I first experienced Hanif Abdurraqib’s writing later than I should have: a 2016 essay at MTV News published in the wake of Prince’s death. Abdurraqib revisits Prince leading a marching band through the rain of the Superbowl Halftime Show in 2007 in Miami, Florida. I loved that moment. We all watched it unfold: Prince playing through “Let’s Go Crazy” and “Baby I’m A Star” and a cover of “Best of You” and “Purple Rain” and the explosion of guitar. I don’t remember who was playing in the game, only the brief window of music.

In They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, Abdurraib writes across music, but also about genres, landscapes and locations (Terminal 5 in New York, Columbus, Ohio, Chicago), time, joy, sorrow, and confusion. He describes the beginning a Carly Rae Jepsen concert: “The feeling barrels towards you as the lights go down…”; remembers a friend at a Fall Out Boy concert: “No one decides when the people we love are actually gone”; and sees Prince performing “on a stage slick with rain, walking on actual water… Dearly beloved, when the sky opens up, anywhere, I will think of how Prince made a storm bend to his will. How the rain never touches those who it knows were sent into it for a higher purpose… I will walk into the next storm and leave my umbrella hanging on the door.”

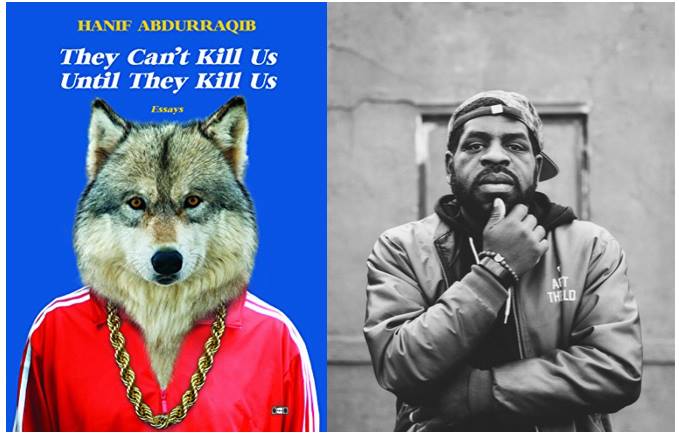

Hanif Abdurraqib is a poet, essayist, and cultural critic whose writing has been published in Muzzle, Vinly, PEN American, New York Times, and elsewhere. His first full length poetry collection, The Crown Ain’t Worth Much, was published in 2016 and was named a finalist for the Hurston / Wright Award for Poetry.

Contributor David Cotrone interviewed Hanif Abdurraqib using the acknowledgements pages of They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us as his guide.

In They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, you write about The Weeknd, Fall Out Boy, Prince, Carly Rae Jepsen, Bruce Springsteen, Nina Simone, Johnny Cash, Chance the Rapper, My Chemical Romance… how do you choose the topics and experiences to write about? Is there something that’s been hardest to confront?

Abdurraqib: I find myself most wanting to write about the moments I’d love to relive. Or the moments that I lived through which didn’t feel real at the time of my living through them. I sometimes think if I shout those moments down an empty hallway, an echo might come back from a voice not my own, and that makes the moment itself more real, more touchable. Someone saying I was there too or I felt this like you felt it. I imagine this feels to me like it is being done out of some sense of a desire to find community. But, in truth, it’s a somewhat selfish pursuit. One that is entirely rooted in an eagerness to not imagine myself alone. The distance between isolation and loneliness is really short, but I cherish the space between the two. I cherish the difference knowing when I want to be alone and knowing that I have not always been alone. And so I imagine that my writing is making a very calculated choice, even as I write it with no one around, with the air of an apartment that only I am breathing in. And so it’s all hard to write about in various ways. It’s all shouting down the hall and waiting to see if something bounces back.

In the acknowledgments section, you write: “To my family and friends and the people who are consistently swelling with patience and grace when I, at times, don’t have any to offer myself.” Can you talk about what you mean by that? As a writer, where do you find motivation or support?

Abdurraqib: I mostly mean that so much of my life now is not the way it was when my closest friends first became my friends, which means that oftentimes, they’re invested in me as a person. Sure, they care about what books I’m writing or what things I’m working towards. But they care more about whether I’m getting enough sleep, or eating food that doesn’t come out of a greasy bag all of the time, or whether or not I’m going to be on time to the party that I said I was coming to. They’re worried about how my anxiety is holding up, and if I need to take a break or not. That’s a real comfort, for me. To have people who not only value my wellness, but demand it — even when I’m not demanding it of myself. As a writer, I look for anything that motivates me to be a whole person outside of the writing I do. And I owe my friends for holding me to that. I owe the people who most want to see me be a whole person outside of the world I’m writing towards.

Does motivation always come from where you expect?

Abdurraqib: Not really, but I also think it has helped me to go into writing with very few expectations for where I’ll find motivation, or if I’ll find it at all. It’s maybe not as glamorous and romantic as I think other answers could be, but I don’t think motivation is a promised thing. I don’t think motivation owes it to us to show up when we desire, or even need it. But I do think that I owe it to the work I’m doing to chase after it, whether or not motivation arrives.

You also thank your friends who aren’t counting how many words you’re writing. What role does word count play in your process?

Abdurraqib: Oh, none at all. I think that I’m often writing until I’ve fulfilled whatever curiosities carried me to the page, or until I feel like I’ve built a sufficient emotional bridge for someone to get across clearly and safely. I don’t often think of word count, but to think “Is this worth it? Is this something that I would start reading and want to see through all the way to the end?” And while I think that’s an honest question to ask during the process, it’s not one that I’m governed by. I suppose I’ve been lucky enough to have good editors, though.

I was so struck by this line: “To Eve L. Ewing, the best sibling in art that anyone could ask for.” What is a ‘sibling in art’? How did having such a sibling help you write this book?

Abdurraqib: Well, in the case of Eve, it’s someone who knows my work, and cares about my work. Beyond that, it’s someone who won’t have you out here looking foolish when it’s time to share your work or ideas with the world. I think Eve has more great qualities than I can fairly list here, but one that I really value is her honesty. I know that I can send something to Eve and have her approach it honestly, and with concern not only for the work, but concern for how the work is coming out of me, and how it will be shared with the world. That our work speaks to each other or is often in concert with each other is an added bonus, and it creates a really rich dialogue between our goals. To know that there is someone close to you fighting to craft the same type of work as you, and writing towards a similar goal as you is vital. Writing can be such an isolating artform. I like to know that I’m not taking it on alone. I imagine that when I’m sitting down to write, I am the whole of every writer who has ever pushed or inspired me or held me accountable or asked more of me when I pretended to have nothing left.

You also dedicate your book to “the memory of Marshawn McCarrel and the memory of Bill Hurley.” Tell us about them.

Abdurraqib: Bill Hurley was a local poet in Columbus, Ohio where I am from. Bill would often pop in at the Writer’s Block Poetry Night, where I’d frequent. I got my start there, reading bad poems on open mics and in slams. In a lot of ways, that room was the first room I felt like a writer in. Bill was one of my favorite writers there, and was always so kind to my work. Bill was older than I was by over 30 years, but wise, funny, and deeply caring. He was diagnosed with cancer, and then beat it, but then it returned and took him in 2016. I’ll always remember how kind he was to my work. How his warmth filled a room.

Marshawn McCarrel was a poet and activist in Columbus. He was a staple at Writing Wrongs, another poetry open mic night I went to often. He was about nine years younger than me, and often one of the youngest poets on the mic, but he was immensely gifted. He had a lyrical dexterity and sharpness that was beyond his years. He also cared about his community, and engaged in activism on many levels, which was a true type of sacrifice. He committed suicide at the start of 2016. There’s a piece about him in the book that I’m really proud of.

“Thank you, reader, for sharing a small corner of this brief and sometimes fantastic life with me” — I love the use of the specific word, “sometimes,” rather than, say, “always.” Why “sometimes”? Which parts of life are fantastic?

Abdurraqib: When it’s warm enough out for the birds to be comfortable in their hunt for a meal, I like to watch the birds outside of my window fight over dumpster scraps before realizing that there’s more than enough to go around. There’s something about how their viciousness turns tender that offers me hope. I like how I walk into my favorite Pita spot in Columbus and the guys behind the counter speak Arabic to me, even though my Arabic is broken and not as good as it once was. I consider this a type of comfort we’re offering each other. I do not particularly care for snow, but I do like the silence that rides in on the back of an especially heavy snow. The way it blankets a city and makes you appreciate being alive and outside when other people refuse to be. I like going to the movies alone and sitting through the credits, looking at all the names of people who worked on the smaller parts of a film, knowing that they might be proud of the fact that someone is sitting somewhere, watching their name crawl along a massive screen and cheering. Yes, assistant costume designer! Yes, person who held a stage light once! Yes, deliverer of boxed lunches, which — I imagine — makes a person a deliverer of joy! It’s all so fantastic. What makes these things fantastic, of course, is that I don’t always have access to them. I can stretch them out in my memory — as I’m doing here — but I can’t always touch them. Where I live, it is sometimes too cold for the birds and it is sometimes too warm for the snow and I sometimes cook a meal from home so that I don’t bury all of my money into the Pita empire and I sometimes can’t go to movies alone if my schedule is causing a particular type of havoc. I imagine if life were always fantastic, those of us living it would have no language to describe or understand it as fantastic. And so, yes, the sometimes gives me something to extend myself towards, always.

Back to the line, “Thank you, reader…,” who do you imagine your readers are?

Abdurraqib:I always hope for people who are like I was: young, eager about music, and looking for someone to talk about it with. I hope those people can find that in my work, the way I found it in critics before me.

Back to the musicians you write about: say, I’ve listened to Fall Out Boy but don’t know their deep cuts. What should I be listening to?

Abdurraqib: Infinity On High is the best album to start with by them, I think. It’s a great meditation on the idea of fame vs. being famous. There’s a difference, I think. And by that point, they were a band coming to terms with fame, but still far out on coming to terms with being famous. It’s kind of refreshing to have this album where the entire thing is kind of like “yeah, we made it. And this kind of sucks.”

DAVID COTRONE is from Plymouth, MA and currently lives in Brooklyn. His writing has appeared in Fifty-Two Stories (Harper Perennial), Catapult, TechCrunch, and elsewhere. He is currently preparing to launch a blog called “Acknowledgments,” an interview series with writers, viewed through the lens of the acknowledgments sections of their books. Who do we acknowledge, and why? You can follow and learn more about this series by following @DavidCotrone on twitter.

DAVID COTRONE is from Plymouth, MA and currently lives in Brooklyn. His writing has appeared in Fifty-Two Stories (Harper Perennial), Catapult, TechCrunch, and elsewhere. He is currently preparing to launch a blog called “Acknowledgments,” an interview series with writers, viewed through the lens of the acknowledgments sections of their books. Who do we acknowledge, and why? You can follow and learn more about this series by following @DavidCotrone on twitter.