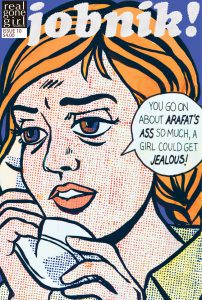

Miriam Libicki is an Ohio-born comics artist who turned her service in the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) into the long-running series jobnik! Published by Libicki’s own Real Gone Girl Studios, jobnik! recounts Libicki’s time as a low-level secretary in the Israeli army, and has been called “the best comic book you’ll ever read about war, love, and paperwork.”

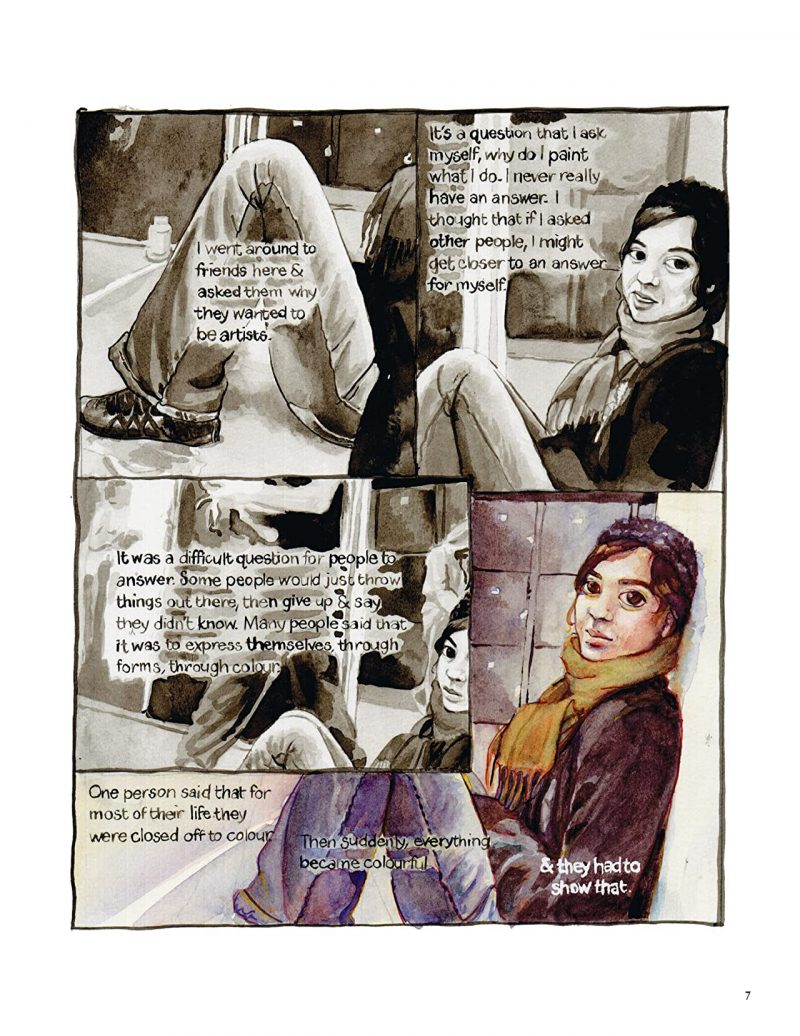

Now living in British Columbia, Libicki published her collection Toward a Hot Jew: Graphic Essays in 2016 with Fantagraphics, the Seattle-based comics publisher known for the work of Robert Crumb, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, the Hernandez brothers, Joe Sacco and many others. Toward a Hot Jew displays Libicki’s wide-ranging interests-from literary theory to immigration politics to art history-while finding new and innovative ways to use the comics page.

Kevin Haworth has spent a lot of time this spring thinking about Libicki’s work. He assigned Toward a Hot Jew for a class on American Jewish Literature, and discussed Libicki’s essays during a panel at the most recent AWP conference. Over Skype from Pittsburgh to Vancouver, he asked Libicki about her approach to creating essays in comics form.

KH: You’re one of the few comics artists that uses the term ‘drawn essay’ or ‘graphic essay’. When I spoke to Jessica Abel, we discussed terminology in comics, and how comics artists don’t necessarily use specific terminology like ‘essay’ in the way that prose writers do. What are your thoughts about that? How did you come to use the term ‘essay’?

KH: You’re one of the few comics artists that uses the term ‘drawn essay’ or ‘graphic essay’. When I spoke to Jessica Abel, we discussed terminology in comics, and how comics artists don’t necessarily use specific terminology like ‘essay’ in the way that prose writers do. What are your thoughts about that? How did you come to use the term ‘essay’?

ML: Cartoonists are often trying to figure out where we fit. There’s a great big history, but it isn’t a linear history. The categories aren’t quite hardened in a way that everybody accepts yet.

There are people who are creating what are clearly graphic novels, but they don’t call their work graphic novels. I’m thinking of Chester Brown calling Louis Riel a ‘comic strip biography.’ Because it was very important for him to be in the lineage of Harold Gray and Little Orphan Annie, he wanted to make clear that was what he was referencing.

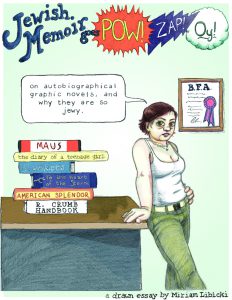

I started using the term ‘drawn essay’ in an art school context. That’s when I did “Toward a Hot Jew,” and that’s the first piece that I called a drawn essay. The respectability of the essay part appealed to me. I do say “I write comics” and I do say “I’m a cartoonist,” but in that particular instance, in order to give people an idea of what tradition I was working in, I called it a drawn essay.

At the time I was reading Donna Barr, who did Stinz. She writes a lot of World War II historical fiction. Some of it is fantasy, and some of it is queer, but it often takes place in the context of European wars. She calls her graphic novels ‘drawn books,’ and I liked that. I like that ‘drawn’ was the important part, especially because hand lettering is really important for me. In my essays everything is hand lettered. It puts the words and the pictures on the same level: they’re both art, and they’re both visual art.

KH: That makes a lot of sense when I look at your work. For you, the lettering is text, but it also performs a lot of work visually. In these essays, you don’t have many traditional panels, or many standard panel-to-panel sequences. So how do you see the text functioning in giving shape to the page?

ML: The text is a voice, and sometimes it’s more than one voice. And then the pictures are a voice also. So then it’s two voices, sometimes more, talking at once.

For example, in my earliest drawn essays I had some serif text, and some sans serif text. The serif text is linear and the voice of authority. The sans serif text is more personal, and has snarky asides. Later I found other ways to show how different text represents different voices. In “Strangers,” about Sudanese asylum seekers [in Israel], I have the quotations from newspapers in sans serif and they’re color-coded as well, so you can see them. And then my personal narrative is drawn in brush and with serifs. In “Stranging the Welcomer,” my editors suggested that I needed something to differentiate what I was saying versus what I was attributing to other people, since I don’t have people’s names after the quotes. At first, my editor said, “I would like you to put those in quotations inside speech balloons.” I thought, I cannot do that. As a cartoonist, that would just make my skin burn-putting a quotation inside a speech balloon. So what we worked out-and I don’t know if people even notice this-is that any speech balloon that is a direct quotation or paraphrased quotation from somebody else is a squared-off speech balloon, whereas mine are rounded.

So, as they say in modernist and postmodernist art history, images are text. And so then the image and the text are both text, and they can each represent multiple authors.

KH: With both of those essays, “Strangers” and “Stranging the Welcomer,” there’s a level of citation and identification of sources that goes even beyond typical creative nonfiction. They almost feel like drawn scholarly essays. I’m not sure I’ve seen anything like it.

ML: The first time I did this was with “Jewish Memoir Goes Pow Zap Oy.” That was the first time I tried to make all my quotes findable, even if I didn’t have one formal way of doing it consistently. That essay was more-or-less commissioned for The Jewish Graphic Novel, edited by Samantha Baskind and Ranen Omer-Sherman. That was my first piece that wasn’t self-published.

KH: How did that commission come about?

KH: How did that commission come about?

ML: I’ve been in contact with Ranen for over ten years. I call him my mentor, even though we’ve never met in person. He got in touch with me after seeing an article in the Forward about jobnik! The only essay I had written at that point was “Toward a Hot Jew.” I sent him that, and he was very enthusiastic about it. He told me that they were putting together a book. I told him my idea [for ” Jewish Memoir Goes Pow Zap Oy “] and he said yes. I sent him parts of the essay as I drew it, and he gave me additional suggestions for what to read, which I liked a lot. After that book came out with my essay in it, university professors started to become more aware of jobnik! Even though it’s self-published, it’s been taught in several courses now, which is super cool. So the opportunities that came out of being in The Jewish Graphic Novel were really unexpected. Ranen even convinced the publisher to have me draw the cover, which I got paid for!

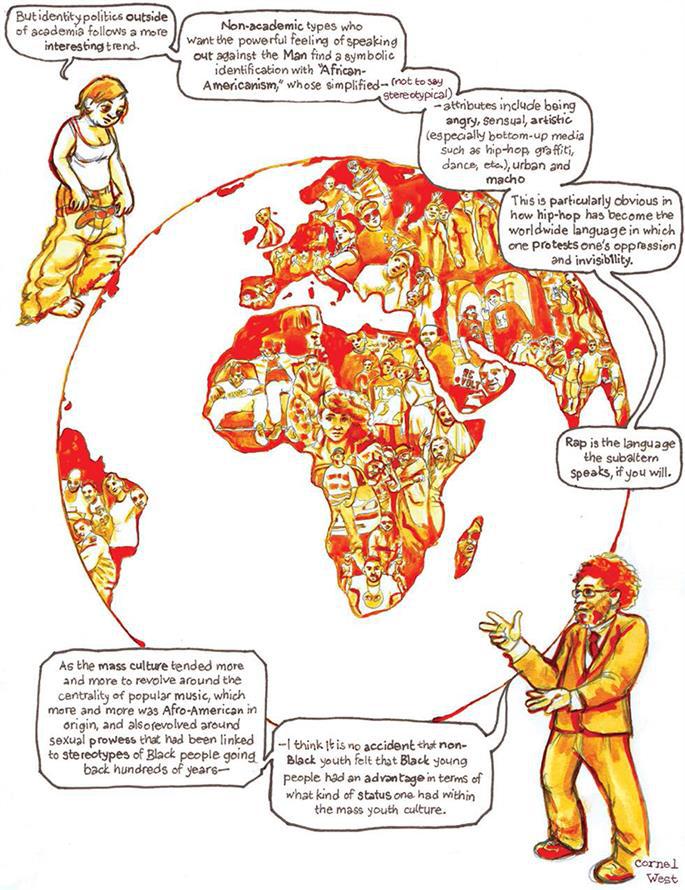

So then I started working on another essay that took a long, long time to write. At first I wanted to do an essay about Ethiopian Israelis, but I didn’t necessarily feel like that was my story to tell. It is a story that I want more people to know about, but not through me. I’m used to the idea of implicating myself and positioning myself in whatever I’m writing about. That comes out of being a memoirist and thinking about post-colonial theory, and from the kind of postmodernism that says: all facts are situated from somewhere.

So I had to figure out what essay I wanted to write. I decided it was going to be about the whole history of Jewishness and blackness. I wanted to write about the whole history of global racism. So I had to figure out what to read. Do you know that there isn’t really one book about the whole history of racism? That would be a really useful book.

Ranen and others gave me some suggestions for what to read. I found out that Jan Fernheimer at the University of Kentucky was teaching jobnik! When I looked her up, I saw that her area of expertise was black Jews. So I approached her and talked to her about my essay, and she gave me a lot of feedback. “Pow Zap” [“Jewish Memoir Goes Pow Zap Oy”] was scholarly, but mostly literary theory. I felt like it was harder to get things wrong in that case. For this essay, which would become “Stranging the Welcomer,” it was essential to find the right sources.

I did basically a year of research. Then I wrote an outline and shared that with people before I started drawing. That led to more guidance and more reading. Once I began to draw, there wasn’t a lot of editing left to do. It was first published in the Journal of Jewish Identities.

KH: That’s an academic journal, published out of Youngstown State. That’s an unusual destination for a drawn essay.

ML: That was my goal. I wanted to replicate what had happened with “Pow Zap”-to make something really personal, in a voice that wasn’t scholarly, in a way that would make sense even you didn’t have a deep background in Jewish Studies. I wanted it to be accessible to a comics fan, but at the same time I wanted it to be scholarly enough for a scholarly publication. I don’t know if I can explain why it was so important to me that it be published in a scholarly publication. But it was important to me. For a while I wasn’t sure if I could get there-if I could to get the essay to that place.

For most of my comics, the destination is that I self-publish them as a zine and sell them at comic cons. But my drawn essays have found some interesting additional destinations. “Strangers” has been excerpted in the Ilanot Review, the English-language literary magazine of Bar-Ilan University. “Toward a Hot Jew” was published on the web site Jewcy. I submitted “Ceasefire” to the New Yorker but I never got any response. Ha!

KH: I want to ask about the publication of Toward a Hot Jew as a collection. How did you wind up working with Fantagraphics?

ML: Fantagraphics has been one of my favorite publishers for a long time. They are in Seattle, so they show at a lot of the same West Coast comic cons that I go to, both indie and literary comic cons. I got to know [Fantagraphics founder] Gary Groth and some of the editors, and I submitted jobnik! to them when I first started it. They sent me a very kind rejection letter. And I submitted jobnik! a couple more times, and each time they wrote me a very kind rejection letter. Eric Reynolds, the associate publisher, and Gary both told me that they liked my drawn essays, and that I should do something with those. So every time I finished a drawn essay I would hand it to them, and they would say, “Thank you.” [Pause.] And so it was always in my mind that they would be one of the publishers that I would submit to when I had enough for a book.

When I was doing “Stranging the Welcomer,” that was in my mind also. I was hoping to place it in an academic context, but I was also hoping to get the overall page count up so I would have enough essays for a book. That’s why I did in an orange ink wash-I wanted to make sure that it could reproduce in black and white for a journal, but my book was going to be in color, because I had a bunch of watercolor essays, so it needed to look good in color also.

I got to the point where “Stranging the Welcomer” was not quite finished, but penciled, so that there was enough for you to see what was happening even if it was ugly. The photo references were just pasted in, there were pencil sketches, and the text was typeset rather than lettered at that point. So I made little binders with all the essays and I submitted them to a bunch of publishers and Fantagraphics said yes.

KH: And you’re still self-publishing jobnik!, right?

KH: And you’re still self-publishing jobnik!, right?

ML: Technically, yes. I haven’t published any issues of jobnik! in four years. But it’s not done. I am going to work on jobnik! again. Any day now.

KH: But now you have a book with Fantagraphics, which is a big name in comics. So does that change how you are thinking about the next project and how you want it to see it published?

ML: Yes, and I am working on the next project. It’s fully scripted and I have twenty pages drawn. So, right now, I’m going to be submitting it to agents and publishers. Not being strictly self-published anymore, I hope I can get favorable terms and/or at least someone interested in what I’m working on.

KH: There’s a line in Toward a Hot Jew where you say to the reader, “I was not always the exaggerated line drawing you see before you.” It’s a very clever moment. I spoke with Jessica Abel about how comics artists use themselves as mediators. It’s different than just seeing the comics artist as a character in a graphic memoir. Instead, you’re speaking directly to the reader, and then commenting on the action in the panel. It’s a special space you-and others, like Scott McCloud-create on the comics page. And your line indicates that there’s a self-awareness about how you are using that space.

ML: Nonfiction prose writers address their readers all the time. But in comics you make that explicit in a different way. If you just put in text, and have it serve as your authorial voice, it winds up being dry and distant. Even more so than in prose. When you have the option of creating a face and body and eyes, it’s weird if you don’t use it.

My biggest influence in that regard was Larry Gonick’s series A Cartoon History of the Universe. Looking back at it, he doesn’t insert himself as much as I remember. He has this conceit where he steps into a time machine, but it’s more bracketed off than I thought. But the way I remembered it, he was standing next to the panels and doing a lot of commenting in a snarky voice.

KH: That series is influential for many comics artists, but it’s not on the radar of most comics scholars.

ML: I feel like I don’t hear people mention Larry Gonick as much as they should.

KH: I wonder if it’s a genre issue. Graphic novels are really well respected now, as are graphic memoirs. But I think people don’t know what to do with a cartoon history of the universe. What is it? It’s a history book, sort of. In the past, comics have gotten away with avoiding labels. But now that they are receiving more notice and more attention from journalists and scholars, books that don’t fit into categories might be more likely to slip through the cracks.

ML: He’s written so many books, and he’s really perfected his style, and I feel like anyone who is looking at a canon, or any academic who’s looking to write about comics much prefers an eccentric genius who writes two books. They’re more interesting to study than someone who takes a workman-like approach.

KH: In terms of how you choose to depict yourself in your work-it has similarities to how other artists use this technique. Your image is fairly abstract, pretty cartoony. So talk a bit about this self-depiction.

ML: Part of it was by chance. I drew “Pow Zap” at the same time that I was re-drawing the early issues of jobnik! to put together the first jobnik! graphic memoir, which was comprised of self-published issues 1-6. And it wasn’t until issue #4 until I got a style where I thought, “Yeah, this is the style that I want to draw the whole series in.” So I finished issue #6, then I went back and re-drew the first three issues.

So I was in the throes of doing that while I was envisioning “Pow Zap” and that’s why she has the particular haircut that she has-because it was the haircut that I had at the beginning of jobnik! And she is dressed in what people in the IDF call chetzi-bet, because that’s how my character in jobnik! ends up a lot. Chetzi-bet is your cotton, on-base uniform. It’s your very casual, doing-work-on-base uniform, and you can take the top off if it’s an after-hours setting. So if it’s after hours, men and women both will be walking around in their uniform pants and their undershirt. And that’s what I wanted for myself as the character. Imagine it’s you and me, and we’ve finished our day of work and had dinner, and now we’re just hanging out in someone’s barracks, sitting on the bed and drinking instant coffee and talking. That’s the environment I wanted to put you in as the reader. It’s not the association every reader would make, but it’s the association that I have with the uniform.

KH: What’s fascinating about that is the work that the image does to create a certain voice, and a certain environment for how that voice reaches the reader. It’s how you create the context for the kind of discussion you want to have. It’s informal. But from my own experience in Israel, casual settings can lead to super-intense discussions. You’re at a café, or in someone’s living room, and you’re just hanging out, and then all of sudden things get super heavy.

ML: Totally. That’s Israel.

Other people handle this technique differently. Scott McCloud [in Understanding Comics] is like, “I’m a teacher in the front of the classroom, and I have my blazer.” Marv Wolfman’s history of Israel [Homeland] is kind of similar. He has a narrator character who is fictional-she’s supposed to be a hot Israeli professor, I guess-and so she’s like “I’m the teacher, and I’m going to teach you things.”

In my case, it’s not like I’m the teacher or the authority. And yet, I want to hold forth and talk at you for hours and hours. But just as a friend!

KH: Prose writers spend so much time trying to create and nurture an essayistic voice. But you get to draw a picture, and pow, there you have it.

ML: That’s something I like about being a cartoonist. I don’t have to think too hard about description.

KH: It seems as if you did think about it, though, and then created it very efficiently. It’s a very efficient storytelling device.

ML: So people have asked, “Why is she dressed so provocatively?” I think it’s weird-that people think that image is so provocative. But it’s also telling that people ask that. I did it because it felt natural, but also because in the jobnik! story, it’s very natural for the character’s body to be front and center. A lot of what’s happening is late adolescent stuff, and body image stuff, and gaining weight and losing weight and hooking up.

So I didn’t put a lot of thought into it in the beginning, but when people reacted that way, I was glad that’s how I did it. I’m glad that she has her cleavage out. I’m glad that she doesn’t look too dignified or too neutral. All knowledge is embodied, and this body is not a neutral body. This body is a very female and non-athletic and slouchy body.

KH: I’m very interested in this. You can’t do this in prose, and you can’t do this in painting. But you can do it in comics and comics-like spaces, where you’re looking at the person who’s talking to you.

ML: But, as I point out in “Pow Zap,” if I’m actually in front of you and talking to you, then I can’t control how you see me. With a drawing, I can control it a little bit more. People will have different associations, but I can mediate this experience. I can be the one to tell you, “This is what you see when you see me.”

MIRIAM LIBICKI is a graphic novelist and artist living in Canada. She has been cartooning since 2003, and screenprinting since 2005. Her primary themes are culture clash and the construction of identity, usually through the prism of her Jewishness and dual American-Israeli citizenship. She is the creator of the autobiographical comic series, jobnik!, which has run from 2005 to the present, and recounts her service in the Israeli army during the second Intifada. Her most recent book is Toward a Hot Jew, published by Fantagraphics. Her other nonfiction comics have been published by Rutgers University Press, Alternate History Comics, the Ilanot Review, and Cleaver Magazine. (@realgonegirl)

MIRIAM LIBICKI is a graphic novelist and artist living in Canada. She has been cartooning since 2003, and screenprinting since 2005. Her primary themes are culture clash and the construction of identity, usually through the prism of her Jewishness and dual American-Israeli citizenship. She is the creator of the autobiographical comic series, jobnik!, which has run from 2005 to the present, and recounts her service in the Israeli army during the second Intifada. Her most recent book is Toward a Hot Jew, published by Fantagraphics. Her other nonfiction comics have been published by Rutgers University Press, Alternate History Comics, the Ilanot Review, and Cleaver Magazine. (@realgonegirl)

KEVIN HAWORTH is a novelist, essayist, and literary translator who writes about Israeli literature, arts, and culture. He was a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize and was awarded the Samuel Goldberg Prize for Emerging Jewish Writers, the Columbia Journal Nonfiction Prize, and a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Creative Writing. Formerly the Executive Editor of Ohio University Press & Swallow Press, Haworth has taught creative writing and literature at Arizona State University, Ohio University, and Tel Aviv University. The author of a novel, two collections of essays, and an anthology on writing, Haworth’s forthcoming book, Rutu Modan: War, Love and Secrets, is a book-length study of Israel’s most prominent comics artist.

KEVIN HAWORTH is a novelist, essayist, and literary translator who writes about Israeli literature, arts, and culture. He was a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize and was awarded the Samuel Goldberg Prize for Emerging Jewish Writers, the Columbia Journal Nonfiction Prize, and a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Creative Writing. Formerly the Executive Editor of Ohio University Press & Swallow Press, Haworth has taught creative writing and literature at Arizona State University, Ohio University, and Tel Aviv University. The author of a novel, two collections of essays, and an anthology on writing, Haworth’s forthcoming book, Rutu Modan: War, Love and Secrets, is a book-length study of Israel’s most prominent comics artist.