I came to nonfiction late in my writing life.

It was always something others were doing, something I wasn’t able to do myself. Writing an essay was a skill you either had, or didn’t, and there was no developing it. When you read the work of Eula Biss or Roxane Gay or Matthew Gavin Frank, three of my favorite nonfiction writers working today, you see it not as a sum of its parts—the travels, the research, the interviews, the deep-dive into the topic—but as this thing that has just been sung into existence from their minds and onto the page.

I realize now how inane this is. I recognize, I do, that like all writing, you work on your craft, you seek guidance, you grow with every piece you write. This is what drew me to the micro-essay as a form of experimentation, specifically micro-essays written on Twitter.

See, I am a Twitter apologist. I recognize its many flaws—for example, how it handles trolls and hate speech—but I think it remains, undeniably, a writer’s greatest tool. From promoting your work, connecting with the writing community, talking to editors, finding out about awards and contests, I can’t imagine what people do without it.

Eventually, I turned to the idea of Twitter as a writing medium. I wanted to recount some memories, some specific retentions that informed my writing life or my personal life in some grand way. I wanted to engage with my Twitter friends. So last year, I wrote my first Twitter essay about my love of landscapes and my distant relative Lincoln Ellsworth—how learning about his exploits as a polar explorer continues to fuel my obsession with place in my work.

It happens organically: something in the real world triggers a memory, gets me thinking about what it meant—both then and now—and I’ll be off.

Sometimes I write a Twitter essay on my phone, but, see, I have big, unruly thumbs. I misspell, I mess up. So I do one of two things:

- I sit down in front of a blank screen with an idea that’s been churning in my head and write stream-of-consciousness blocks of text, keeping in mind (roughly) how many tweets is appropriate. But I never let myself get in the way of working out the original thought. I let each idea build on the last, and only once I get it all out will I edit slightly, separate it into Twitter-sized chunks, and put it out in the world.

- Or I’m already on Twitter, and I just need to talk. I’ll be tweeting about something, responding to someone, and then it hits me, some idea or memory, and I go for it. I have to be vigilant, ignoring what people are saying, what’s resonating with my followers, and get it all out before I lose momentum and it’s gone completely. I write and write until there is no more, emptying myself of this earworm.

In both cases, it’s the opposite of my approach to fiction, where there’s a lot of initial plotting and tinkering before my stories ever hit the page. Here, I tinker as I write, don’t let myself edit until it’s all over, and trust that it is going to come out as a story—a good story. This spontaneity is key.

It’s not easy. I normally obsess over every tweet. I don’t censor myself, but I worry about offending, how something might be taken. My Midwestern brain and heart worry. So the Twitter essay is, really, an exercise in trusting myself—knowing who I am and saying things on the fly. It’s exhilarating and frightening in the same bound, but it is teaching me to learn to let go. It is teaching me a certain kind of creative freedom.

I’ve written of the time I moved out to Hollywood and met a girl who sells her possessions to a WE BUY GOLD place or how working with puppets at my church during my formative middle school years made me start reaching for things in life that made me truly happy. The Twitter micro-essay has allowed me to ramble on, to open up, connecting memory to meaning in a way I never have before.

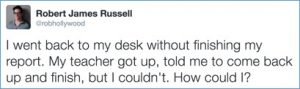

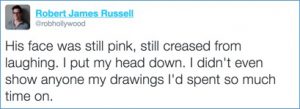

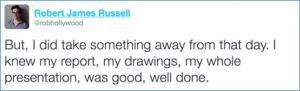

Take, for example, the last Twitter essay I wrote, about a third grade report on Tasmanian devils, and how my teacher and classmates laughed at my mention of how they received tattoos to mark and track them. As I rationalized on Twitter:

Recounting this experience on Twitter helped me process this memory and how I’ve grown from it. Twitter’s 140-character limit forced me to consider every word as I typed and discern what was necessary to the narrative. I believe, I do, that if I had started this short essay on the page—not on Twitter—it either would not have come out at all or been a long, jumbled mess without any sort of structure or get.

I like the definition of essay used in visual arts best: an initial sketch that serves as the basis for the final piece. It tests the work’s composition, it helps you visualize the outcomes—it is an attempt. This is, for me, what the Twitter micro-essay is: an attempt, a way to experiment in the nonfiction genre.

Once I write a Twitter essay, I tend to then go back, shore it up, post it on my website in a more complete form. Perhaps I’ll eventually stop—when I feel more confident in my ability to write nonfiction, when I no longer feel I need immediate feedback. But part of me will always appreciate this method of exploring the minefield of memories in my brain, to make some sense of where I’ve been and where I have yet to go.

ROBERT JAMES RUSSELL is the author of New Plains (forthcoming, 2017), Mesilla (Dock Street Press) and Don’t Ask Me to Spell It Out (Whiskey Paper Press). He is the founding editor of the literary journals Midwestern Gothic and CHEAP POP. His work has appeared in a wide range of journals, both print and online. In 2016, he was awarded Runner-up for the Passages North Waasnode Fiction Prize. You can find him online at robertjamesrussell.com. (@robhollywood)

ROBERT JAMES RUSSELL is the author of New Plains (forthcoming, 2017), Mesilla (Dock Street Press) and Don’t Ask Me to Spell It Out (Whiskey Paper Press). He is the founding editor of the literary journals Midwestern Gothic and CHEAP POP. His work has appeared in a wide range of journals, both print and online. In 2016, he was awarded Runner-up for the Passages North Waasnode Fiction Prize. You can find him online at robertjamesrussell.com. (@robhollywood)