By her own admission, Putsata Reang has an “insatiable appetite for research.” As an award-winning author and journalist, Reang is no stranger to reporting and diving into detail. Her debut memoir, Ma and Me is brimming with reported fact. But what happens when facts meet family myths or reporting collides with cultural barriers?

Reang’s approach to writing balances her journalist’s instincts with emotional truths, and challenges nonfiction readers to consider where truth truly lies. In writing her memoir, Reang was faced with challenging questions: “What’s that edge between mythmaking and facts? When a story is told orally and repeatedly, is it taken by the listener as fact or is it taken by a listener as mythology?”

In Ma and Me, Putsata Reang takes the reader from Cambodia, to Corvallis, and back again all the while diving into truths—plural. Reang’s work calls into question emotional truth and factual truth. She asks, “What is our responsibility as writers to be open to both and to adhere to both? To whatever measure we decide?”

Brandon Arvesen: I want to start with a more open-ended process question. When you decided to write this memoir, what was your approach to capturing as much as you’ve captured?

Putsata Reang: I never intended to write this particular memoir. I wanted to do a book on the impacts of PTSD and survivor’s guilt, specifically on my parents. My father was institutionalized two years after we arrived in Oregon after escaping Cambodia. The journalist in me had always been so curious what happened to him when he was in the psych ward. It turns out, I was late by two years. When I went to the psych ward to ask for his records (with his permission), I learned they purged records every 25 years. Had I been curious sooner, I would’ve known what he was treated for. I would’ve known what he was given. He won’t say anything about it, though. I think that in that case, when we’re talking about research, there are true limitations of primary research when it comes to writing our truths. The journalist in me was very frustrated because the journalist in me wants so much information, wants records, wants the interviews, wants everything.

BA: Was it hard to satisfy that part of you?

PR: What I recognize is that coming from a country of war, and coming from a country where the culture around record keeping is different from here in the US (where there’s a lot of rigor around record keeping), it was hard to get those kinds of documents. I had to adjust my own expectations as a memoirist tackling this project to know that there are some facts and some records that I can get, and there’s going to be a lot that I can’t. And that was a hard thing to decide on in terms of content in my memoir.

BA: And how did you make those decisions?

PR: This book went through ten drafts! Those early drafts, it was all fact, fact, fact, fact, fact. There were none of these family myths woven through. And I see the progression of my own thinking during those ten drafts over four years. It was this shift of mentality. Sometimes all I’d have is the myth. And that has to become part of the story, too. There are no documents that prove my great, great, great, great grandparents walked for hundreds of miles into what’s present day Cambodia with a single boiled egg and a ball of rice in their pockets. One small example: I had no quotes in those first drafts. My editor was like, “There’s no dialogue here.” I said, “Well, because I can’t remember verbatim what people said.” And she said, “No, no, no. The point of memoir is not that you’re going to remember at six years old exactly what your parents said. If you have the emotional resonance of what they said, and you can replicate their language and how they speak, you can reconstruct language in that way.”

BA: How did the journalist in you feel about that?

PR: I remember being so adamant. I was like, “Hell, no. I’m not going to reconstruct anything that’s not true. My reputation as a journalist is on the line here, and I’m not going to put out anything that’s not a hundred percent true.” I had to be more flexible and nimble in my thinking. Journalism has always felt to me very black and white in terms of facts and data and research and numbers. Memoir is also true. I think that there’s much more allowance for recognizing that the emotional truth is just as valuable as facts.

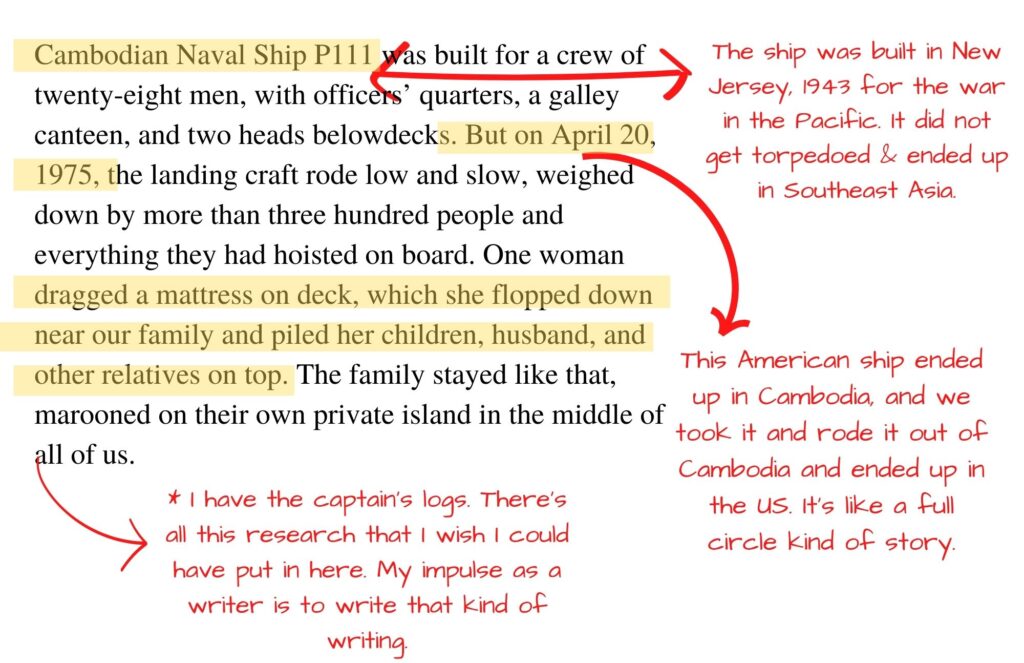

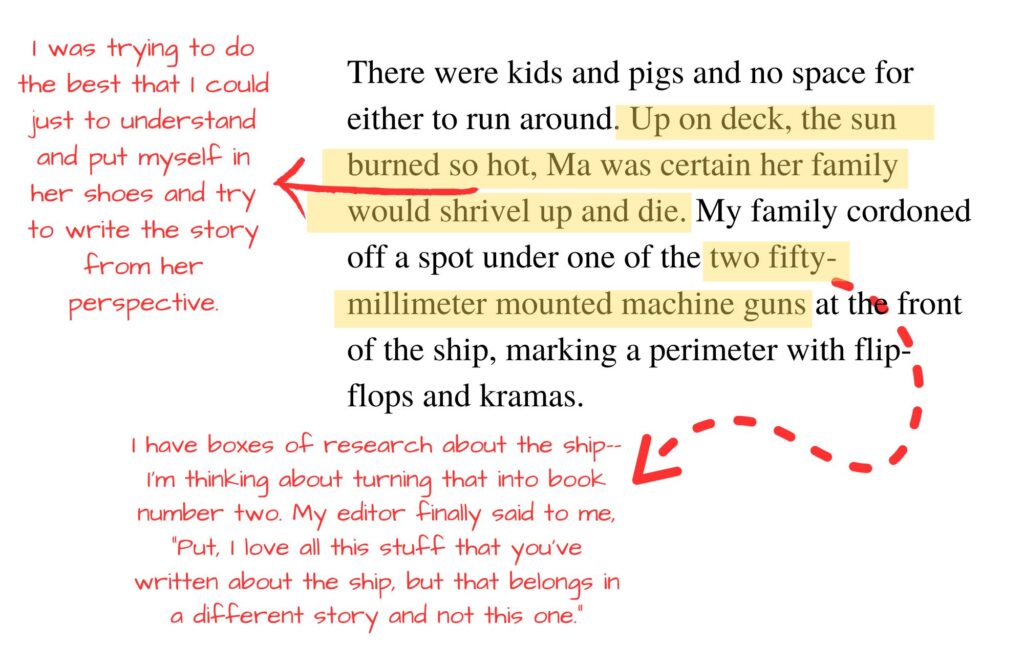

BA: There’s a moment early in the book that stands out to me. You write how your family escapes Cambodia and you fill the pages with details and transcripts, but above all you devote so much to the description of Cambodian Naval Ship P111. You have the crew, the ship’s layout, and details on the landing craft. It’s so meticulous down to the millimeter of the mounted machine guns. Did the journalist in you need to include that level of reporting in the memoir?

PR: I’m so glad you asked. That was a much bigger chapter, and it was definitely more of a journalistic creative nonfiction chapter. The tone didn’t quite fit with the rest of the book, but I was so proud of it. I have boxes of research on the ship. My editor said to me, “Put, I love all this stuff that you’ve written about the ship, but that belongs in a different story and not this one.” And she was trying to hue very closely to the mother-daughter story. She felt my writing going kind of in a different direction with the ship. It was taking the story off a track too far to pull the reader back into the through line of the main story. But I loved writing that chapter. It was paired down from seven or eight pages to two paragraphs.

BA: That’s a lot of revision!

PR: I did a lot of research on the ship because I felt like it was the only way I could picture and understand what my mom must have gone through in that pivotal moment when she refused to throw me in the water. I wanted to plunge myself into that scene with her. The only way I knew how to do it was to just do research on where she was. Her memory is so crystal clear. The way she was describing to me that journey in that moment when the captain told her to throw me in the water, she remembers the colors and smells. Everything in her mind was so clear from that moment, and I was trying to do the best I could to understand and put myself in her shoes. I wanted to write the story from her perspective. And so, the journalist who recognizes the rigor involved in and trying to accurately portray something went down this rabbit hole of research on that ship.

BA: What’s so interesting to me is how you placed meticulous reporting at the beginning of the book next to this description of your mother: “She pedals in fables and folktales, wrapping stories and approximations and gossamer of myth.” Is that then sort of a structural balance? You have her memory, her transcript, and your reporting all built around the myths?

PR: There was no way I could fact-check my mom’s stories other than interviewing other relatives, interviewing other survivors, and kind of triangulating information that way. There just weren’t any records. I feel it is a craft decision to let my mom speak via her own mythology. Ultimately she makes myths out of me. One of the central tensions of the story is my mom being so rooted in Khmer culture, being from Cambodia, and me being the daughter in America, feeling very much American and westernized. And so, in the way in which the two forms of storytelling are set up, it’s also playing into that central tension.

BA: Is there a moment in the book where fact checking your mom or her mythologies uncovered idiosyncrasies or differences central to that craft decision?

PR: Oh, this is an interesting one. I’m so glad you asked. My mom’s age of what we know per her US records is a different age from what I uncovered when I did try to find documents on my parents. I came across an old high school ID of my mom’s. Back then, Cambodian schools, following the French influence, put one’s birthdate on school IDs. And that birthdate was different from what I knew. When I asked my mom about it, the response that I got is similar to the response I get from my relatives in Cambodia right now. The culture of record keeping is so different from the US. There’s zero rigor, there’s zero interest in adhering to any specific kind of record keeping or record keeping in general.

BA: What did you do with that information?

PR: I was really frustrated and shocked because it put me in a dilemma. Which birthday do I use? My mom said, “Put, you’re asking questions that have no answers. You keep pushing me and your dad for actual accurate dates. Nobody in Cambodia has those accurate dates. Your birthdate is just an estimate.” It becomes a dilemma. The journalist in me went with the school ID because I had a physical document in my hand that said this is my mom’s birthday. I went with that even though it was a few years off from how her birthdate is recorded in the US.

BA: How do you square that with the emotional truth and mythologies in the memoir?

PR: There was a second reason why I went with that birthday. When I made a timeline of major events in my mom’s life and I overlaid it on a timeline of mine, I saw greater gears at work. What I realized is that my mother was thirty years old when she carried me on that ship as a baby crossing the Pacific Ocean to come to America. I was thirty years old when I decided to go back to Cambodia to work as a journalist. What are the odds that we would be the exact same age crossing the Pacific Ocean in different ways? I can’t not use her birthdate from a document that was issued from Cambodia, however accurate or inaccurate it is, when it lines up so perfectly with meaning for our story.

BA: You choose the truth that appeases the journalist in you, but it is also the one that creates the better emotional truth. You get to decide. You chose your mom’s birthday, but you chose it not only because of accuracy, but because the emotional accuracy of your lives reflected in that choice.

PR: It’s escalation, right? And that’s craft. Because we’re not just trying to lay out facts in our stories. We have to write in a way that’s going to engage the reader and get them to turn the page. And so of course there’s calculation in that for sure. Somebody might call it manipulation. I would rather call it what it is: craft.

BA: Even though you are a diligent reporter, there’s so much happenstance involved in the assembly of any story. It’s curating that happenstance and framing that happenstance into a narrative that people can engage in.

PR: The story is the story no matter what, but it’s those little micro decisions we make and how we’re going to tell that story. The structure and the scenes that we choose and the themes that we choose, all those little micro decisions add up to become the major craft decision of where we’re going to be taking our stories. And I think that for writers who may be reading this interview it’s an important thing to acknowledge that we, as the writer, have so much agency in how we tell our stories. We have so much power in that decision making and to use that agency to the absolute best ability that we can to make the best story that we can.

BA: And that’s memoir?

PR: You push yourself to the very edge of your own selfhood and see what’s there.