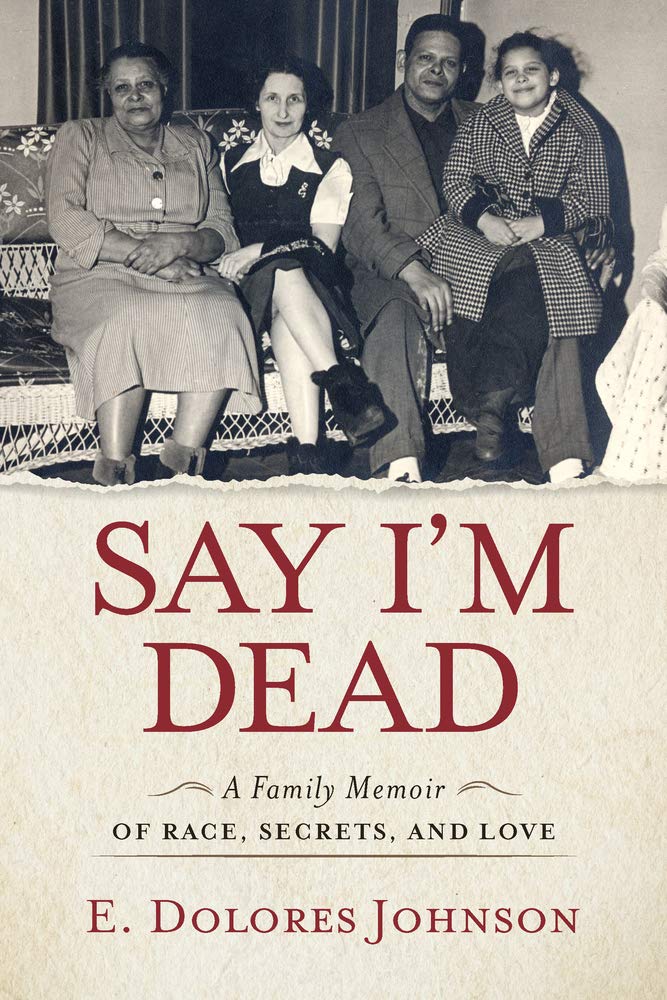

E. Dolores Johnson is an essayist, memoirist, and former tech executive who consulted with universities and corporations on diversity and inclusion. Her debut book, Say I’m Dead: A Family Memoir of Race, Secrets and Love, was published by Chicago Review Press in June 2020. In the last year, her memoir won the National Association of Black Journalists’ Outstanding Literary Award, received a starred review from Booklist (American Library Association), was included on Powell’s Black Lives Matter Reading List, and was cited in Publisher’s Weekly as providing a bounce for small press sales during the Spring 2020 market.

Johnson and Sonya Lea, author of Wondering Who You Are, first met at the Tin House Summer Workshop, where Dolores was writing Say I’m Dead, and Sonya was writing essays on whiteness and racism in relationship to the last public execution in America, a legal lynching in her hometown in Kentucky.

Over the past year, the two connected again to discuss Johnson’s memoir.

Sonya Lea: In 1943, your Black father and white mother were terrified by a local lynching and the mandatory prison time exacted for violating Indiana’s anti-miscegenation laws. So they fled, married, then lived in hiding for decades. Your parents chose love over the law 24 years before Loving vs. Virginia’s 1967 win at the Supreme Court. You woke up to the absence of your mother’s family after you began your father’s genealogical search, in your adulthood. How did hearing your parent’s story impact you? Were parts of their story closed to you?

E. Dolores Johnson: We lived with no mention or knowledge of my mother’s white family for 36 years. They simply did not exist in our consciousness. It seemed normal and sufficient that we had a (Black) family. Until I caught the roots craze and did my father’s genealogy. Once I stood back from the resulting large chart of generations of relatives, it struck me that the only white person there was my mother. That could not be right. Where were the branches on her family tree?

Only by confronting my parents in an emotional family weekend did they finally tell me, at age 31, that they ran away and disappeared without ever contacting her family again. And they were still afraid, 36 years later, that the law would come after them. My identity as a Black woman tilted, hearing about the family she left behind, realizing my white half had never been acknowledged. I had to know what that meant in me.

SL: You begin the book with a detailed description of the emotions you experienced while being required to code-switch to accommodate whiteness and white work environments. You interrogate yourself thoroughly on the page, noting: “The thing was, leaning into white culture had gotten to a point where I wondered if maybe I was selling out. Like fitting in and enjoying the other side diluted the Blackness that always defined me. I had to get out of this halfway house and get back to me. But how?” Was writing this story one of the ways you authenticated this experience? What was the moment you knew you were going to write this book?

EDJ: For me, writing memoir means honestly examining significant happenings that provoke changes in your life. The theme of identity is key to Say I’m Dead, for me and other family members. Performing behaviors acceptable to white people was exhausting, having to filter out my natural speech and body expressions. This is something very familiar to Black people who work in white environments, something whites don’t realize or ever have to do themselves. This is the authentic truth and writing Say I’m Dead was not necessarily a reckoning of this truth as much as an explanation for white readers.

I once worked at a journalism institute, where I picked up on ways to document stories. In talking with one journalist about my background, she agreed to interview my mom on tape when she was in her 90’s, to capture her story in her own words. Considering that recording was the moment I started writing this book.

What do you mean by “authenticating experience?”

SL: That’s what I think of as the writing process getting close to the lived experience. Or of the craft used to convey the experience

is as close to the quality of the experience possible. When I was writing my memoir, and when I sent it into the world, I had a sense of trying really hard to convey how beautiful it was to live in my relationship with my husband, though there were these tragic and difficult moments. But perhaps I should say that I wanted to write the relationship as complicated as it was. I’m thinking here of what Maggie Nelson talks about when she says, “I like to think that what literature can do that op-ed pieces and other communications don’t do is describe felt experience…the flickering, bewildered places that people actually inhabit.” And so I’m asking how the process of writing the scenes, of finding the language, of detailing the emotional and lived truth might have been a way of getting to the reality of this complex story?

EDJ: I worked to put the truest representations and feelings of my and my family’s lived experiences on the page. It was an effort to tell the unvarnished truth so the reader got an authentic understanding. It wasn’t as much a craft technique as it was my tendency to very direct language and the need for the reader to stand in my shoes.

SL: The story of investigating your mother’s family, the white mother who had to escape the systemic racism of her hometown in order to be with the man she loved, became one of the ways you sought the truth. This was incredibly powerful in Say I’m Dead because your mother had created a way of leaving that included making her family presume she was dead. Why do you think you were the one to do this work?

EDJ: When my mother finally told me her story the first time, she raised her chin a bit defiantly and said, “I left my family and never meant for them to find me. And they never did.” It was mind blowing, trying to come to terms with what she had done. Not only was it necessary to channel her emotions, the love, the anxiety, the fear, the sorrow she had in leaving behind a family that loved her, but it took a lot of research to understand the conditions in Indiana at that time. The record showed what my parents told me: it was too dangerous to be with the man she wanted to have a family with. There had been a lynching of two Black men in Indiana, partially because a white woman claimed rape, and after they were dead, she said it never happened. In 1943, openly affiliated Klan members sat on the Indianapolis city council, who would have readily enforced the prison time for her crossing the race line.

You ask why I was the one to do this work. Some would say I was the risk taker in my family, the first to go to college, the one to break corporate ceilings, the one to move to Europe. My older brothers chose different paths – one a committed race man who dedicated his life to teaching inner city kids, the other living a low-key life with a white wife on the white side of town. Neither of them felt the same pressure I did from the daily shift of my identity from privately Black-centered to white corporate work. I had to clarify for myself what the dual heritage meant to my identity, while they felt more settled in who they were.

SL: Considering the stance of your mother – you say she “never had the woe‑is‑me talk about mixed‑race prejudice. Instead, she modeled how to let such “foolishness” roll off our backs as best we could.” Did speaking about the mixed-race prejudice in the book break any family codes?

EDJ: My family all understood mixed-race prejudice because we lived with it every day. People called us names, said insulting things, recoiled in horror at the site of us together. Beat up my brother for looking too white, caused my mother to hide her husband’s race to keep her job, and so much more. In 1958 when my parents had been married for 15 years and I was 10, PEW Research did a national poll and discovered that 96% of Americans thought race mixing was wrong.

Yet, my mother was concerned most about what we ourselves thought. We were a well-knit family who looked out for each other. We did not have any issues of our own about being mixed race. It was other people who could not understand that people of all races were the same in their desires, needs and spirits. What Mama did was treat and accept everyone the same and show us how not to take society’s racism into our own hearts.

SL: In your memoir, there are also terrifying stories of the racial violence you endured, including when white people threatened your life. You were born in 1948, and throughout your life, you endured many racist roadblocks and aggressions. You lived for a time in Louisiana, where you had a cross burned on your lawn. As an adult, when you searched your father’s genealogy, you found out that your grandmother was the product of a plantation rape. You and your family lived the changes our country continues to wrestle with, and which are so very apparent in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, and previously in Ferguson.

It’s such an impactful story you’ve told here, including the ways the police interacted with your family, and the ways that influenced you as a child. You say, after one encounter with your family stopped by a police officer: “The police had rendered my powerful father a timid subservient in front of us, because he had a white woman. They disrespected Mama for having a Black man, skipping any normal courtesies given white women. Because she was only a sort‑of white woman.” You’ve also included your daughter and grandchild as the next generation in this memoir, including the ways they must deal with the resurgent bigotry of this time. I know you were active in the Civil Rights Movement in the sixties, and I’m curious about how you see what’s taking shape now, for your family and the community. Do you envision your writing and community as continuing the work of your ancestors in fighting for collective freedom?

EDJ: The historic sweep of racism’s impact on five generations of my family was an intentional story arc for Say I’m Dead. The theme of how racism has impacted us in so many forms from 1890 when my great grandmother suffered multiple plantation rapes to my parent’s secret marriage during Jim Crow, my troubled need to understand my mixed identity and my daughter’s fears today about her son’s possible police encounters is meant to illustrate how deeply seated racism is and always has been in America.

The racial protests following George Floyd’s death erupted from another historic thread. White authorities have abused Black bodies without consequences dating back to slavery beatings and continuing on to stop and frisk ordinances and today’s vigilante and police killings. On so many fronts, in housing, education, employment, economics and income the racial disparities continue to plague our country. There is much work to do in the fight for true equality and freedom, and people, Black and white, have got to keep up the fight. My own intention is to keep writing works that give Americans insight on what it’s like to live on the Black side of the line.

E. Dolores Johnson’s debut book, Say I’m Dead, A Family Memoir of Race, Secrets and Love, was published by Chicago Review Press in June 2020. Her essays have appeared in Narratively, the Buffalo News, Hippocampus, Pangyrus, Lunch Ticket, and elsewhere. Johnson completed Grub Street’s year-long MFA-equivalent Memoir Incubator, and attended summer writing conferences at Bread Loaf, Voices of Our Nation, and Tin House. She was awarded writing residencies at VCCA, Blue Mountain Center, Ragdale and Djerassi. Johnson is a former tech executive who has consulted with universities and corporations on diversity and inclusion. She holds a BA from Howard University and an MBA from Harvard University Graduate School of Business. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. (@e_dolores_j)

Sonya Lea’s memoir Wondering Who You Are (Tin House) about what happened after her husband lost the memory of their life, was a finalist for the Washington State Book Award, and won Seattle’s Artists Trust Award. Wondering has won awards and garnered praise in a number of publications including Oprah Magazine, People, and the BBC, who named it a “top ten book.” Her essays have appeared in Salon, The Southern Review, Brevity, Guernica, Ms. Magazine, Good Housekeeping, The Prentice Hall College Reader, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Rumpus, and more. Lea has worked as a house cleaner, a cook, an editor, and for museums and science centers. She creates retreats and teaches writing in North America. (@sonya_lea)