Jeannie Vanasco is no stranger to writing her way through the hardest of material. Her debut memoir, The Glass Eye (Tin House, 2017), was a testament to the larger-than-life heroic figure of her deceased father alongside the complications grief (both his and hers) infused into their lives. In her second memoir, Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was A Girl (Tin House, 2019), Vanasco revisits her own sexual assault by interrogating the past and interviewing the man who assaulted her years before. But in her forthcoming third memoir, A Silent Treatment, Vanasco struggles to both honor her mother and be honest about her. The memoir asks what writers owe their parents and challenges the idea that memoir is strictly about the past. Vanasco writes, “We tell stories about the past to make sense of why we feel or think the way we do. But we don’t really know anything.” The result? A beautiful exploration of mothers and daughters, silence, and what it means to write in the moment.

Jeannie Vanasco sat down with True’s managing editor, Brandon Arvesen, for an annotated interview about how to craft in the middle of the moment. A Silent Treatment is available September 9th from Tin House.

Brandon Arvesen: In A Silent Treatment, you put the story in conflict with questioning whether you can write the story. You’re looking for an answer to a question, but also asking if you can write your way to that answer of that question. It creates a tapestry structure that feels chaotic yet organized. What was your approach for stitching all this together?

Jeannie Vanasco: I like writing from within an experience. Conventional wisdom is, “Wait until you’ve had distance to write about it.” I don’t believe we ever have perspective. I believe the moment that we’re experiencing is the truest thing. And so to write from within the experience is really interesting. But then you have to give shape to it. I think those questions of, “How am I going to write this?” have something to do with both wanting to be as honest as possible, confronting what’s currently on my mind, and helping me get at some of the ethical questions about writing memoir. That meta-layering is helpful, but also when you’re writing from within an experience, it is harder to see the structure. I am trying to give the effect of it, but it certainly wasn’t written that way. During the revision stage I start thinking, “How do I give shape to this in an authentic way?” And a lot of times that’s a means of figuring out particular conflict points and varying the types of conflict. So I’m thinking through all of these craft issues as I’m experiencing it. It could also be because I teach students about creative writing. Craft is often on my mind.

BA: This is a book about your mom not talking to you. Yet, you have her voice interjecting constantly. The reader “hears” from her in parentheticals. Once you had your conflict points, how did you decide where to place your mom’s voice in a book about the absence of her voice?

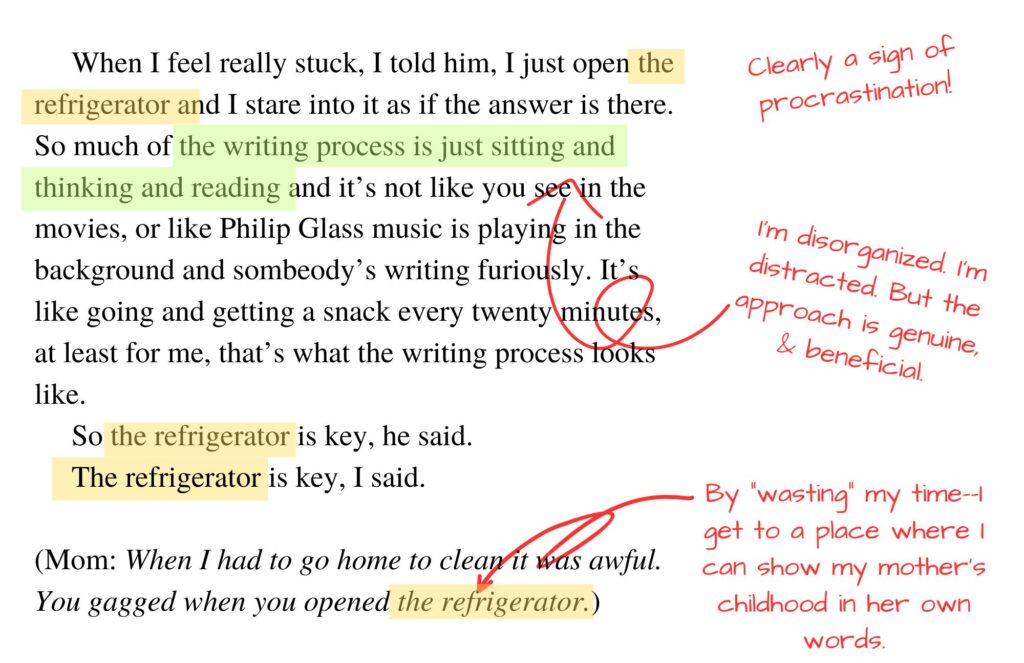

JV: The most honest answer is probably moments when I got bored with the manuscript. I’m writing about a finite period of time. Writing everything in sequence: this happened, and then this happened, and this happened, this happened… that can get boring very quickly. Instead, I’ve got scraps and ideas all over the place in different notebooks and I’m thinking, “Okay, where does my mom as a character need more context?” I would think about which ones would help me pivot to a surprising place. So I write a scene where I open my refrigerator and look into it hoping there’s an answer. In the narrative, I’m procrastinating. But instead of writing what comes next, I think about what my mom would say about her refrigerator when she was a kid. And then that helps me get to something about her mother. If any of that sounds at all organized, it wasn’t. I don’t know how to write a book. I know I’ve done three of them, but I just feel like each is different and I wait for my editor to tell me to step away.

BA: That’s a great quote. Jeannie Vanasco: “I don’t know how to write a book.”

JV: Yes! And I stand by it.

BA: You use the word “boredom,” that is a helpful concept to think about. You have this collection of things your mom said, and you use them to craft new context each time they come through. If you’re bored, go back to the material. What do you have to disrupt the flow?

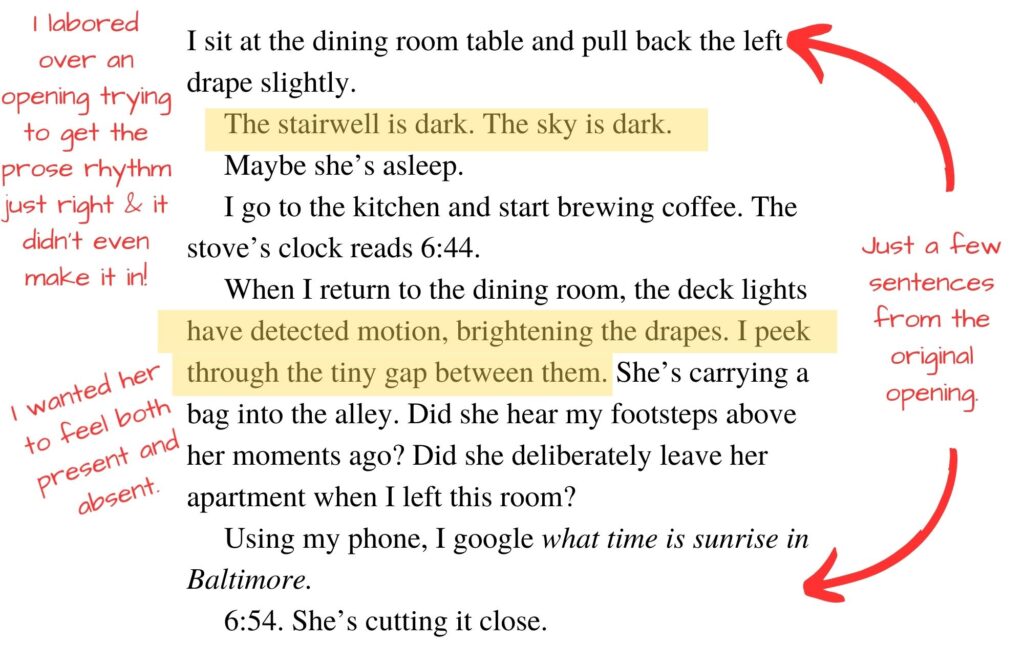

JV: The moment I think I need to write toward a particular moment, I try to back up because I don’t like to do that. I think a lot of times the answers are in our own manuscript. That sounds kind of cheesy. “The answer has been there all along,” but once I know what the opening of a book is, then I can identify and even make a checklist. This sounds very methodical and I’m not usually this way, but I’ll ask myself, “What are the themes?” “What are the objects?” “What objects can I come back to for a sense of coherence?” This is embarrassing, but there was a passage I thought was going to be the opening of the book. And I worked on it for hours every day for weeks. My partner, Chris, would come into my office and ask, “Are you still revising that?” I thought that after I figured it out, everything else would click into place. And this would go on and on and it wasn’t helpful, but I couldn’t break out of it. So it’s easier said than done, but I think once you have the beginning of your project, once you know what that is, any craft issues you’re facing later on can likely be answered by that opening.

BA: What was it about that passage that you thought you needed and how did you wind up with the current opening? What were you looking for and what did you find by not using it?

JV: That passage didn’t even make its way into the book completely. I wanted this moment where my mom was walking past the window. She’s so close to the house; she looked ghostly. I’m just seeing her silhouette go by, and I labored over that scene. You could tell I labored over it. I wanted to show something about how I perceived her and how she was there but not there. I thought this moment was the opening, but that’s not the tone I wanted to set. I wanted a very low to the ground modest tone of, “I forget words.” That felt right.

BA: You question the nature of memoir writing. “As a memoirist, I prefer to inhabit the present because I mistrust my memories.” As you’re writing from within the experience and questioning the validity of what you remember, do you have a process for vetting your memories or fact checking them?

JV: In some instances, I’m okay with sticking to what I remember. I use the book’s meta-aspect to acknowledge that I could be wrong. Other times though, I looked through old photos or objects. I’ve saved a lot of stuff from childhood. It’s interesting when I see a photo and suddenly something I haven’t thought about in a very long time feels very rich. What I’ve landed on is that I could be wrong, but it’s interesting that these are the things I remember. What does it say about me now and the state I’m in now that I’m remembering it in this way? So, for example, my mom tells this story about dropping me off for kindergarten. She says I immediately got out of the car, and I was like, “Bye.” She’ll tell this story and she thinks it’s funny. All these other kids were crying for their moms, and I was waving goodbye and hurrying in. My mom will say, “You were very independent” and she admires that. But I think she includes that detail of the other kids crying because sure, on some level that had to have hurt. And so, I think the details that we choose to include say something about where we are now. Any detail we choose to include, we are including it for a particular reason. We could cast an old memory in a different light of funny or sad or whatever. How do I fact check memories? Sometimes it’s a matter of checking them against somebody else’s memories. I want to include that conversation and let the other person correct me and include them correcting me in the manuscript.

BA: So, you’re not writing from a place of doubt, even though you mistrust memories at times. You’re exploring what that doubt or lack of doubt says about who you are presently in the book?

JV: Ultimately, yes. But if I think about craft too much while I’m doing the writing, I’m not going to move forward. If I’m thinking about the effect of certain techniques, that’s when I get stuck. So letting myself write a very messy draft is very helpful to me.

BA: How did having her permission while cohabitating inform the process? You’re writing about her while she’s alive and with you. I’m also writing about a parent that’s alive. So many memoirists struggle with deciding whether to write about a person in the now or wait until that person is gone to write about them.

JV: I don’t believe in waiting until someone dies. When I was in conversation with Michelle Orange about her memoir about her mom, an audience member said, “Well, I’m going to wait until my mom dies to write about her.” And my mom was in the audience. I was looking at her like, “No, I’m not doing that.” It was helpful to know I had her permission, and I think it’s helpful that I’ve published two memoirs and that she’s read those. A lot of what’s inside of those two books came as a surprise to her. I tested the waters with a New York Times essay that addressed her silent treatment. I thought, “If she’s okay with this, then maybe I’ll be okay with the book.” I ran by her what was in the book. But it was very important to her to not read it. My mom can acknowledge it was emotionally immature what she did. I can be very emotionally immature, too. We all can. But despite that, she’s very emotionally mature about memoir and what I’m doing, and that’s admirable. I’m very lucky. I think a lot of people don’t have that with their parents. But just because someone consents to you writing about them doesn’t mean it’s not uncomfortable. I had her consent, but I questioned it. Does she think she has to give me her consent? I could get stuck in a loop questioning motivations. Having the permission made it easier, but it didn’t make it easy.

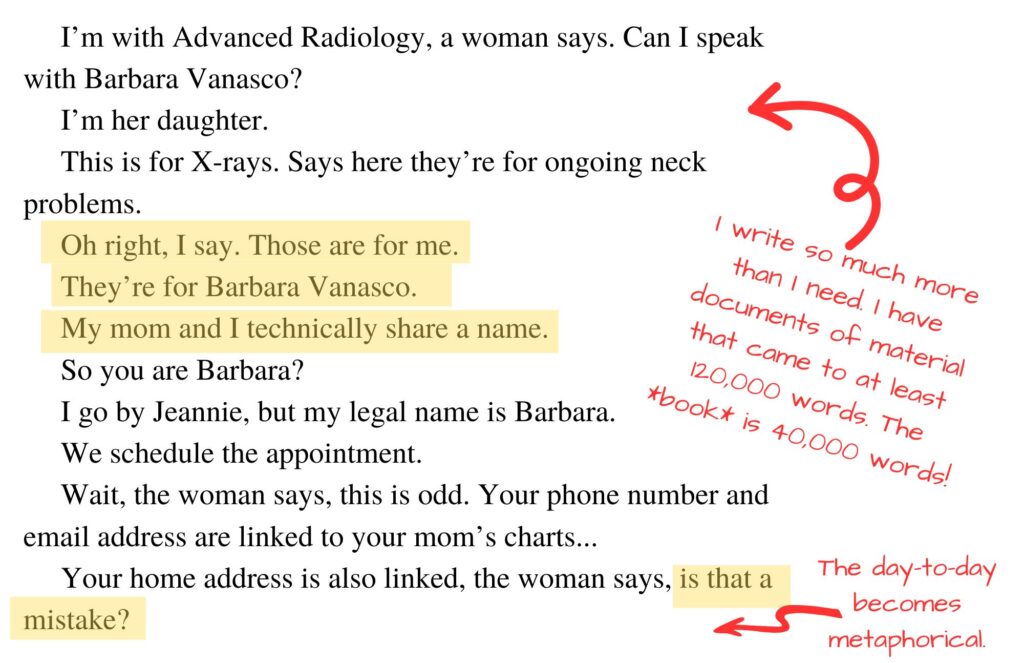

BA: You have scenes writing from inside the experience that probably wouldn’t have been in the book had you waited. You have these little moments that wouldn’t seem significant in a future where your mom had passed away. Like the call from her radiologist…

BA: How do you know what to keep? What to pay attention to?

JV: There are a lot of scenes I wrote that I worked really hard on but didn’t make sense in the book. I did a ton of research that didn’t make its way into the book. I think it’s a matter of knowing that I don’t know, and to write it and figure it out later after I have a sense of what the narrative arc is. I only realized later after doing the whole manuscript, that there was no conflict between Chris and me. I need some of that. And one of the big conflicts we had was he thought I should just go end the silent treatment. And I hadn’t included that. And I was like, “Oh my God. Of course I need some scenes of him asking, ‘Why don’t you just go down there? Why don’t we just interrupt her? When should we see her?'” That conflict shows the reader my mom is avoiding me, but I’m also avoiding her. But I don’t know when I’m writing the book what necessarily should be there. Sometimes I’ll have a full draft, but realize there’s still something missing. A lot of times stuff comes out in the last month of working on it.

BA: Do you remember anything specifically that you added in the final stretch?

JV: When I write about the time we had COVID, that wasn’t in here for the longest time. I’d lost that. And then I realized how funny it was that my mom used the silent treatment after Chris and I quarantined. Does she feel left out or something? That came in much later.

BA: And it allows the reader to see how confusing these silent treatments are to you. And by extension they immediately confuse the reader which creates a nice narrative propulsion.

JV: I needed to show her being in some of the silences. But as soon as I sense an easy cause and effect, that makes me uncomfortable. Hindsight makes past experiences look so much more organized than they actually were. But I needed that COVID passage because it was another example of Chris and me being utterly confused about what went wrong. There’s no possible way my mom can blame me for having COVID. Something else is going on and I don’t know why. And it’s also another means of showing that something’s going on with her. It’s not about me. And I don’t yet see that as a character.

BA: Halfway through the writing you find letters your mom wrote. How did those “wrench letters” affect the writing?

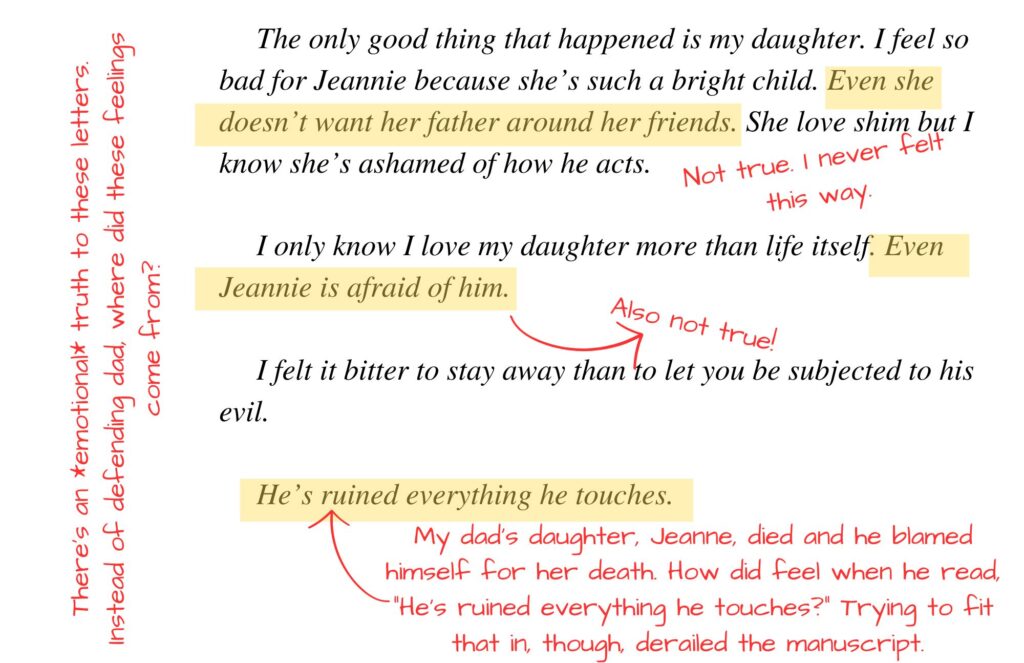

JV: When I found the letters, I was devastated because in them, she’s saying that I was ashamed of my dad, that I was afraid of him, which was not true. And she was trying to hurt him by putting these things in the letters. So I was devastated. If I had waited to write this book, though, it’d be hard to recover just how bad and how crushing that felt. People ask if this was cathartic. Every time I publish a memoir, I get asked that question, “Was it cathartic?” And it doesn’t bother me necessarily, but I’m not writing for catharsis even when it does come. Sometimes it comes from that intellectualizing we’re told not to do. Therapists will say, “Stop intellectualizing.” But on some level, I think it’s helpful. I could distance myself enough so that I wasn’t just completely unable to function. I find the letters and I think, “Oh, well, this explains something. This helps me understand.” Finding the letters revealed the silent treatment isn’t unique to me. It is something she’s done to other people she loves. The letters got me to question things.

BA: How did you approach incorporating these letters when what they claim is inaccurate to your memory of childhood?

JV: The letters helped me access some anger. I was mad at my mom for writing what she wrote. But I knew, for example, my dad didn’t keep her away from family. My dad really believed in family. It was my mom. So often in my childhood we’d have impromptu games of hide and seek. I didn’t know her family was at the door. So it caused me to question how much of the letters were true. There was something emotionally true there. My dad was possessive. She felt trapped. There were certain things I knew hadn’t happened, but I also rushed to my dad’s defense thinking through all the ways to disagree with her, which is interesting too.

BA: You’re entering that space of emotional truth versus factual truth. The emotional truth is not less significant in this moment than the fact that what your mom wrote was not true.

JV: Yeah, exactly. I want to offer two things that might be useful to people reading this. I printed the manuscript, put it in a binder, and I circled certain nouns. I know I can get inside my own head and it could get in a loop, and I needed to break out of that. So I looked for concrete stuff that I could come back to. For example, the newsletter that came with our eggs, Chris’ underwear subscription, the weeds (both literal and metaphorical ones). So when my friend Sarah says, “Oh, it sounds like you’re out of the weeds.” I could go back and circle “weeds” every time they came up. Perfect. I’ll use that as a metaphor. But then the other thing is knowing what not to include. So in the letters, when my mom describes my dad as “evil” and writes “He ruins everything he touches” it derailed the manuscript. And I was like, well, I’ve already written about this. I’m named after a dead half-sister, and I write about that in my first book. My dad’s daughter, Jeanne, died and he blamed himself for her death. His first wife blamed him. And so I thought about how my dad might’ve felt when he read, “He’s ruined everything he touches.” And I got really mad at my mom thinking he went to that place. I don’t know. Originally I had that included. But, oh gosh, this manuscript was getting really cluttered. And also, my dad could overtake the manuscript, and this is for my mom. And so I had to make the decision to leave that out. It’s a matter of deciding what’s a lie of omission and what are you just omitting?

BA: Is that the guiding principle for your curation? Is it intentional that your reader is always catching up to you in the moment?

JV: I’m trying to reproduce the experience. There’s that curated messiness or seeming spontaneity. To introduce too much of that muddied things. I did experiment with including my namesake (my dad’s daughter, Jeanne). But that turned the book into a place where I could end up spending a lot of time on my dad. And this book, this story, is about my relationship with my mom. I was very cautious about how much of him I included.

BA: Earlier you said cause and effect made you uncomfortable. You want it to be messy because it was messy?

JV: I think about that Italian quality of “sprezzatura,” a studied carelessness where you’re trying to make things seem effortless. It goes back to Yeats’ Adam’s Curse: “A line will take us hours maybe; Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought, Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.” We’re making art. It needs to be coherent. But what I like is how Yeats acknowledges how hard it is. I think that goes back to the meta element in A Silent Treatment. That’s keeping me honest, because if this at all seems like it happened in an organized way, then I’ve failed. This was such a disorganized experience, but I don’t want complete chaos. That would be rude to the reader, I think.

BA: When we get to the end of your book, the chaos might be over, but it certainly doesn’t mean, “And then they lived happily ever after.”

JV: Which is why the last chapter is one year later. I couldn’t end this just after a particular silent treatment ends because the reader is going to feel that this will all start again. I thought if I wrote about our relationship one year later it’d give that sense of, “Okay, we’re on the other side.” Things aren’t necessarily better and there isn’t necessarily a happy ending, but something has shifted.

BA: We both teach writing. One of the lessons we give young writers is that the protagonist must undergo some profound change. Yet you write in A Silent Treatment that not every character has to change. Is that more accurate to writing memoir?

JV: The circumstances of a situation may change. That doesn’t necessarily mean you’re going to change. Somebody making a choice who otherwise was not making choices, that’s some degree of change. Even if they go back to being how they were, there is that moment of change. The book used to have a different ending. I got my mom walkie-talkies for Christmas. I thought it would be a fun Christmas gift–it made me think of childhood. And so I had “Mom, can you hear me, over?” Because we were playing with the walkie talkies. I thought “over” was such a good ending. But in practice… it sounds clever, but when I read it back, it felt like I was presenting an ending. It was tacked on.

BA: You promise Chris, “No more memoirs” toward the end of this book. Now you’ve written out about both of your parents and being sexually assaulted as a young woman. Is “No more memoirs” something you imagine holding yourself to?

JV: No! The fourth book is under contract.

BA: Oh! Great!

JV: I told myself I would never write another book like this where it’s under contract but not written. It’s very stressful. But I love my editor. I wanted to keep working with her. I have friends who move away from doing memoir or who go into essays. I find creative nonfiction essays are so hard. I think an essay can take as long as a book to write. And the idea of writing an essay collection; I so admire people who can do that. That just sounds so difficult. You are starting over and each thing is its own world. And I’m like, I just want to work in one world for a book, so I am going to do another.

BA: Thank goodness. We need more from Jeannie Vanasco.