Nicholas Casey’s parents met on Diego Garcia, a small wisp of beach and coral snaked around a lagoon in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Each was a sailor on a different cargo ship, his mother an “ordinary seaman,” his father an engineer. The couple spent one night together, forced by a storm to share quarters on the latter’s ship. Nine months later, when Nicholas was born, his mother sent word to the wayward sailor and the two met back in California. Nicholas’ father would continue to set sail for seven years, returning for short visits that both animated and punctuated the boy’s childhood. And then he vanished, fleeing an alleged murder—or so Nicholas thought. Nicholas grew up with confusing and conflicting accounts of who his father was and, in-turn, who he was as well. This would last twenty-six years.

Casey’s New York Times Magazine essay, “Finding my Father,” is a rumination on the power of knowing. As a journalist and New York Times bureau chief, Casey is no stranger to gathering facts, reporting, and research. “When I write a reported piece,” Casey told me in a recent interview, “I’m reporting on as close as I can to what happened. Part of it has to do with the fact that you can get closer to what happened when it’s recent. There’s a lot more things leftover. The memories are more fresh. There might be receipts. There might be pictures on people’s phones.”

However, when writing the story of his own life and the role his father’s sudden disappearance played in it, Casey only had memories to work with. The problem? As he explains it, “The more time that passes, the more memories completely diverge. Each time someone tells a story, it changes how they remember it. So, two people telling the story at different situations to other people, they’re very fast diverting from like a common point of some memory that they shared.”

How Casey’s parents met, how he was conceived, why his father left when his son was only seven years old—all these memories had diverged into family lore and myths. When a genealogy DNA test turned up an unknown relative and allowed for the rapid reconnection to his father, Nicholas Casey began to gather facts. The result is a narrative built on what Casey knew to be true, the myths he and his mother shared, and a journey towards clarity.

Brandon Arvesen: How long had you wanted to write this story?

Nicholas Casey: I’ve been thinking about iterations of this story for years. Even before I actually found where my dad was. I was really interested in the story of how my mother and father met to begin with on this place I’ve never been to, Diego Garcia. So, I would say there’s been at least seven or eight years that I’ve been interested in writing something about what I knew about my father. And then, of course, that changed quite a bit in 2017 / 2018 when I actually found him and met him. I had proposed writing a magazine article not long after that. The proposal was very similar to what we used to propose New York Times Magazine when we did it this year. But I think the reason why I didn’t end up actually writing it then was because I realized that there was a lot missing to the story. I’d just found him. So, I didn’t know him that well at that point. I think, for something like this, I needed not only to sit on his story and my own feelings about it, but also to allow our relationship to actually start to develop before there was really something to say about it.

BA: At what point did you feel that you had a professional or emotional space to actually sit down and write this story?

NC: I think it was probably about a year into knowing him, although I didn’t necessarily write it after a year. Definitely after I had gotten down to Los Angeles and met him. I saw him again when he had moved to Florida for a period of time. I saw him just before the pandemic. I felt after about a year, the conversations that we’d had over the phone, that it was time. But I still waited a little longer than that to get down to doing the work.

BA: And where did you start?

NC: Being a journalist, I’m trained to write things chronologically. The first, draft of this started with my mom and this photo album that we had of Diego Garcia and of her meeting my dad. It really started just with a story of how the two met. And it was one take into it that my editor said, “Well, actually, I liked this part, but I’d really like to see in the beginning: just this image of what a kind of unusual moment it was for your dad to show up and what that was like for you as a kid.” And that became the start of the piece before it goes into the backstory.

BA: How did you craft that moment? Was that all just memory or did you interview and research to really get the finer details?

NC: I just wrote it down based off of purely what I remembered. The first drafts of writing this largely had to do (almost entirely) of writing out what I remembered as it was. But, a lot of this piece we revisited during the fact-checking process. We had a fact-checker because this is a magazine article, and the fact-checker went back to my mom and my dad. One of the things that I found fascinating about this process was not just the things that were different from how they remembered them, but how we reconcile that. There were other bits, especially in this part about how my mother and father met. I found when they were being approached by a fact-checker, as opposed to just telling the story to me, they were a lot more precise about all of the details. Especially when they were not asked to tell a story, but as: “Well, is this what happened? Is this exactly what happened? Is this the name of that?” It gave them a precision that they don’t usually have when they’re narrating things off the cuff, as they did many times to me.

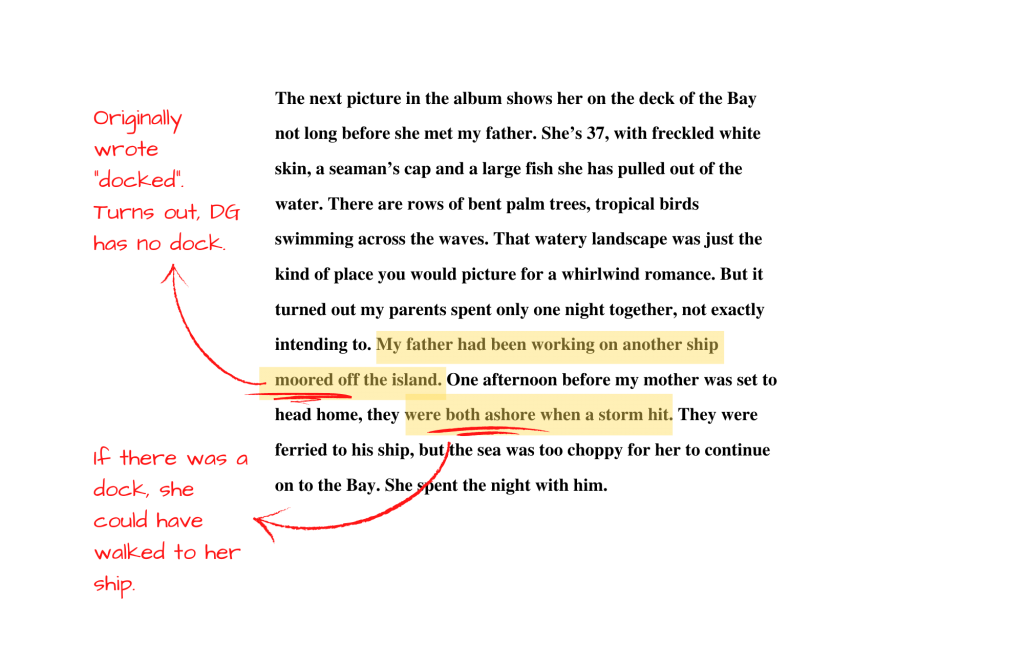

NC: So, one example: I’d written that my mother’s boat was “docked” in Diego Garcia. And when the fact-checker came, she said, “No, the boat wasn’t ‘docked.’ It was ‘moored.’ There’s no dock in Diego Garcia. You just have to put the boat in the lagoon. There’s no pier that she would walk out to.” And it was those sorts of things, I think, as she told the story, she wasn’t so precise about “moored” versus “docked.” But yes, when you can come back to it in the context fact-checking, we’re not just telling stories anymore. You get another layer of precision. I don’t think that necessarily shows up in people’s memories when they’re just talking.

BA: And what an interesting example because, if the boat was “docked,” then nothing was stopping her from getting back to where she needed to be.

NC: Exactly. The plot holes are starting to become clear and that’s when I think research, even if it’s just going to someone and saying, “Think very carefully about what this was” can yield quite a bit.

BA: How close do you think—through interviews that you’ve done, the narratives that you heard growing up, and the fact-checking process—have you gotten to the entry point of all those divergent memories?

NC: Well, I think we’ve gotten close because it was not just my mom, father, and me. My mom and I were together a lot of this time. So, as we told the stories to each other, I think those probably converged. Having my dad’s memory of certain events was very helpful because he was the one that was isolated. He was the witness that wasn’t talking to the other witnesses all these other years. And there were many points in the story where… I’ll give you another example.

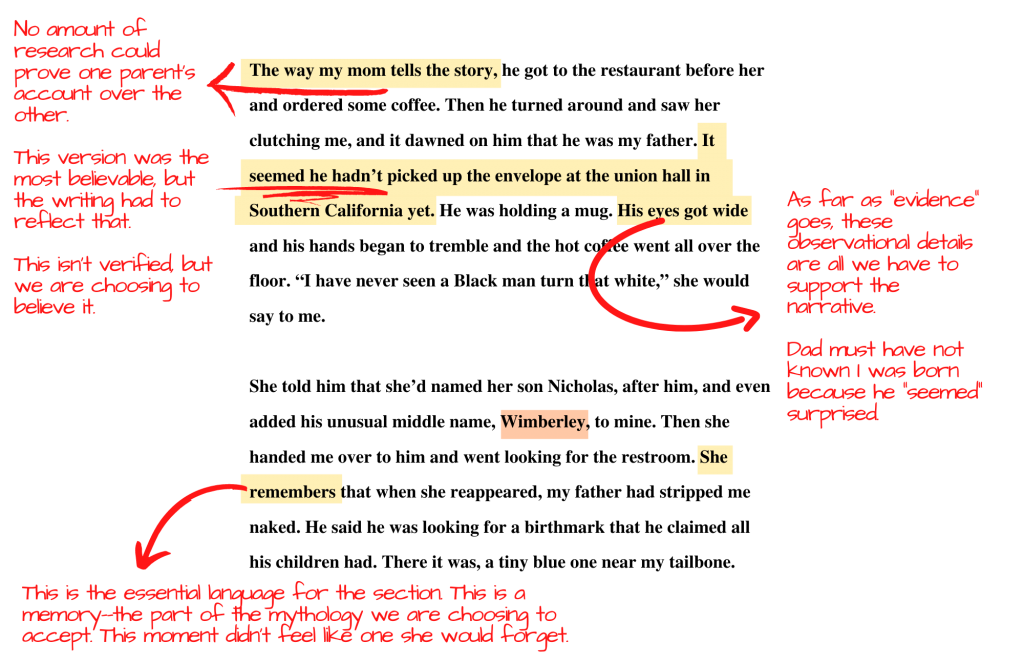

In that section my mom says that she sent a birth announcement to my dad and that he didn’t get it. And the reason she’d known that he didn’t get it was because he was shocked when he saw me. When we were fact-checking, my dad said that he actually knew that I was born and that this wasn’t a surprise to him and that he probably got it. But the way that he was speaking about this, we could tell there were some holes in his memory. And part of this probably was that he didn’t want to admit this, or he’d later told himself that he actually knew. And I very much trusted my mom’s version more because I think the mother’s not going to forget something like that, whereas I think dads can. But still, in writing this, we had to change the language of it to “The way that she tells the story, this is what happened.” Earlier drafts of it just narrated this as though this was a commonly agreed narrative here, which it wasn’t. There were some disagreements on that.

BA: Obviously both of your parents were involved in the creation of this piece; they must have known you were writing something about it, right?

NC: Oh yeah. I told them really early on that I was going to write about them and I told my father I was going to write about him. I also came to LA to see him a bit more, and some of that (as you saw) is in the piece. We took pictures and stuff. He was very aware that this was a project, but I will say that it really wasn’t until the fact-checking process that he became fully aware of what the nature of this kind of work was. This fact-checking process, which was toward the end, was really grounded in research and trying to figure out… it’s the research in terms of reconciling stories.At one point the fact checker asked him if he had shot someone and if he had been sent to jail for 30 days and given three months of probation. And he said he didn’t want that to appear in the story. I had to explain to him that the story wasn’t about that he killed somebody. It was about us, but in order to be a story about us, we couldn’t ignore one of the central facts: he vanished. And just before he vanished, he’d said that he shot someone, and my mother and I had no other choice but to think that this is why he’d vanished. Either he’d run away from the law or I thought, more likely, he probably died in prison. And it took him some time to kind of understand that because he’s not a journalist, obviously. I don’t think he’s ever done an interview with one, and especially not for a profile where they’re digging into your life. But I did really have to kind of panel him the same way as I’d deal with a reluctant source near publication time. I’ve explained to them that this is just the nature of the job and what we’re doing, and that it’s not going to be worth anything if it’s not true. And he eventually agreed with that. But that was a little hard when he realized that some of his history—his rap sheet—was going to be published in public.

BA: Did you corroborate that in any way outside of the interview?

NC: Yeah, we did. We got the documents. There were documents showing that he had a felony conviction. It was during the same dates that he’d said. It’s very unusual, obviously, for a source, regardless of whether it’s your dad, to say that they committed a crime that they didn’t. But anytime, at least in my world, when a crime is mentioned you’ve got to triple check that because there’s always a record of it. So, the fact checker and I did find the record for it. With that, we were satisfied between what he said and what the record said. That was an important thing that we wanted to make sure had actually happened. That this wasn’t just some story that he had told us, that he was still holding on to. This was also something that everybody in the family knew about because this was a huge thing once it happened. So, it wasn’t just coming from him back then and him now, but it was also coming from other family members and we could also see it in records.

BA: When you’ve got that overwhelming evidence, you’ve got his story that he’s told you, and you’ve got a resistance to include it in the piece, what do you do to navigate how much of it you’re going to share?

NC: It would be different if he were someone that I didn’t know. It would be different if this incident weren’t the reason that he disappeared from my life, but to some degree I felt that because of the decision that he made afterward to disappear, the least that was required was an admission that it had happened. And of what had happened there’s certain things that you have to weigh, you know? Was he someone so young, like in their twenties, that if this had been in the paper it would ruin their reputation for years? Well, that’s not the case; this happened a long time ago. Could he get fired from work because of this coming out? Well, he was retired. We couldn’t see, the editor or me, any negative consequences of this being published. Any negative consequences other than maybe his feelings being hurt. But, you know, a lot of feelings have been hurt in this family and I think this was the least of them. And, in fact, he was really happy when the story came out. Ultimately, I think the important part in a case like that, to navigate it, as you asked, is not that you include less, but that you explain more why you need to include what you’re including.

BA: In the essay, you write about discovering your father’s alive and say, “I thought about how strangely simple, the detective work turned out to be.” I’d love it if you could talk about that a little bit.

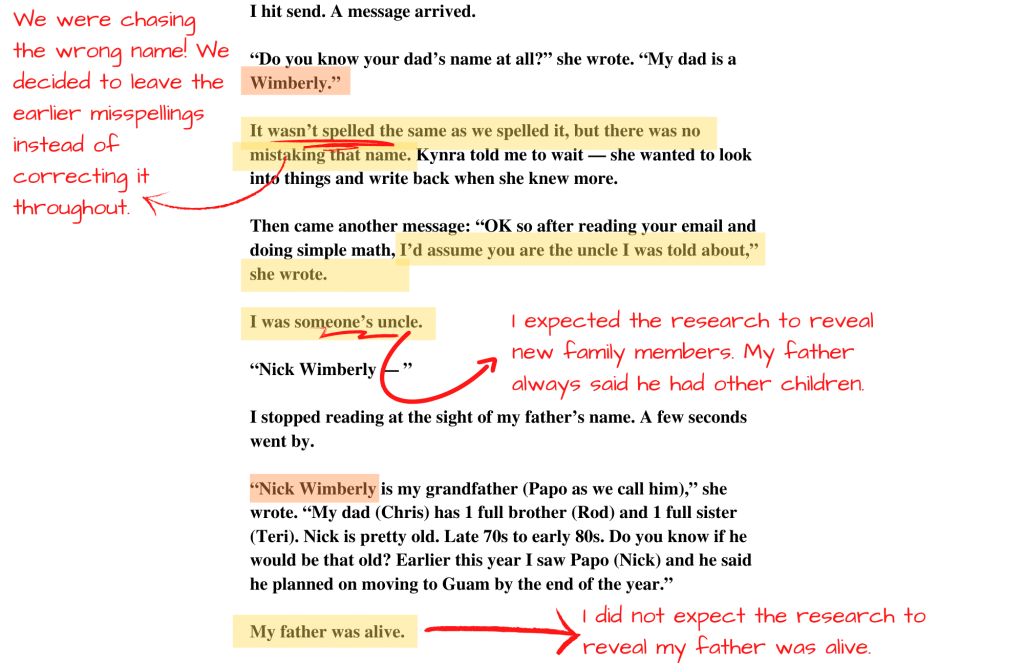

NC: I always wanted there to be a word for the kind of mystery or puzzle or answer that you couldn’t get until you’d actually given up. This felt like one of them, basically. Actually, trying to force that door open never really yielded anything. Only until I’d given up on finding an answer that I just had to literally wait for it to drop in my lap suddenly. I’ve heard of people hiring private detectives to find family members, going through genealogies and histories and it was just… It did feel very strange for the answer just to just pop out in a very random way over the course of an afternoon.

BA: In that moment, did you recognize the magnitude of what was about to happen with that one piece of information?

NC: I actually thought my dad was dead at that point and I didn’t think [the DNA test] was going to lead to my dad. I was very happy to have found [more family] because I was going to be able to meet her. I thought, “I’ll probably be able to meet a couple of my dad’s other children and maybe some nieces and nephews.” I didn’t think it was going to lead to him because of his age and his past—between being on a boat and being in prison. So, no, I didn’t. It really didn’t click for me that I was going to find him until she mentioned him. I’d set the idea aside, assuming that I wasn’t going to find him. And then of course she said that she’d just seen him, then of course I knew.

BA: Is there a moment in this essay as it stands that you would say was most shaped by the research process?

NC: I would say the part that got affected most—especially during the fact-checking process that we did—was the section that starts with: “My father stayed for no more than a few days” up until “30 days passed.” It was the section that was the furthest in the past. I showed this to a friend of mine, an earlier draft of it, and in the second paragraph where it says, “The book began with a postcard of a satellite image taken from miles above an inky sea.” It originally said, “The book started with a satellite image.” That’s what I remembered. And my friend asked me, “Well, how did your mom have a satellite picture of Diego Garcia?” So, I actually went to the photo album thinking, That’s a great question, because I remembered the satellite picture. And I pulled it out and I say, “Oh, this was a postcard.” I’d been looking at this picture my entire life. I had no idea what it was. I just saw that it was a satellite image. I had thought, somehow she’d gotten some satellite image because there was a military base [on the island], but it wasn’t; it was a postcard. These pictures were still around. So I went and looked for these pictures again. Another thing here. So, an earlier draft had said that my dad had pulled out a flask and I remember seeing that he had a flask, but when I spoke to my half-sister Tosha, I was telling her about it. “He used to drink all this rum out of a flask.” And she was like, “No, no, he never had a flask. He had a tiny glass bottle and that’s what had the rum.” He was like getting rum out of these little bottles that you’d get at hotels or. And I swear, I remember as a kid seeing a flask, but I didn’t know what a flask was. So, I probably changed that in my head. I knew he was drinking something out of a small drinking vessel that wasn’t a full-size bottle, and it wasn’t a cup either. So, we changed that. He also said, “No, no, I never had a flask.” He’s just not organized in his drinking enough to have bought a flask that had like his name engraved on it. He just drinks whatever he buys in the liquor store and they don’t have flasks there. So that was something that we went into. We’ve got to call it a tiny glass bottle, not a flask. It’s always referred to as a tiny glass bottle throughout. You’re never going to be able to (when something is that old) be able to get to the bottom of everything. But sometimes there will be little details that you will find; these consensuses over multiple people and then you know that that’s something, even if there’s no document that’s there. The challenge of this was there’s just not a lot of documents. This is not a family with big family pictures. I don’t have a single picture of him, my mom, and me together. We don’t have camcorder videos from the 1990s. He has no record of hardly any of these things that happened, whatsoever. So, all it is is what these people remember. But there are ways, I think, to triangulate and figure out how to reconcile these differences in memory.

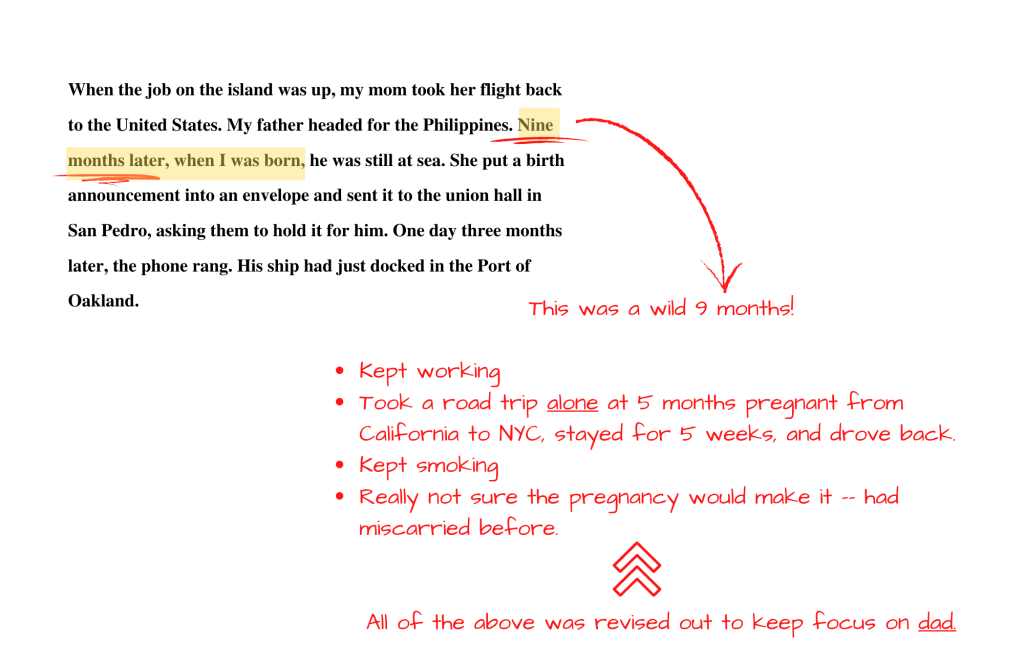

BA: We jump a lot in time. For example, you write “Nine months later when I was born.” I’m wondering if you had a lot of interview material with your mom about what those nine months were for her? Did you gather things that you decided to not include?

NC: Yeah, quite a bit. It was in an earlier draft and I, I can’t actually tell you why it’s not in this one either because they gave me even more space than I ended up using. There was a lot that wasn’t here. I think I was having trouble figuring out how these parts fit in. I think the reason I actually cut it was because ultimately, I just had to make the decision that this was going to be primarily about my dad and not about her, [my mom].

What she told me was that she had had several miscarriages during her first marriage. And she’d been told that she wasn’t going to have children anymore. So, she knew that this was going to be her last chance, and she wanted to be a mom. I think there was a time when she was thinking about whether she should just have an abortion or not, but decided that if she did, then she probably wouldn’t get this chance ever again. Even if it would mean leaving the boats. At the same time, because she’d had these miscarriages in the past, she was extremely skeptical that I was going to be born at all. So, she didn’t quit working on the ships. She stopped working at sea, but she kept doing training programs thinking that she was going to probably be at sea sometime in the next year or two. At one point, she took a road trip by herself when she was six or seven months pregnant from California to New York in the winter. I think she was five months pregnant, she told me, I’d have to look back. Then stayed in New York for probably five weeks, a little more than a month or so, and then drove back. She told me she didn’t stop smoking until it was seven or eight months into the pregnancy. She really was kind of treating the pregnancy like it was not something that she was counting on actually happening. And then it did. There was actually a passage about that, that I ended up taking away. I found out what was going on in in her mind in those nine months.

BA: You almost have a whole second essay right there.

NC: I was born in ‘84. America as a society was still getting used to both the idea of interracial kids and marriages, and also getting used to the idea of single mothers… Dan Quayle, who was the Vice President at the time, said something like, “Murphy Brown shouldn’t be a single mom. That’s not a message we should be sending to American families as being ‘okay.’” Those were the kinds of conversations that were going on in America at the time. And a lot of the messages and the emails I got after the story, the most common question I was asked was, “Where was the story of your mother here?” And I think I really needed to, for a magazine story, focus on one aspect. And the easiest really was to focus on my dad largely because there was just so little information.

BA: What part of your research do you think needs to be front and center in this conversation?

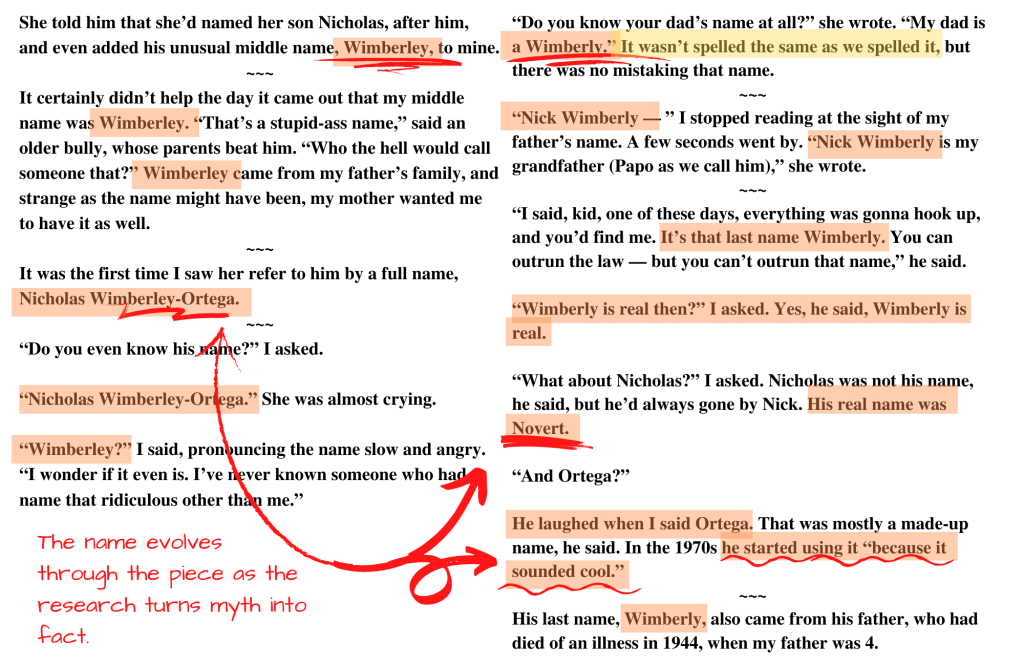

NC: Not anything major, but one thing that I might point out is that we had to make a decision on what we were going to say my dad’s name was. And we spell his name wrong in the first references to “Wimberley” including the references to my name. I actually don’t correct it until I find out that his name is spelled differently than we spelled it. That was a decision that we had to make because, well, his name isn’t spelled “Wimberley,” but this was the name we were chasing. And there’s the point where we refer to him by a full name, Nicholas Wimberley Ortega. And that wasn’t his name. So, there were some decisions that we had to make including bits of information that weren’t true [even if we initially] thought they were true. Correcting them to say, “Actually his name was Novert, it wasn’t Nicholas.” I think if this were a straight up newspaper article, we wouldn’t be able to tell the story through my own perspective that way—when the perspective wasn’t right. We would have had to correct it in some way. And I think that’s the advantage of the kind of storytelling that’s happening here.

NICHOLAS CASEY (@caseysjournal) is the Madrid bureau chief at The New York Times, covering Spain, Portugal and Morocco. Over the last decade he was stationed in Colombia, Venezuela, Israel, Mexico and the U.S., where he covered the 2020 election. In 2016, he won the George Polk for his work in Venezuela.

Previously, Casey worked at The Wall Street Journal from 2007 to 2015, where he held many roles. He started as a retail reporter in Los Angeles before moving to Mexico City to cover the fight between the government and the drug cartels. He then led the paper’s coverage of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which included the last Gaza War. Casey’s reporting has also won the New York Press Club Award, the Clarion Award and honorable mention from the Society of Publishers in Asia.