In 2012, my first book came out – a memoir called The Stone Thrower. It centered around my father’s life—an African American quarterback who was overlooked by the NFL in 1972 despite an undefeated record in college, because black quarterbacks weren’t common in civil-rights-torn America. A national sports network made a documentary based on the book. But even with the documentary and with positive reviews from high profile writers like Lawrence Hill, the book arrived quietly. There were no invitations to festivals, no major awards.

I was disappointed but not discouraged. I had become a writer.

At the literary events I attended, there were very few people of color, even at events in Toronto – a large, diverse metropolis. When people of color were on panels, they spoke of “home” or immigration or “writing the other.” They were rarely workshop leaders. When the We Need Diverse Books organization campaigned in response to similar concerns at BookCon 2014 in New York City, I decided to do something about the imbalance. I decided to create a festival that would start with diverse writers – where marginalized authors weren’t an afterthought or tokens, but the central focus of the lineup.

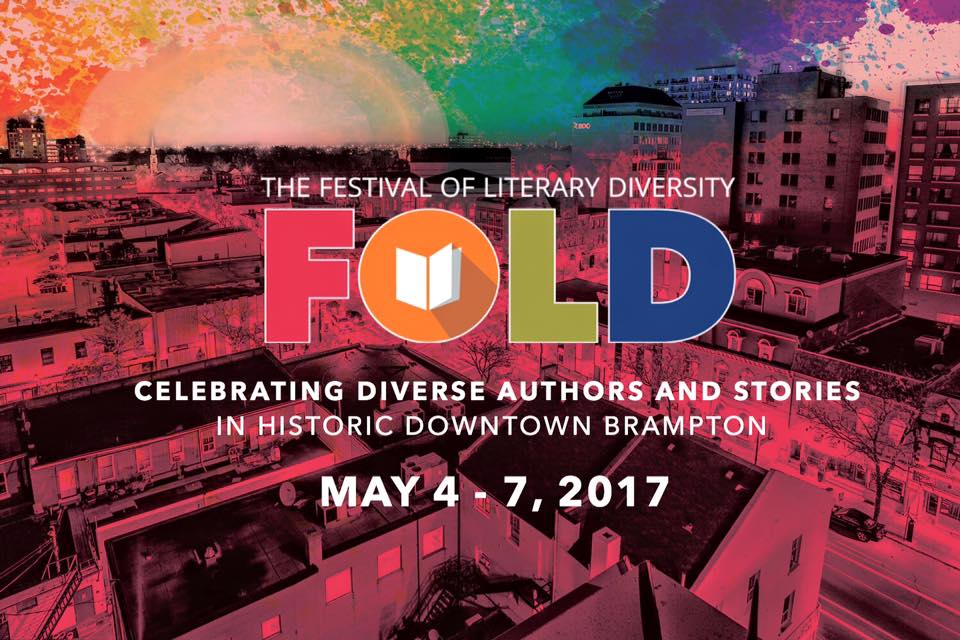

The Festival of Literary Diversity (FOLD) would focus on authors from underrepresented communities – people with lived experience across the spectrum of age, ability, culture, creed, gender, race, and sexual orientation. We were also interested in stories that were written in different genres, particularly by people of color who are often further marginalized within their genre. We wanted to challenge the very narrow confines of “good” or “mainstream” writing.

We thought we would have trouble finding enough diverse authors. But what we found was an abundance of yet-unknown or moderately known storytellers – many highly skilled, profound storytellers. We knew early on that this work was going to be hard – the choosing and organizing.

Our planning team spent long hours debating important, occasionally awkward, conversations. How does it work if their diversity is invisible, for example? Do we aim for a particular quota from communities and groups? If we have a panel on faith, for example, do we need to cover all religions?

On May 6, 2016, the Festival of Literary Diversity launched – the first festival in North America to focus specifically on diverse authors and storytellers. We raised more than $150,000 and had over 40 authors delivering more than 30 sessions. That weekend, more than 600 people came to Brampton, Ontario–a suburb of Toronto that’s often underserved and ghettoized on account of its proximity to Toronto and its highly diverse makeup, respectively. But the event exceeded all of our expectations and taught us so much.

We learned that providing a space and an event that adequately serves those who have been historically marginalized is always harder work. It takes more effort, more digging, more money. These are the reasons so many people don’t bother. They start with what they know, what they can afford and what they can get away with, and they stop there.

And while inclusive programming always takes more work, we also learned that those efforts always reaps better results. When you put marginalized writers in positions to speak as experts in craft—a position rarely provided at many festivals, where they tend to concentrate their talks on diversity—you elevate their sense of worth and value in their own eyes and in the eyes of the audience members. You attract a more diverse audience and create more meaningful conversations. You counter systemic oversights, which feed the careers of certain writers at the expense of others.

Arts curators and programmers have an incredible responsibility. They play a critical role in determining who gets read and who gets known. They make and shape careers, and they need to do so carefully and thoughtfully.

Editors and programmers need to ask themselves important questions:

What stories are you more inclined to like, choose, or support? What stories make you uncomfortable?

They need to reflect on how these answers might contribute to professional blind spots—when personal experience limits their ability to fairly assess the merit of a particular genre, author, or work.

Strive to pay your writers and start with your most underserved voices at the planning and submission stage. I could speak for hours on this subject and have (see my four-part webinar series with Ontario Presents). And continue to evaluate how well you’ve done and what you could do better.

Last year, we initially didn’t have any disabled writers in the lineup. There were reasons—some good, some not as good—but when given the opportunity to correct it, we did. This year, we started out by searching for a richer range of disabled voices. In 2017, three of our authors identify as disabled. That’s not to show off. That’s to demonstrate that even at a diverse festival, there are voices we will continue to overlook if we don’t intentionally set out to represent them. So be intentional.

Let me say that again: Be intentional as a reader, as an editor, as a literary programmer.

JAEL RICHARDSON is the author of The Stone Thrower: A Daughter’s Lesson. The book received a CBC Bookie Award and earned Richardson an Acclaim Award and a My People Award as an Emerging Artist. Her essay “Conception” is part of Room’s first Women of Colour edition, and excerpts from her first play, my upside down black face, are published in the anthology T-Dot Griots: An Anthology of Toronto’s Black Storytellers. Richardson has an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Guelph, and she lives in Brampton, Ontario where she serves as the Artistic Director for the Festival of Literary Diversity. (@JaelRichardson) * Editor’s Note: Jael moderated an outstanding #AWP17 panel titled “Creating Space for Marginalized Writers: How to Create a Diverse Programming Lineup,” with Léonicka Valcius, Kathleen Frase, Nailah King, and Bänoo Zan.

JAEL RICHARDSON is the author of The Stone Thrower: A Daughter’s Lesson. The book received a CBC Bookie Award and earned Richardson an Acclaim Award and a My People Award as an Emerging Artist. Her essay “Conception” is part of Room’s first Women of Colour edition, and excerpts from her first play, my upside down black face, are published in the anthology T-Dot Griots: An Anthology of Toronto’s Black Storytellers. Richardson has an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Guelph, and she lives in Brampton, Ontario where she serves as the Artistic Director for the Festival of Literary Diversity. (@JaelRichardson) * Editor’s Note: Jael moderated an outstanding #AWP17 panel titled “Creating Space for Marginalized Writers: How to Create a Diverse Programming Lineup,” with Léonicka Valcius, Kathleen Frase, Nailah King, and Bänoo Zan.

This is the fourth installment in a series on race, gender, intersectionality, and literary responsibility. The first three include: “An Editorial Roundtable,” Melissa Chadburn‘s “Economic Violence”, and Purvi Shah‘s “To be True in Deed to Anti-Racism Values.” Additional brief essays and interviews will be posted over the coming week. We encourage you to share this series and join the conversation in the comments section of each post. All published posts within the series can be found here.