One night a few years ago, I was tidying up my kitchen in Seattle when a text from a New York City zip code lit up my phone’s screen. My friend and co-editor, Kelly McMasters, was at a bar and, accounting for the time difference, it was late. “I just met someone,” she said. I paused with my dish towel in hand, waiting for the next little bubble of information to appear.

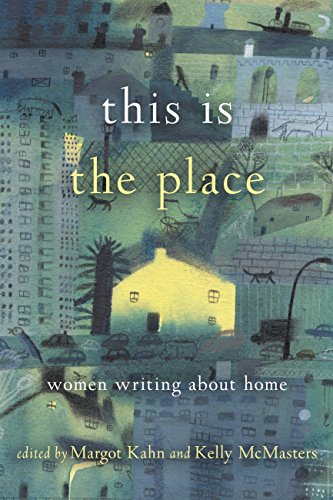

At the time, Kelly and I were putting together a collection of essays titled, This Is the Place: Women Writing About Home, and we were looking everywhere for writers whose work made us stop, sit down, and have to catch our breath. That night, sidled up with the winners of the 2016 Rona Jaffe Awards who had just read excerpts from their works-in-progress, Kelly was sure about one thing: Danielle Geller was a woman we needed to read.

When Danielle offered us an essay titled “Annotating the First Page of the First Navajo-English Dictionary,” we did just that—we read it again and again. We reminded ourselves to breathe. Her work is visceral and intellectual, experimental and elegant. I spoke with the newlywed birder, weaver and video gamer from her home in Toronto, Canada, about family, memoir, indigenous art, and innovation.

MARGOT KAHN: You’re working on a memoir about your familial relationships, most significantly with your mother who died in 2013 when you were 27 years old. How’s this going emotionally for you?

DANIELLE GELLER: It’s really, really difficult emotionally to write this book. And to a certain extent I have to stop myself from starting other projects because they’re a way of procrastinating, a way of keeping me from writing this one. But I need to get this one out of me, out of my heart, before I take on another longer project.

I’ve started thinking about this book or this process as a kind of reconciliation. My mother and I didn’t live close geographically—she lived in Florida and I lived in Pennsylvania for most of my life—so what I knew about her I was told by my dad’s family, and they did not have a good opinion about her. After she died, I inherited her personal belongings, including her letters and diaries, and I started to realize she wasn’t the person or woman who I was told she was. We had a lot more in common than I ever really imagined. So the writing has been a process of reconciling who I thought she was with who she thought she was, and maybe who she actually was. There are a lot of empty spaces that I’m writing into and trying to figure out where I can take liberties and where I absolutely cannot. I’m wrestling with what she would want to be known and what she wouldn’t want to be known.

MK: Did you ever consider calling this a work of fiction, to be free of the conformities of the truth? Or, how do you approach the question of liberty in nonfiction?

DG: One of my sisters really wanted me to write this as fiction. She wasn’t initially comfortable with me being so open or transparent. She’s a much more private person than I am. And although it really is my story—not my sister’s story, and not my mother’s story—a lot of her discomfort was with how people would perceive her and my mother through my lens. But we’ve had a lot of conversations and she has come to understand why it needs to be nonfiction, and why she needs to be a part of this story.

I’m writing the truth as I know it, or as I understand it. A lot of nonfiction writers grapple with the idea of “truth,” but the larger, more interesting question for me is: what knowledge do we value and why? I’ve been puzzling through what people know, what we think we know, and how we come to know it—what our hierarchies of knowledge are. Like, I always trusted my dad more than I trusted the things my mother said. As I got older, there was a shift in the opposite direction. I have to stop and recognize that I will never know what the truth is, but what truth am I picking and why?

MK: Stories with conflicting narratives always seem, to me, challenging to structure. What’s your approach with this book?

DG: I have a really hard time writing a linear narrative. I think that has something to do with the trauma that I’m writing about or how, very often, especially when some stressful or uncomfortable thing is happening, my mind kind of defaults and becomes overwhelmed with all these memories of similar things that have happened. My writing process often becomes a thing that is happening now is a thing that happened two years ago is a thing that happened four years ago… And I think that is sadly a thing that happens in families of addition, that process of recovery and relapse, and you have these moments of here we are again. But when you’re writing a book or a memoir, that backward and forward movement is hard to sustain. It’s hard for a (reader) to feel rooted in place and time. So my editor and I have agreed that organization is going to be the very last thing that we work on.

MK: What’s it like to write this memoir from another country?

DG: When I started writing the book I was living in Boston. I applied to the University of Arizona because it was a fully-funded MFA program and it was in Arizona, and I’d just reconnected with my mother’s family on the reservation and I wanted to be closer to them. While I was there, living in Tucson, I became very close with one of my cousin-sisters and one of my grandmothers, and I love them very much, but the reservation is an incredibly hard place for me to be. There are still members of my family who drink a lot and I was becoming a caregiver to them. I was the person who people would call late at night and I was stopping everything to take care of my family. At the same time, my dad was homeless and living with me. And I was reaching a point where I just couldn’t keep taking care of everyone else and still be a functioning person. I was envisioning the end of my book being my return home—reconnecting with my family and an identity I felt I’d lost—and then I was faced with the reality of no, I’m actually running away. I can’t stay. I think I need this distance to be healthy and whole. But it’s heartbreaking and I have a lot of regret and guilt for leaving again.

MK: What’s your approach to sharing your work with your family members, especially those who appear in leading roles in the narrative?

DG: I do something that I’ve been cautioned against doing. I almost always share what I am writing, pretty early drafts, with the people I am writing about. Not everyone, but the people I’m writing about whose relationships I value most—my dad and my sister, and when my mother was alive, I shared some of my writing with her, too. This is dangerous because I shared my thesis with my sister and we got into a screaming argument and I immediately started asking those questions. Why am I writing about this thing if she doesn’t want me to? Can I write around it, and if so is it the same project? What can I do to protect her? And it stalled my writing process for six months. I couldn’t face my book because I didn’t have any of those answers, and it wasn’t until my sister and I talked again seriously and renegotiated some of those boundaries that I could start writing about her and us and my mother again.

But sharing your work with family is a risk. What if you’re not in a position to come to an agreement with the person? My dad, he read the entire first draft—he’s not painted in the best light, and I don’t think I’m portraying him as a totally bad guy, but he’s done some terrible things. He was like, “this, this, and this were factually not true,” but he was able to recognize that it was my story. He read the entire manuscript, and it was the first book he had read in maybe twenty years. He would brag to people about it on the train. And I think it can be healing to have those conversations before something is published and address those conflicts before it’s consumed by people outside of the family. But there are members of my family who are more distant or who my life isn’t as tied to where I don’t think I can take that same step. Is that cowardice? Is that fear of what will be said? Or is that just trying to preserve my perspective as a writer and the story that I’m trying to tell?

MK: The facts of your Native American heritage and cultural legacy are a driving force in your work. Is your writing influenced by other Native American writers any more or less than by others?

DG: I definitely make an effort to read Native American writers, and there have been so many wild successes this year! Tommy Orange’s There, There and Terese Mailhot’s Heart Berries were huge. Sherwin Bitsui’s Dissolve just released this fall. And I’m already looking forward to Natalie Diaz’s book coming out with Graywolf in 2020! So, I read a lot of Native writers’ brilliant work. It’s so exciting to see their work out and celebrated in the world.

But it’s hard for me to anticipate what will influence my own work. I’m writing a memoir, yes, but it’s nothing like Mailhot’s book; she was doing something raw and emotional in a way that I could never be on the page. People read my work sometimes and say, “But how did you feel about that?” And it’s often hard for me to articulate. I admire Mailhot’s work so much but I find it so hard to write like that myself.

I read a lot of different genres on varied subjects because I never know what’s going to give me an idea or shift the way I’m thinking. For example, “Annotating the First Page of the First Navajo-English Dictionary” was inspired by a sci-fi story. The story was written like an early dictionary of an alien language, and the author was trying to translate how this alien race thought about family and love and relationships. And, around the same time, I had been looking at the Navajo dictionary and thinking about it from the perspective of someone who didn’t speak or read the language, thinking about being able to read the words and definitions but not knowing some of the cultural significance, or where the words came from, or what my connection to the language meant. And so many of the ideas on that very first page resonated with things that were happening in my life at the time. In a class I was taking, Ander Monson gave us an assignment to write about whatever happened on September 22nd, which happened to be the anniversary of my mother’s death. And on that day, I just happened to be on the reservation, working through some difficult things with my aunt and my cousins. So later, I bridged the essay I wrote about September 22nd and the dictionary page that I was looking at, all inspired by that sci-fi story.

MK: What are your literary obsessions?

DG: Old English literature, like Beowulf and the poem about Judith and Holofernes. I love the sound of older Englishes. And I love formally experimental work. I just read Jos Charles’ poetry collection Feeld, which combines both! She is taking the sound of Middle English and writing about being a trans woman and reconfiguring the language to be this familiar but alien beautiful thing on the page, and I was like I can’t believe this is a book that exists in the world. It is brilliant.

MK: Who else are you reading these days?

DG: When I first started writing this memoir, I was reading a lot of memoir. But I’ve transitioned to reading a lot more poetry, especially documentary poetry. Poetry has taught me so much about the line and the image. Some books of poetry that have spoken to me: Anne Carson’s Nox, Solmaz Sharif’s Look, and Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas, which is a book I keep coming back to. And The Book of Jon, by Eleni Sikelianos.

MK: Let’s return to your bio. You write of yourself: She is a member of the Navajo Nation: born to the Tsi’naajinii, born for the white man.Tell me more about that.

DG: This is the Navajo way of introducing yourself. When you meet a person who is Navajo, you say your name but then you immediately share info about who your family is. Tsi’naajinii, the black-streaked wood people—this is my mother’s mother’s blood clan. The system of relationships in this culture is different in that we have a lot more extended family, so even if I meet someone who is Tsi’naajinii but I don’t know the direct blood relationship, we are still considered family. So this way of introducing yourself is a way of establishing kinship with people you meet. I took a weaving class last summer with Barbara Teller Ornelas and Lynda Teller Pete, and after I introduced myself, Lynda gasped, “We’re nalis!” They talked to me like I was their granddaughter the whole class. In my most recent weaving class, I met two women who are my sisters. We sat all together at the start without even knowing. But the feeling of familial belonging is so strong and so real.

The way the introduction translates into English is that you are born to your mother’s clan and you are born for your father’s. The word for white people in Navajo is bilagáana, and that word just means white people. But every time I think about those phrases, the prepositions in particular, I think about my dad. The idea I grew up with, my whole childhood, was that I had to take care of my father. So the statement in my bio is intentionally antagonistic but totally directed at the relationship I have with my father and my connection to white culture.

MK: The whole idea of Native American literature has been debated as, at best, a way to highlight an underrepresented group of writers and, at worst, as an instrument of systemic oppression and cultural fetishism. What’s your take? Do you want your work to be thought of as Native American literature?

DG: The way that publishing and marketing and publicity work, I think it would be impossible for me to write a book and for it to not appear on some Native American literature list, or to not fall into that way of classifying things. Classifications aren’t inherently bad; they are designed to help people parse information more quickly and easily. But classification systems are dangerous because they resist complexity and nuance. There are many Native American experiences I cannot speak to, and it’s important for me to think about how my work participates in this space.

Look at Navajo voices in literature. One of the first books I read by a Navajo poet was Laura Tohe’s No Parole Today, a loud and heartbreaking book about a boarding school experience. Many years later, I read Sherwin Bitsui’s Flood Song, which is visual and breathtaking. Orlando White’s poetry is physical and inventive. Jake Skeets’s poetry is dramatic and traditional, but not in the way I think most readers understand those words. There are names and voices I’m leaving out, but the point I am trying to make is that each of these poets is creating vastly different work, and it would be wrong and unfair to read just one and check off your “Navajo poet” box, let alone a “Native lit” box.

As I build my writing career, I want to create and maintain space for all of our work to be celebrated and read, as other indigenous writers have. I’m thinking of Heid Erdrich’s recent anthology, New Poets of Native Nations, Natalie Diaz’s series of New Poetry by Indigenous Women at LitHub, and Elissa Washuta’s forthcoming anthology Exquisite Vessel: Shapes of Native Nonfiction. Indigenous art isn’t static. Indigenous artists are constantly experimenting and innovating, and there isn’t a singular voice that will define the Native Lit of tomorrow; there are many.

DANIELLE GELLER is a writer of personal essays and memoir. She received her MFA in Creative Writing, Nonfiction at the University of Arizona and is a recipient of the 2016 Rona Jaffe Writers’ Awards. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Brevity, and Arizona Highways Magazine and has been anthologized in This Is the Place (Seal Press, 2017). She is a member of the Navajo Nation: born to the Tsi’naajinii, born for the white man.

DANIELLE GELLER is a writer of personal essays and memoir. She received her MFA in Creative Writing, Nonfiction at the University of Arizona and is a recipient of the 2016 Rona Jaffe Writers’ Awards. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Brevity, and Arizona Highways Magazine and has been anthologized in This Is the Place (Seal Press, 2017). She is a member of the Navajo Nation: born to the Tsi’naajinii, born for the white man.

MARGOT KAHN is the author of the biography Horses That Buck and co-editor of the New York Times Editors’ Choice collection This Is the Place: Women Writing About Home. Her essays and reviews have appeared in The Rumpus, Lenny Letter, Tablet, Los Angeles Review, and Publishers Weekly, among other places. She lives in Seattle.

MARGOT KAHN is the author of the biography Horses That Buck and co-editor of the New York Times Editors’ Choice collection This Is the Place: Women Writing About Home. Her essays and reviews have appeared in The Rumpus, Lenny Letter, Tablet, Los Angeles Review, and Publishers Weekly, among other places. She lives in Seattle.