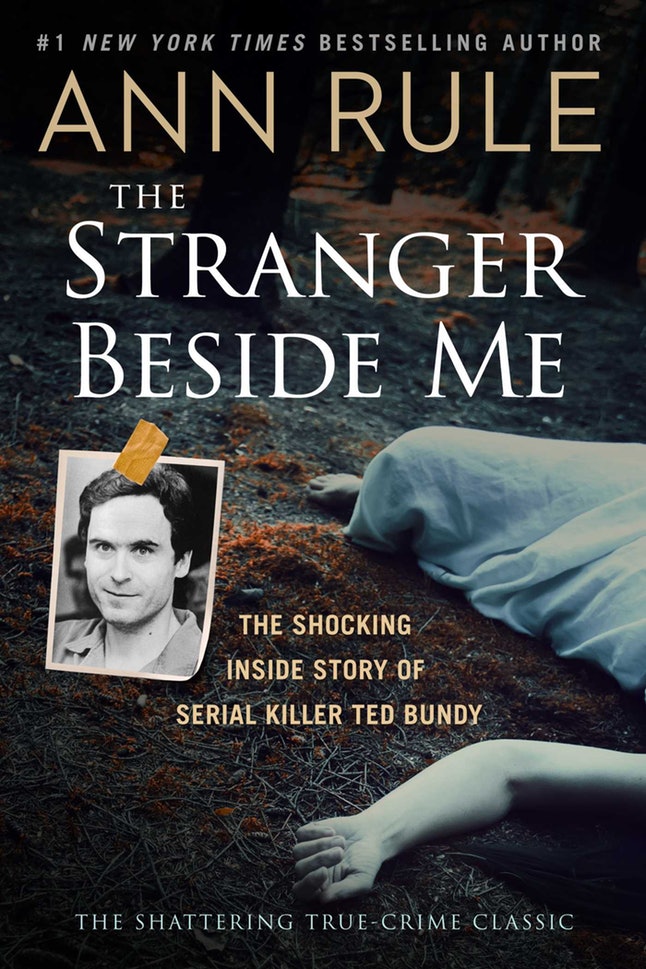

The new cover of The Stranger Beside Me isn’t particularly groundbreaking and, in fact, seems to play into some stale, gendered stereotypes. A woman in blue lies on the ground, her arm outstretched in front of her. She is dead, her face just outside the scope of the book cover. A polaroid of Bundy is taped to the murder scene image. It feels like a mystery novel, like Paula Hawkins might have written it. It does not speak much to female empowerment, to shattering stereotypes. But it does suggest that it is serious, that it is a book worthy of sharing space with its already established shelf-mates. So as a bookseller and a reader, I am happy to see this book, and true crime in general, finally being given the attention its due, but personally, I have come around to the mass market edition. Every month each of us at the bookstore chooses a staff pick. For September, I chose The Stranger Beside Me. Not one but two coworkers checked in with me to make sure I was okay with the version being mass market. This is a fair question, and one I expected them to ask. But yes, I am okay with the mass market version. Because, you know, you can’t judge a book by its cover.

The new cover of The Stranger Beside Me isn’t particularly groundbreaking and, in fact, seems to play into some stale, gendered stereotypes. A woman in blue lies on the ground, her arm outstretched in front of her. She is dead, her face just outside the scope of the book cover. A polaroid of Bundy is taped to the murder scene image. It feels like a mystery novel, like Paula Hawkins might have written it. It does not speak much to female empowerment, to shattering stereotypes. But it does suggest that it is serious, that it is a book worthy of sharing space with its already established shelf-mates. So as a bookseller and a reader, I am happy to see this book, and true crime in general, finally being given the attention its due, but personally, I have come around to the mass market edition. Every month each of us at the bookstore chooses a staff pick. For September, I chose The Stranger Beside Me. Not one but two coworkers checked in with me to make sure I was okay with the version being mass market. This is a fair question, and one I expected them to ask. But yes, I am okay with the mass market version. Because, you know, you can’t judge a book by its cover.

MARGARET GRACE MYERS is a bookseller and book reader from Maine, currently living in Brooklyn. She has an MFA in nonfiction writing from Goucher College, and a Master of Theological Studies degree from Harvard Divinity School. She has a complicated relationship with the ocean. (@margaretgmyers)

MARGARET GRACE MYERS is a bookseller and book reader from Maine, currently living in Brooklyn. She has an MFA in nonfiction writing from Goucher College, and a Master of Theological Studies degree from Harvard Divinity School. She has a complicated relationship with the ocean. (@margaretgmyers)