Chelsea Biondolillo bends genre rules while diving deep into her idiosyncrasies and obsessions, and The Skinned Bird is a strange, strong, and beautiful thing because of it. Reading this collection of essays was an exercise in exploration for me as a reader. Biondolillo asks poignant questions—she is excavating the “how” and “why” of both herself and human nature—but rather than give answers, she lets herself and her reader exist in the liminal space of questioning. In her exploration of how we become who we are and why we make the choices we do, she hits on universal truths all while utilizing structure to support the content of her essays. The result is brilliant; as she is at work discovering her bones, she issues an invitation to her reader: Let’s see what is underneath.

Throughout this memoir-in-essays, Biondolillo uses the interplay between the natural world and her internal world to try and better understand herself. The entire collection is organized into four parts that follow the stages of a songbird learning how to sing: The Critical Learning Period, the Silent Stage, the Subsong, and the Song Crystallization. Each section contains four or five essays, and each essay serves to illuminate sometimes direct but often indirect correlations between Biondolillo’s evolution and that of the birds she studies.

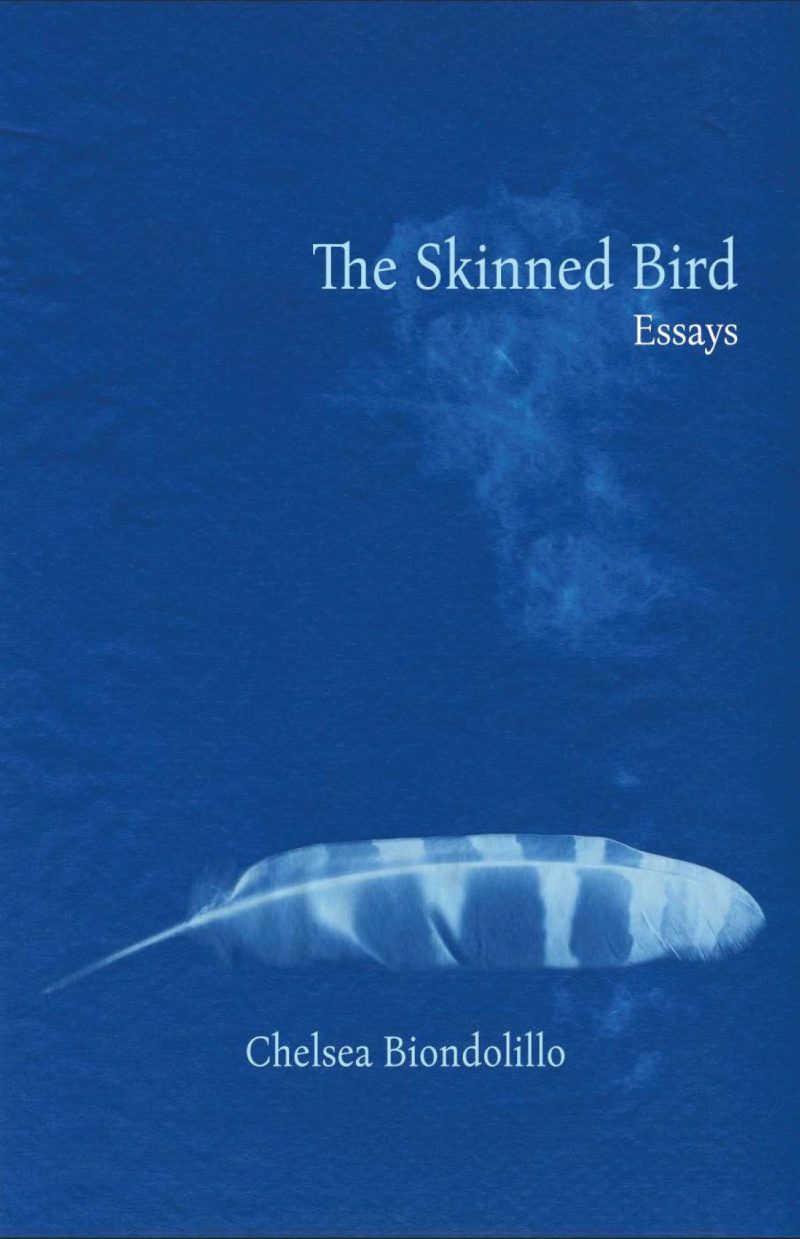

As a writer, I am always asking myself if the structure of my writing is adding to or detracting from the story I’m telling. Can structure help us see things in a different, or perhaps, more holistic, way? Biondolillo writes lyrical, fragmented essays that absorb and expound on landscape, loss, longing, and language. She writes from geological and ornithological and photographical viewpoints. Her essays include lists and footnotes and photographs and erasures and braided sections. They create a visual and artistic experience that forces the reader’s brain to make deeper and different connections; the collection as a whole is an exemplary showing of artistry.

For example, instead of writing an essay about things we say or do not say, or about the private versus the personal, or what constitutes an essay in the first place, she instead writes an entire essay in erasure form. In “The Story You Never Tell,” each page of text is superimposed underneath a near page-size photograph. There are wisps of sentences and words around the edges, but the reader never sees what is underneath.

In “Enskyment,” Biondolillo writes a number of fragments, each followed by a photograph. They are standalone snippets, but when put together they create an almost overwhelming sense of loss in childhood, though loss is rarely, if ever, directly mentioned. It’s a funky collection. She doesn’t tell us how to interpret her structure or her content, and I think that’s what creates a universal connection between her internal musings, the natural world, and her reader.

In the first section, “Critical Learning Period,” she employs clear scenes and vivid writing with little exposition. She weaves back and forth, showing how birds learn to recognize language and she posits the question of how we, as humans, are imprinted with an emotional language before we can speak words aloud. Do the things we hear and see as infants, before true memory kicks in, change the way we operate moving forward? How do we learn to love, to cope, to shield? We return to this through-line again and again in each section as Biondolillo studies her relationships with her father and her ex-husband.

There is an excruciating physicality in The Skinned Bird. That physicality at times made me squeamish, but it also made me want to dig deeper. In “Bone,” I could feel the voicebox-less vultures holding down my arms and legs with their talons and using their beaks to rip away my flesh; what lies underneath. In “How to Skin a Bird,” I could feel myself using my fingers to roll back skin and access the bones of the underlying wings; what lies underneath. In “Enskyment,” I felt myself moving back in time, looking at the creatures and deaths in my past, the ones I saw and felt and buried deep inside me; what lies underneath.

While The Skinned Bird isn’t lengthy, it is deep and open. It can be read in one giant gulp, infusing the brain with imagery and wonderings and sorrow and hope. It can be parsed out, section by section, letting the brain create new synapses between the form and the words and the big “T” or little “t” truths. I personally took my time, reading one or two essays per sitting, thinking about how Biondolillo was able to create forward movement with her writing.

At the end of the collection of essays, I see these truths: We are all looking for (or running from) home; we are all trying to protect ourselves but sometimes hurt ourselves in that process; we are all impacted by the world around us, whether that’s our familial world, the natural world, or the relational world. Biondolillo writes, “I am looking for a way to get at the experience of a thing, the memory of it, to better understand the meaning of it. I am expecting the process to be messy.” We are searching and discovering what lies beneath, what our bones look like. It is a messy process; The Skinned Bird excels at existing in that space and creates new ways of seeing and making. I’m glad to have it on my bookshelf.