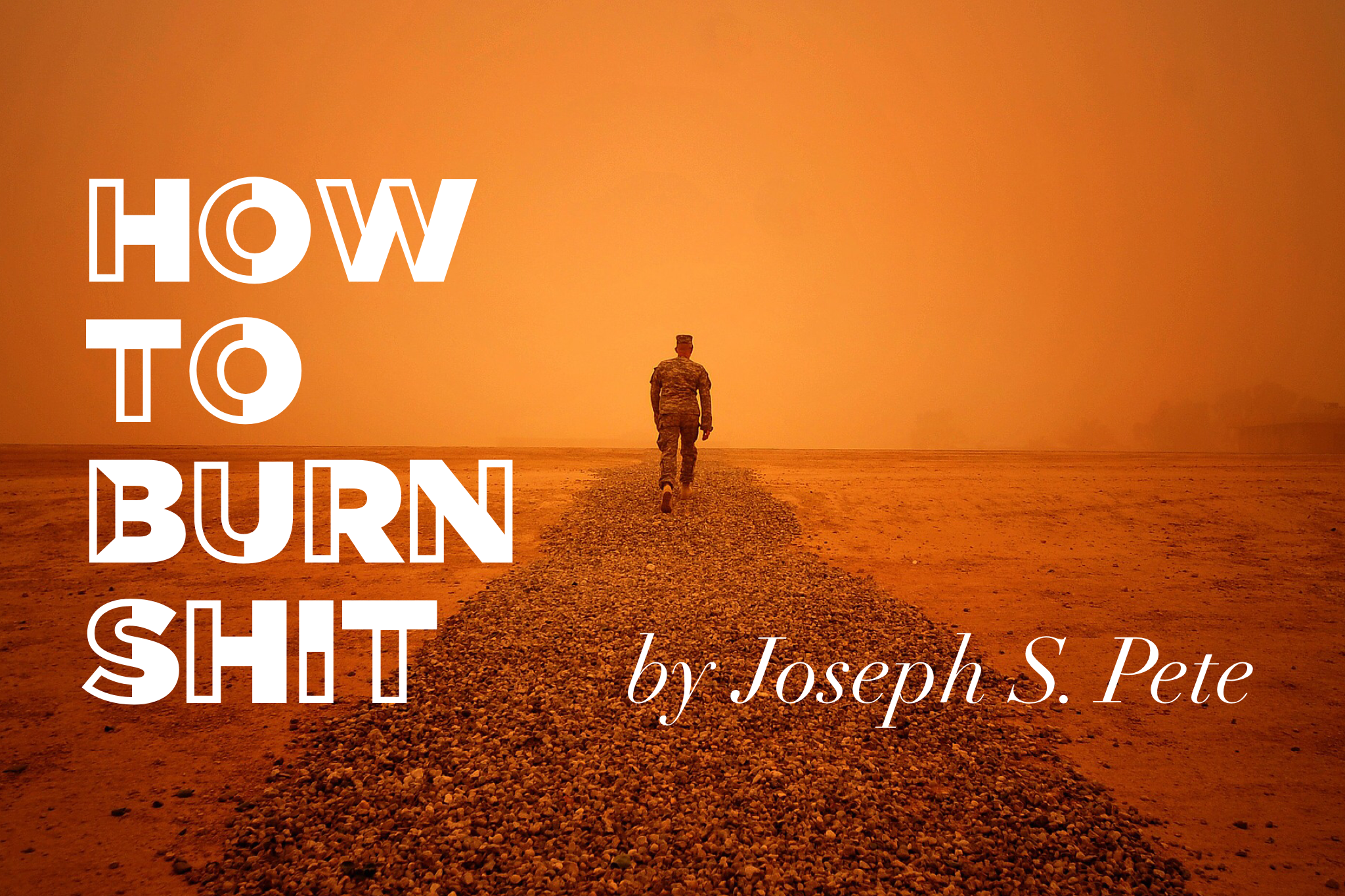

Carrie Kilman: Your prize-winning essay, “How to Burn Shit,” is set during your time as a soldier in Iraq. What came first — your identity as a writer, or your identity as a soldier? How has each influenced the other?

Carrie Kilman: Your prize-winning essay, “How to Burn Shit,” is set during your time as a soldier in Iraq. What came first — your identity as a writer, or your identity as a soldier? How has each influenced the other?

JP: My identity as a writer definitely preceded my stint as a soldier, and was partly responsible for it. As a kid who immersed himself in the sweater blanket-like refuge of books and perversely read the dictionary for fun while my mother urged me to go outside and get some sunlight and fresh air in a park, I dreamt of being a writer at an early age—first a sportswriter and then a novelist. At some point, while writing shocking exposés on weightlifting supplements for my high school newspaper, I realized I would need a day job to pay the bills and decided I’d work as a newspaperman, flexing the same writing muscles I’d need to create so-called serious literature while enjoying a regular paycheck and stability. (How wrong I was!)

When at college, I threw myself headlong into journalism, becoming an editor for and prolific contributor to the student newspaper and the college yearbook, all while also serving as an on-air news reader for the student radio station. It became an all-consuming obsession that blotted everything else out. I spent more time at city hall and the police station than on campus. When I was on campus, I was in the newsroom monitoring the scanner or scanning the wires for big national stories we might need to localize. News-hawking can be addictive: You’re plugged in all the time and convinced everything revolves around the big headlines of the nonce, and everyone else is tuned in too. I covered everything from gallery openings to women’s basketball games, from buttoned-down business ventures to mass protests over grave injustices at Peoples Park or on the courthouse lawn. I filled in as a copy editor and on the web team, sometimes pulling all-nighters and taking cat naps on the nasty leather couch in a newsroom that gestated distinguished alumni like famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle, Pulitzer laureate Thomas French, and American Horror Story auteur Ryan Murphy. In my off-time, you could find me at the anarchist bookstore, the bohemian coffee shop with all the vintage typewriters, or the other bohemian coffee shop with the fish in the bathtub. I scarcely attended class.

Eventually, my grades suffered to the point where I was no longer eligible for student loans and had no feasible way of paying tuition. The GI Bill jumped out as the only possible solution to my young, addled mind. The naive fail to realize how little they really know.

So I enlisted in the U.S. Army after 9/11. I went to war with a writer’s eye, believing it was an overarching narrative of our time when it was probably just background static for the 99 percent of the population fortunate enough not to serve in the military.

My time as a grunt in the infantry has definitely influenced my writing, but I feel that I have failed to capture the war and great cost and sacrifice and total, utter meaninglessness of it all as of yet in my writing. I must continuously strive to improve; I must find a way to atone.

CK: How long did you serve in Iraq? Your essay presents an unvartnished (and somewhat jaded) view of what it was like to serve in the military. Is this how you felt when you arrived? Or was this a feeling that evolved during your time there?

JP: Thirteen long months.

I was cynical before I enlisted and feared the worst when I initially arrived in Kuwait. I wasn’t special. Most soldiers are naturally fatalistic, given that they could die for nothing in a faraway land, given that even those who benefited likely lost more on a human level than they hypothetically gained.

You don’t enlist in the military from a position of strength and leverage. Once you’re in, you’re disposable trash they can Article 15 into a barracks room indefinitely or get randomly blown up by an IED. You sign your life away and become U.S. government property that they can dispose of how they wish.

CK: Why did you choose to submit this essay for Proximity‘s Prize Issue?

JP: I had submitted to Proximity Magazine before and gotten a form rejection for my troubles. I saw the posting for the contest and decided to go for it. You should just go for it. You might fail, but it will be even more uplifting if you succeed despite long odds.

CK: Even though it’s a flash essay, you manage to address some of the complexities of economic privilege. This appears to be a theme across your work (e.g., in your poem, “Potempkin State,” you liken your home state of Indiana to Walmart; as a business reporter, it seems you’re often more interested in impacts on workers than on business owners). Can you talk about your interest in economic privilege and why it figures prominently in your writing?

JP: I hail from one of the most heavily industrialized places on earth, where Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockerfeller became two of the ten wealthiest men in the history of the world, and where half the population lives in abject poverty today, to the point where they have to catch two buses to buy some lettuce or an eggplant. Northwest Indiana, the Region, whatever you want to call it, is filled with blue collar workers, and enough unemployed people in urban areas to wrap around a convention center and down the block during downturns. We make steel, but that business ain’t what it used to be.

Gary was a company town billed as the “City of the Century” that was largely forsaken by one of the world’s wealthiest corporations, to the point where it was routinely the murder capital of the United States during the 1990s and now hosts tens of thousands of vacant buildings, some of which look like ruins out of Ancient Rome. Our entire metro area is anchored by a company town that the once-patrician company gave up on decades ago, and where there are boarded-up and burnt-down city blocks where only a single home remains occupied.

The economically privileged have fled cities like Gary, East Chicago, Hammond, and Whiting for generic suburbs filled with strip malls and long stretches of flat emptiness. It’s been a scorched-earth progression that’s abandoned history, significant architecture, and those left behind. It’s always bothered me.

CK: You are a working journalist, but you also publish a lot of your own creative writing, too. How do you balance the two? Is there a tension between your journalism and your essay/poetry writing, or do they feel like natural halves of the same whole?

JP: The daily, deadline-driven writing of journalism serves as practice for creative writing, whether essays, humor pieces, short stories or poems. I’m a writer by day, and also a writer by night. There’s not necessarily a tension, but I have to be far more restrained in my journalism so as to not offend the sensibilities of a mass readership. I think of it as practice for the “real thing,” my literary endeavors.

CK: Where can our readers see more of your work?

JP: I’ve been widely published, in more than one hundred literary journals. Just Google me. It’s out there. There’s a lot that’s just in print and sitting on my bookshelves, but so much is online these days. I try to put good art out there that people can relate to and that means something but am not delusional enough to think that anyone is hanging on my every word. Like an anonymous screaming figure in a Francis Bacon painting, my voice ultimately dissipates into the void.

JOSEPH S. PETE is an award-winning journalist, an Iraq War veteran, an Indiana University graduate, and a frequent guest on Lakeshore Public Radio. He has done live lit on the iO Chicago stage, was a reader at the Underground Lit Fest and was named the poet laureate of Chicago BaconFest 2016–a feat that Geoffrey Chaucer chump never accomplished. His literary or photographic work has appeared or is forthcoming in New Pop Lit, The Grief Diaries, Gravel, Perch Magazine, Lit-Tapes, Synesthesia Literary Journal, Chicago Literati, Dogzplot, shufPoetry, The Roaring Muse, Prairie Winds, Blue Collar Review, Work Literary Magazine, Lumpen, Stoneboat, The Tipton Poetry Journal, Euphemism, Jenny Magazine and elsewhere. ☆ Judge Adriana Ramírez selected “How to Burn Shit” as winner of Proximity‘s 2017 Personal Essay Prize.

JOSEPH S. PETE is an award-winning journalist, an Iraq War veteran, an Indiana University graduate, and a frequent guest on Lakeshore Public Radio. He has done live lit on the iO Chicago stage, was a reader at the Underground Lit Fest and was named the poet laureate of Chicago BaconFest 2016–a feat that Geoffrey Chaucer chump never accomplished. His literary or photographic work has appeared or is forthcoming in New Pop Lit, The Grief Diaries, Gravel, Perch Magazine, Lit-Tapes, Synesthesia Literary Journal, Chicago Literati, Dogzplot, shufPoetry, The Roaring Muse, Prairie Winds, Blue Collar Review, Work Literary Magazine, Lumpen, Stoneboat, The Tipton Poetry Journal, Euphemism, Jenny Magazine and elsewhere. ☆ Judge Adriana Ramírez selected “How to Burn Shit” as winner of Proximity‘s 2017 Personal Essay Prize.

CARRIE KILMAN loves stories that explore what can divide and connect different peoples, places, and points of view. A former staff writer for Teaching Tolerance magazine and a graduate of the Salt Institute for Documentary Studies, Carrie has written extensively about social justice movements across the US. Her work has appeared in In These Times, Alternet.org, Tolerance.org, Yankee Magazine, and Wisconsin Public Radio. She currently lives in Madison, Wisconsin, with her husband, toddler, and elderly spaniel. (@cailo)

CARRIE KILMAN loves stories that explore what can divide and connect different peoples, places, and points of view. A former staff writer for Teaching Tolerance magazine and a graduate of the Salt Institute for Documentary Studies, Carrie has written extensively about social justice movements across the US. Her work has appeared in In These Times, Alternet.org, Tolerance.org, Yankee Magazine, and Wisconsin Public Radio. She currently lives in Madison, Wisconsin, with her husband, toddler, and elderly spaniel. (@cailo)